The paradoxes of the human species are many, but biologist E.O. Wilson summed it up best when he mused that we are a species with “paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and god-like technology.”

American author Richard Powers makes it even more plain in his new novel, Bewilderment. As one of his character says, “It’s a sad time to be alive.”

The profound alienation we’re suffering comes not only from the ongoing deluge of bad news, but arguably from something deeper: the idea that many of us have forgotten how to exist on the planet. To return to a state of balance with nature, what Powers calls “aligning with the neighbours,” is the novel’s subject.

Bewilderment is Powers’s 13th book, coming on the heels of The Overstory, an epic that won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. How to follow such success is a challenge for any writer, and Powers debated whether he even wanted to write another novel.

But books, like children, often insist on coming into the world whether you’re ready for them or not.

Bewilderment arose out of the author’s experience of writing The Overstory, but it was also inspired by the idea of children as innate natural scientists. Powers says he wanted to “tell a story about a nine-year-old who is absolutely in love with the living world and appalled by what the adults are doing to it, and to connect that story to the geopolitics of the moment we’re living though.”

From this starting point it’s a leap into the cosmos itself, with different sojourns into neurodiversity, biofeedback and the pleasures of drawing animals. Add in a megalomaniac monster running roughshod in the White House, environmental collapse, a virus that has jumped the species barrier and a teenage environmental champion from Sweden, and you might feel like you’ve stepped through the looking glass.

When the story begins, Theo Byrne and his son Robin are still in the raw stages of grief from the accidental death of Aly, Theo’s wife and Robin’s mother. A charismatic firebrand and environmental lobbyist, Aly hovers over the action like a force of nature. If she’s a ghost, she is rather a persistent one, popping up like an undead Greek chorus to offer parenting advice to her still-living husband, who can use all the help he can get.

Robin is an unusual child, described by his father as “sad, singular,” and “in trouble with this world.” The catchall term neurodiverse applies but doesn’t do justice to the particularities of the kid’s character — sweet and maddening, brilliant and helpless.

The world is too much for Robin, who retreats into inchoate rages and violence, unable to cope with the demands of school and other kids as well as his own inner storms. But it is the complacency towards the destruction of the natural world that invokes his most profound anger and incomprehension.

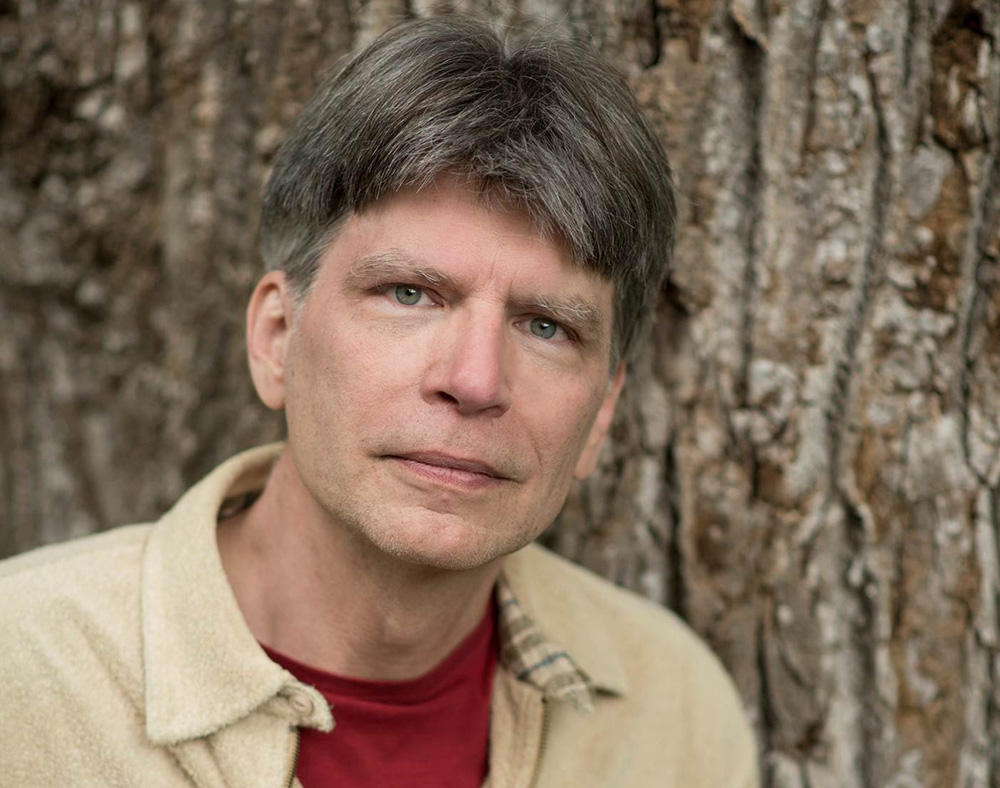

On the phone from Tennessee, where he’s doing press interviews for the book, Powers is soft-spoken and deeply thoughtful, but there is no mistaking the live wire of astonishment and anger that recent global and political events have provoked.

Powers says he didn’t set out to create a “photorealistic depiction of the Trump years,” but rather to capture great crises being played out socially of living on this earth.

Setting the story in the near future, close to the realm of science fiction, allowed Powers room to play. Narrative elements such as technological advancements that don’t quite exist yet, as well as interplanetary exploration, enable a different perspective.

As an astrobiologist, Theo’s job is to search for signs of life in the universe in the furthest tangles of the stars. Back on planet Earth, however, things aren’t looking so good. After assaulting another child, Robin is suspended from school and threatened with a pharmaceutical regime to quell his anger.

In an effort to soothe his son’s agony, Theo spins interplanetary travelogues, using planets as bedtime stories. On these other imagined worlds, all manner of different kinds of life unfold.

Powers believes that the search for other forms of life is driven by the human need to not be alone. “Our desire to know the cosmos is as old as we are,” he says. “Theo’s job didn’t even exist a while ago, when we were told we’d never see direct evidence. Now there are a thousand catalogued planets. Are we a fluke, or does the universe want life?”

It’s an idea that finds expression not only in science fiction but also in concepts like the Fermi Paradox, which takes its name from physicist Enrico Fermi who asked, plaintively, if there were other forms of intelligent life in the universe, why haven’t we heard from them? Of this great silence, he said: “Where is everyone?”

The question permeates Bewilderment. But instead of searching the heavens, we might do better to simply look around us. As Robin states in the book, if humans can’t see that dinosaurs are still with us in the form of birds, what hope do we have in recognizing and valuing other life forms, like trees, that might not bear the faintest similarity to homo sapiens?

Powers based one of his characters in his previous novel The Overstory on Suzanne Simard, immersing himself in her work on the communication strategies of forests. After finishing The Overstory, he made a commitment to include non-human characters in his future work, with the intent of disrupting our ongoing, near inescapable solipsism.

This form of literary bias — that people are only interested in stories about other people — Powers views as being leftover from earlier forms of literary drama. Humans against the world: Jack London, Herman Melville–type stuff, wherein we thought we’d “won” the “war” against nature.

Powers’s commitment in Bewilderment to decentring humans involves not only animals and plants but also other beings from distant planets. It’s a reminder that despite human hubris, we’ve only dipped the tiniest of pinky toes into the vastness of the universe.

The novel’s quest is to discover whether we’re a one-off, or if life is everywhere — beginning at home, with the ongoing work that is family, love and grief. “Pain and beauty are very close together,” Powers tells me. “It’s the awareness of mortality that allows us to feel beauty more intensely.”

As much as Bewilderment is a book about the processes of human suffering, it also contends with sorrow of the planetary kind, as mass extinction looms, environmental breakdown barrels along and anti-science forces rule the roost.

“I cannot be hopeful for the present,” Powers says. “We can’t continue to live this way, but the ending of the culture we’ve created is not the end of hope.”

Bewilderment asks a fundamental question: What does life need? For Powers, a commitment to engage with the future offers the joy and rewards of a rehabilitated planet, an end to the separation from life, and a means to address our deep and abiding loneliness.

The job of artists and writers is to summon possible futures that have never been imagined before. Powers is part of this envisioning.

“Books are themselves empathy machines,” he says, “capable of opening the locked box, if only briefly to be someone other than ourselves.”

Bewilderment’s star-shined convergence of fact and fiction, narrative and emotion leaves one reeling, dizzy and destabilized, caught in the momentary out-of-body state that only a great novel can induce. In this state hovers the possibility of living differently.

In kinship and communion with other living things, be they frogs, forests, rivers or the unseen universe of mycelium, we find ourselves. Bewilderment brings home what Powers calls “a sense of our of own endless good fortune.” That in spite of everything we’ve done to it, the Earth endures. ![]()

Read more: Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: