[Editor’s note: ‘The Ocean’s Whistleblower’ tells the story of Daniel Pauly, a living legend in the world of marine biology. The new book by David Grémillet is part coming of age story — Pauly was born in post-war France to a white French woman and an African-American G.I. — and part deep dive into the challenges of marine research. Excerpted below, a section of the book relating how Pauly took his field of science to a new level.

On Tuesday, Sept. 28 at 7 p.m. PDT, The Tyee will present free of charge, in partnership with Upstart & Crow, a conversation between Daniel Pauly and Ian Gill. The event will be online, and tickets are available through Eventbrite.]

“In the late '90s, people were realizing that fishing is actually a problem for the oceans,” says Daniel Pauly. “To figure out if this activity is in the process of wiping itself out, you have to go beyond the Bay of Whatchamacallit or the Gulf of Whatever. When astrophysicists can’t see something well enough, they build a bigger telescope. So that’s what I did, build a bigger machine, the biggest one I could imagine — the world since 1950.”

Pauly had played instrumental roles in the development of both Ecopath, an open-source ecosystem modelling program, and FishBase. a global fish species database. With these two tools at his disposal, he now had all he needed to study fisheries on a planetary scale over a period of several decades.

But Pauly also needed lots of data to feed those tools, which ran on information laboriously gleaned from the scientific literature, and his resources in Vancouver were limited. He applied for funding from the Canadian government several times without much success. “I stopped asking them the day I received a response that said my application was excellent, but they still couldn’t give me any funding,” he says. Initially, therefore, he had to rely on his students at the University of British Columbia and his colleagues at the International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management.

After studying the problem of trophic levels — the position any given species occupies in a food web — during the development of Ecopath and then again for his first article in Nature with Villy Christensen, Pauly realized that he could calculate the mean trophic level of all the fish caught in a particular zone over a certain period of time. For example, if a fishery mostly caught tuna, swordfish and other superpredators, the mean trophic level would be higher than if it mainly targeted small vegetarian fish like anchoveta.

As an exercise, he asked his master’s student Johanne Dalsgaard to run such a calculation for the catches of all the fisheries in the northeastern Atlantic from 1950 to 1994. Dalsgaard based her work on the Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations’s fisheries statistics, which tracks catches according to species group, and the trophic levels of each of these groups, calculated using a series of Ecopath models. She found that the mean trophic level declined over time, which indicated that European fisheries catches were increasingly composed of fishes from the lower part of marine food webs.

The results didn’t come as a big surprise to Pauly, who knew that despite the best efforts of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, the northeastern Atlantic was still overfished, causing larger species to decline and forcing fisheries to fall back on smaller fish. These smaller targets initially multiply because the fisheries have eliminated their natural predators, but their stocks are soon overexploited in turn.

Pauly had nearly forgotten about this analysis when, several weeks later, he found himself at the Singapura restaurant in Manila with Villy Christensen and Rainer Froese. He was eating low-trophic-level Sambal squids with rice.

“What happened is that I suddenly realized that the plot by Johanne Dalsgaard could be easily expanded to cover the whole world,” Pauly says.

Christensen and Froese were up for the challenge, and the team got to work with the help of Francisco Torres, who assigned a trophic level to each of the 1,200 species cited by the FAO, a task he politely characterizes as “tedious.” A few turns of the data mill later, they had their verdict: the trophic level of organisms fished in both salt and fresh water had declined since 1950 all over the world.

The paper where they presented their analysis “literally wrote itself,” according to Pauly. He sent it to Science, the ultra-selective American journal. Their four-page contribution received a positive evaluation and appeared in 1998 with the title “Fishing Down Marine Food Webs.”

Pauly and his colleagues emphasize that, despite this general trend, they also detected important regional variations, the drop in mean trophic level over time being stronger in the northern hemisphere where the fisheries are more highly “developed.” They go on to underline the fact that “present exploitation patterns are unsustainable” and bring their article to a close with the following recommendation: “in the next decades fisheries management will have to emphasize the rebuilding of fish populations… within large ‘no-take’ marine protected areas.”

The article appeared in Science with the headline, “What is the future for fisheries worldwide? Bleak, according to an analysis by Pauly et al.” An editorial accompanied the paper relaying the reactions of fisheries specialists, one of whom called it “a wake-up call.”

The text ends with a short remark from Pauly, one of those zingers for which journalists would come to love him: “If things go unchecked, we might end up with a marine junkyard dominated by plankton.”

Pauly, who already had a solid reputation in his field, became a celebrity thanks to that article, which is still the one he is best known for today.

I discovered the article at the library of the oceanographic institute in Kiel in February of 1998. “This guy is good,” I thought to myself. “He’s used open-source data from the FAO to do analyses that are simple yet revolutionary, and he’s shown the world that everything marine ecologists have feared to be true for a long time is really happening.”

His conclusions reminded me of a book I had read recently in which — already, in 1984 — Timothy Parsons and his colleagues had announced that “no form of marine pollution is in any way comparable to the ecological impact which occurs with the removal of circa 70 million metric tons per year of predatory fish from the ocean ecosystem.” These words impressed me so much that I copied them down and pinned them to my dorm room wall.

The paper in Science was picked up by dozens of news outlets around the world but didn’t make much of a splash in Pauly’s native France. Still, he could hardly suppress his pride when the New York Times, which he read religiously, published a long article on his work in the science section. Aside the fact the Times journalist misidentified him as “David” Pauly, he found the piece to be “accurate, informative and well-written.” In particular, the article explains that, according to Pauly, marine food webs will be “collapsing in on themselves” within 30 or 40 years if nothing is done.

The term “collapse,” referring to both social and ecological contexts, appeared in that article years before the publication of Jared Diamond’s book bearing that title.

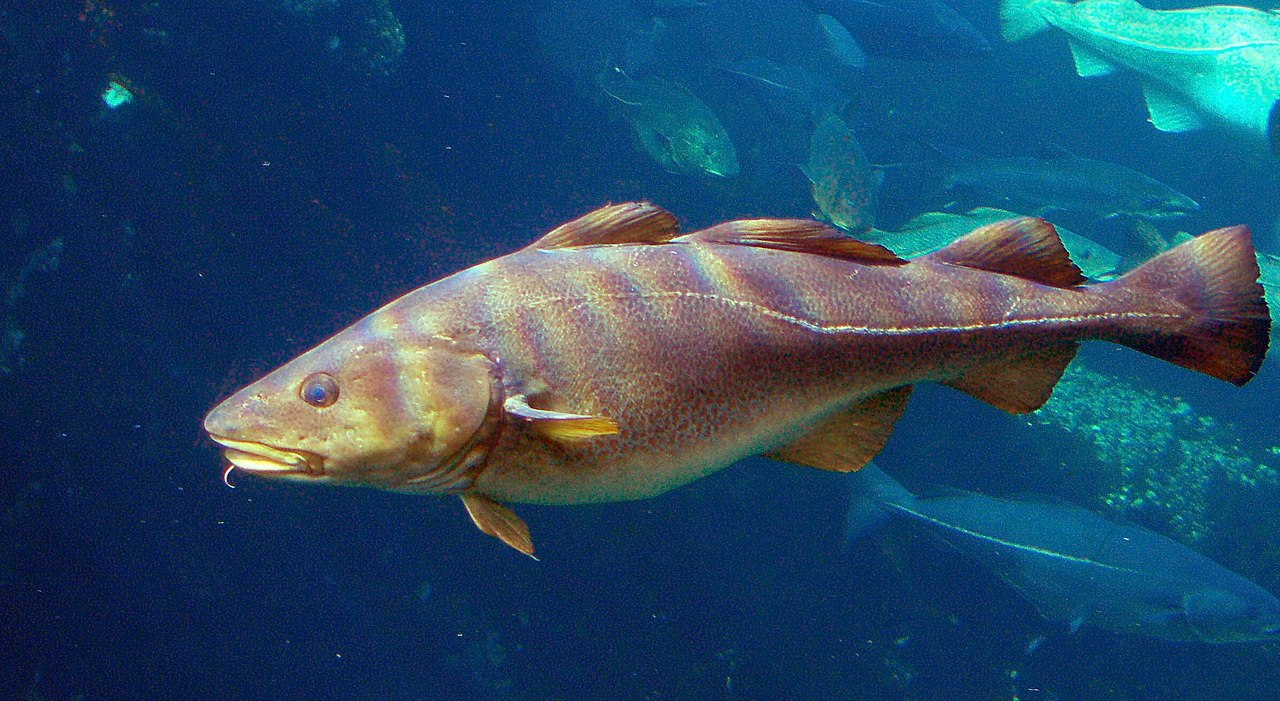

To illustrate his point, Pauly tells the old story of the Newfoundland cod, pointing out that after that fishery was closed, the bottom scrapers known as trawlers shifted their attention to the cod’s prey, shrimp. Once this new resource has been plundered, will fishers go after the shrimps’ prey? Hard to do, since they mostly eat detritus.

“It’s mud,” quips Pauly, concluding, “That’s when you hit the wall beyond which the fishery has no more commercial value.”

Excerpted from ‘The Ocean’s Whistleblower: The Remarkable Life and Work of Daniel Pauly’ by David Grémillet. Copyright © 2021 David Grémillet. Published by Greystone Books. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: