Brian Owens’s new book, Lyme Disease in Canada, published by Formac, tracks the discovery of the disease here, and its rapid geographic expansion due to climate change. At The Tyee we know he’s a stellar science writer because he writes the COVID-19 science journal roundup that runs every Tuesday.

Tomorrow, we will be running an excerpt from Lyme Disease in Canada that explores why the first vaccine, which was available from the late ’90s to the early 2000s, met with resistance and an eventual removal from the market.

Today, we grill Owens on all things ticks and Lyme — including medical skepticism, Lyme disease prevention and the most surprising information he learned while researching for the book.

The Tyee: What is Lyme disease? Why was there skepticism in the medical community about Lyme disease, initially?

Brian Owens: Lyme disease is an infectious disease caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi, which is spread through the bites of ticks, particularly the blacklegged tick. It has a wide array of symptoms, including fever, headache, joint and muscle pains, fatigue and sometimes a red, bull’s-eye-shaped rash. If left untreated it can develop into chronic or recurring arthritis, neurological symptoms like problems with memory or cognition, and in rare cases dangerous heart conditions.

Though Lyme disease was first discovered by doctors more than 40 years ago, many doctors in Canada didn’t know much about it, or didn’t accept that it was present here, until fairly recently. For a long time it was thought that the only place you could get Lyme disease in Canada was in one small spot in southern Ontario. But now we know that it is present in every province, and that there is really nowhere in the country where the risk is zero.

If you get bitten by a tick, how likely is it that you’ll get Lyme disease? And if you do get it, how treatable is it? Is it curable?

The most recent studies have found that roughly 30 per cent of blacklegged ticks carry the Lyme bacteria — though that number is likely somewhat lower in B.C. because the western blacklegged tick does not seem to be as good a host as its eastern relative. If you are bitten but spot and remove the tick quickly, before it starts to feed, your chances of catching the disease are low because it takes some time for the bacteria in the tick to wake up and move to its new host. The usual rule of thumb is that a tick needs to be attached for 24 to 48 hours before the bacteria can move on, but that is not a hard and fast rule — the bacteria isn’t checking the clock — so it could happen more quickly under some circumstances.

If the infection is caught early and treated promptly with antibiotics, most people will recover fairly quickly. But the longer the infection goes unnoticed, the harder it is to treat. And some people, perhaps as many as one-third of those infected, continue suffering from the symptoms even after treatment. This is often called “chronic Lyme disease,” but what causes it, and how it is best treated, remains something of a mystery. And many doctors continue to doubt that it is a real illness at all. So the best strategy is to take precautions to avoid being bitten in the first place.

Your book begins with a quote from journalist Mary Beth Pfeiffer: Lyme disease is the “first epidemic of climate change.” Could you explain what Pfeiffer means by this?

Cases of Lyme disease are increasing rapidly, in both numbers and the areas affected, as the climate warms. A warmer climate in Canada, especially milder winters, allows more of the ticks that carry the bacteria to survive the winter and to expand their range northwards to places where they couldn’t survive before. And it’s happening fast — scientists from the Public Health Agency of Canada found that tick populations are moving north at a rate of 30 kilometres a year.

Are doctors now more open to considering Lyme disease when patients come forward with symptoms?

It is now generally more accepted that Lyme disease has become endemic in many parts of Canada, so doctors are more likely to consider it when the symptoms appear. But it can still be difficult to get a diagnosis if the patient doesn’t have the bull’s-eye rash or doesn’t remember a specific tick bite. The diagnostic tests used in Canada are also not completely reliable, but many doctors will not diagnose the disease without a positive test. But while doctors probably have too much faith in the tests, the “Lyme warrior” patient advocates probably have too little — they’re not perfect, but neither are they completely useless. They just need to be one of several factors that feed into a physician’s clinical judgement.

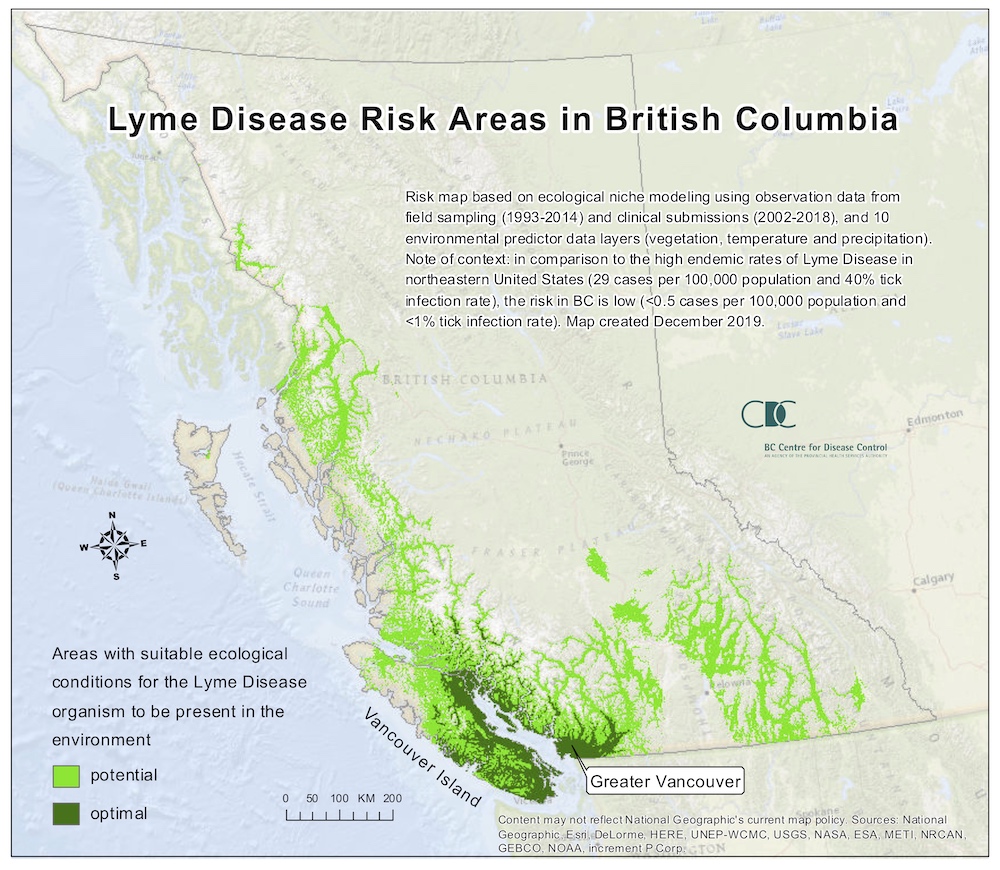

In B.C., the government seems hesitant to recognize Lyme as a provincewide concern. Do you think maps like the one above sourced here are a valuable tool to help people gauge their risk? Or do they give people a false sense of security?

That map is generally a good indication of where the risk is highest in the province — along the coast and up river valleys in the Interior. Ticks particularly like the edge of forests where there is lots of moist leaf litter on the ground for them to hide in at night. If it’s too cold and dry, they won’t last long. But people should be aware that nowhere is going to be completely safe. While the habitat may not be suitable for ticks in the other parts of that map, they can still end up there by hitching a ride on migrating animals and birds. They probably won’t be able to establish a permanent population, but they can hang around for a while and bite anyone who passes by.

There are also other kinds of ticks that live all throughout the province. And while they generally don’t carry Lyme disease, there are any number of other tick-borne illnesses that you need to be careful of as well.

What steps should people be taking to protect themselves?

When you’re out in tick habitat there are many things you can do to protect yourself. Wear light-coloured clothing so the ticks are easier to spot. Use an insect repellent like Deet, or clothing infused with permethrin, and tuck your pants into your socks, fashion be damned. When you get home, check yourself carefully for ticks — or better yet, get someone else to do it. Pay close attention to all your nooks and crannies, as ticks particularly like to nestle into places like your groin, armpits and hair. Ticks are tiny before they start to feed: nymphs are just the size of a poppy seed and adults are the size of a sesame seed. So when you do your tick check, be on the lookout for freckles with legs.

What’s the most shocking thing you learned about Lyme, or ticks, while researching Lyme Disease in Canada?

I was surprised to learn the story of the failed Lyme disease vaccine, especially given how quickly and successfully we were able to develop multiple different vaccines for COVID-19. More than 20 years ago we had an effective and reasonably popular vaccine for Lyme, but it was taken off the market mainly due to bad press — it came out just as the modern anti-vaccine movement was gaining steam around the false and fraudulent link between the MMR shot and autism, and similar concerns were raised that the Lyme vaccine could cause arthritis. It turned out not to be true, but the company decided that the controversy and lawsuits weren’t worth it, and pulled the vaccine from the market. Now you can get your dog immunized against Lyme, but not yourself. There is some hope though — a French company is testing a new vaccine now, and hope to bring it to market within the next few years. ![]()

Read more: Health, Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: