Books that promise clear solutions to the myriad environmental crises the world is facing have their role — sometimes inspiring people to change their diets, or go car-free, or maybe even re-jig their value system away from what was inculcated by capitalism.

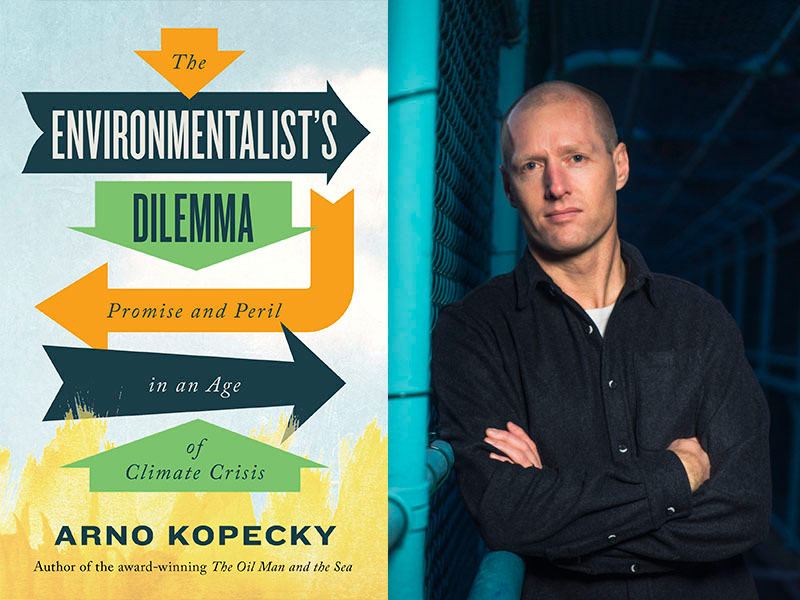

But as the excerpt from Arno Kopecky’s new book The Environmentalist’s Dilemma demonstrates, the act of proffering these solutions has, historically, been thorny business. Western environmentalism is inextricably linked to white supremacy, for example, and if western environmentalism today isn’t actively accounting for those roots and looking to build genuine relationships of solidarity, then the solutions aren’t worth much more than a sandcastle built at low tide.

Instead of offering environmental solutions, The Environmentalist’s Dilemma does what its title suggests: it dives into problems, issues, intersections, complications and dilemmas, navigating through them from Kopecky’s position as a white gen-Xer of German-Canadian descent.

It’s an important task in a world full of complexity, and the book will appeal to anyone whose hope for the future is mixed with an understanding that pursuing environmental justice should mean pursuing other forms of justice, too.

We interviewed Kopecky about the intersections between environmental, social and cultural dilemmas, and why it’s important to tackle things head on, even when there are no easy answers.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The Tyee: A lot of books that tackle environmental crises are positioned to offer solutions: read this, and you’ll learn how to fix this mess we’re in. Your new book is very explicitly about nuance and complexity and mess — dilemmas! Why?

Arno Kopecky: I don’t want to throw any shade at books that do offer solutions. I think solutions are needed and valuable. And those books are crucial.

For me, when you write a book, it usually begins with an impulse, or a sensation, or something that you are drawn to for reasons that you haven’t reasoned through. And for me, that was this messy and complex world historical moment that we’re living through right now.

As somebody who has been writing about environmental issues and climate change for coming on 20 years now, there’s no part of this story that is black and white. Every seeming solution or right way forward involves uncomfortable trade-offs at best. And ultimately, a lot of this stuff comes down to human behaviour and the human condition. You know, the different angels, good and bad, that we have on our shoulders that are at war with one another, from greed and acquisitiveness to empathy and compassion and collaboration, and a search for higher meaning.

With all of this complexity, two ways to respond to it are to say with absolute certainty, “Well, this is the solution, this is the right way forward, listen to me.” And that comes from all sides of the spectrum. And then another way is to retreat into doubt, because there’s so much complexity in the world, and there’s so much information in this media landscape, and there are so many conflicting narratives. It’s easy to sink into fear and doubt and not trust anybody.

My approach is to say, let’s embrace the complexity. Let’s not pretend there are any simple answers, but let’s also not be afraid of nuance and dilemma. Let’s look at those dilemmas head on and let’s see where that can take us. Let’s recognize that there are no perfect solutions. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways forward.

A version of the first chapter of the book, “The Newest Normal,” was published in the Globe and Mail in 2018. It’s a thoughtful essay that aims for an inclusive “us” — a sort of first-person plural flipside of the royal “we,” aiming to speak from your subject position while also including others — while piecing through the question of whether contemporary life is worse now, or better.

I’m curious if the book’s version evolved from the version you initially published, and if some of those differences came about after receiving feedback, or rethinking aspects of the essay? Was it difficult to get to that inclusive “us”? Why aim for an inclusive “us”?

One of the things that I learned about myself in the course of writing this book, and being edited by a wonderful editor, is that I have a tendency to use the royal “we” in my writing. We are adding X amount of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere every year, we are addicted to our iPhones and the internal combustion engine.

My editor was really great at challenging me on that. There’s a long, sordid history in all kinds of literature of white men using that royal “we” to include people in their crimes who are not complicit in those crimes. I’m sure that I have committed that crime to some degree, and not just in the first essay, but throughout the book.

I am not speaking or trying to speak for minority or marginalized communities — queer and trans communities, or Indigenous communities, or people of colour, who come up a lot in this book and who do not face the same world that I do. But at the same time, I think a part of the ethos of this book is that we are, we, all eight billion of us humans, on this planet together. And we are increasingly bound up in the same system of, let’s say, interconnected global capitalism. You can’t really live in this society without contributing to a lot of the issues that I’m talking about. We’re all complicit in it to some degree. And, of course, some are far more complicit than others.

When I say “we,” and “us,” I’m trying to do so in a way that doesn’t squelch individual identities and marginalized communities, who have been squelched and oppressed for centuries, and are just now emerging. But that global community is what I’m trying to reference and encourage.

You seem to have a bit of a love/hate relationship with environmental movements and activism — drawn to them, but not exactly joining. Engaging, but remaining on the periphery. What draws you to them? What makes you hesitant?

Let me start by saying that I believe that almost no major social change or movement in history has succeeded without a strong activist role. Activism is crucial, plays a super valuable role in changing society and getting laws changed, and getting politicians to do the right thing. At a time when it might be hard to do the right thing.

So I’m drawn to that, and I’m drawn to the passion and I’m drawn to anybody who believes in something strongly enough that they’re willing to go out into the streets and risk arrest or worse and just get in there and do it, and give it their free time. I think most activists have a lot of conviction and are trying to make the world a better place and are acting from very good impulses. So that’s what draws me to it.

What sort of scares me a little bit about it is that activism, in order to be successful, has to focus on simplicity and purity. It’s sort of antithetical to nuance. The group that I spent time with was Extinction Rebellion. And their take is that we have to shut down the business of global capitalism right now because the world is collapsing. And I’m very sympathetic to that position.

But their take is, well, governments are not rising to the occasion, so we have to overthrow the government and replace it with a government that is climate and biodiversity friendly. I just can’t help thinking about all the times that governments have been overthrown, and how that usually turns out, which is not positive for the environment, or for the people. And I think about how Canada, for all of its flaws, actually has one of the more representative governments in the history of our species. If you’re talking about overthrowing the government in Canada, I would want to be really careful about doing that.

The other thing that scares me a bit is that near-militant purity and refusal to compromise is almost critical to the success of many activist movements, but it’s also antithetical to the act of writing and of being a journalist. There’s a sort of a fundamental mismatch there between the nuance and complexity that writers are drawn to, and the ingredients that are necessary for success in activism.

I learned towards the end of the year that I spent with Extinction Rebellion that many of them suspected me of being an undercover cop, which was partly hilarious. But also, you know, not that far off. In a way they recognized that I was not necessarily their friend, but I would be honest and critical about them. Not because I’m a cop and I want to arrest them, but because I’m a journalist.

Right after I was finishing the book, people started getting arrested at Fairy Creek. And so I went there and wrote about it for The Tyee. With Fairy Creek, I would draw a bit of a contrast between that movement and Extinction Rebellion, where the goals were very broad and vague. With Fairy Creek, I was really impressed with the specificity and the tenacity. I think it’s been much more effective, partly because their goal is so much more specific. They’re not trying to overhaul global capitalism; they’re just trying to protect a specific area of trees. Which is monumental enough, but it’s a specific goal.

Even there, though, I will say, nuance is sort of antithetical and complexity is antithetical to what they’re doing. If they want to succeed, they can’t spend too much time thinking about the fact that the Pacheedaht Nation’s elected council and Chief have asked them to leave. Versus all the other Indigenous folks, including Elder Bill Jones, and other Pacheedaht members, who are for the protesters and are on their side. If they want to succeed, they just have to stay focused on trees.

Part of the way you engage with the dilemmas you raise in the book is to talk them through with people and share parts of the resulting conversations in the book. For me, a couple of the most meaningful or thoughtful conversations come about when you’re speaking with religious folks — a pastor, a retired Anglican minister. Why, in particular, was it helpful to talk to religious leaders about environmental dilemmas?

I’m not religious myself. But I’ve long been fascinated by what I see as a pretty strong overlap between some of the language of environmentalism, and the imagery of environmentalism, and the language and imagery of religion, specifically Christianity, specifically in biblical imagery.

If you’re talking about climate change, fire and flood sure comes up a lot, as they do in the Bible. And the idea of original sin is pretty compatible with overconsumption and greed. And all the things that they talk about in the Bible are things environmentalism also wrestles with. I don’t think it’s conscious. I think it’s unconscious. But people who have been religious, like the two that you mentioned, the pastor and the minister, they’ve spent their lives thinking about some of these big questions. And coming at it from a very different place, but arriving at some similar meditations, I would say, if not conclusions around, you know, what is our purpose? Where are we going? How do we confront existential crisis?

One thing that really drew me to Harold, the former Anglican minister and Extinction Rebellion organizer, was that he said he was drawn to join that movement because everybody in that movement knows that they are probably going to fail, and that this is probably not going to end well. And yet, they join the cause. And they go for it. He talked about how that can overlay with religious faith in a way — that you do something not because it’s going to give you riches and rewards, but because it is inherently satisfying and inherently the right thing to do.

When you envision the future, do you feel hope for it?

I do feel hope. And I feel fear. In equal measure. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: