Before I moved to Tiskwat, B.C. (currently known as Powell River), with my partner, kid and cat in early 2019, I studied real estate prices — we needed somewhere affordable — and tsunami maps. I come from a prodigious line of worrywarts and have long been drawn to writing about disaster.

But it wasn’t until heartbreaking videos of the fast-moving fire in Lytton, B.C., began emerging — mostly filmed by people from their cars, as they escaped — that I began to think (panic?) about how our communities account for low-income, car-less and disabled people during emergency evacuations.

PreparedBC recommends that everyone living in the province develops an emergency plan, an emergency shelter-in-place kit and a grab-and-go bag.

The kit is supposed to contain enough water and food to last your family, including pets, for a minimum of three days — longer, if you live in a more remote area.

“We know from Vancouver Island, that the whole island has a roughly three-day supply of food,” says Ryan Reynolds, a postdoctoral research fellow at the School of Community and Regional Planning at the University of British Columbia. “So having your own is going to be critical.”

If Vancouver Island — or ferry-access-only mainland towns like mine — experience an earthquake or tsunami that limits ferry and barge access, Reynolds says, local stores may become depleted quickly, so people should aim to have something more like a two-week supply of non-perishable food and water available.

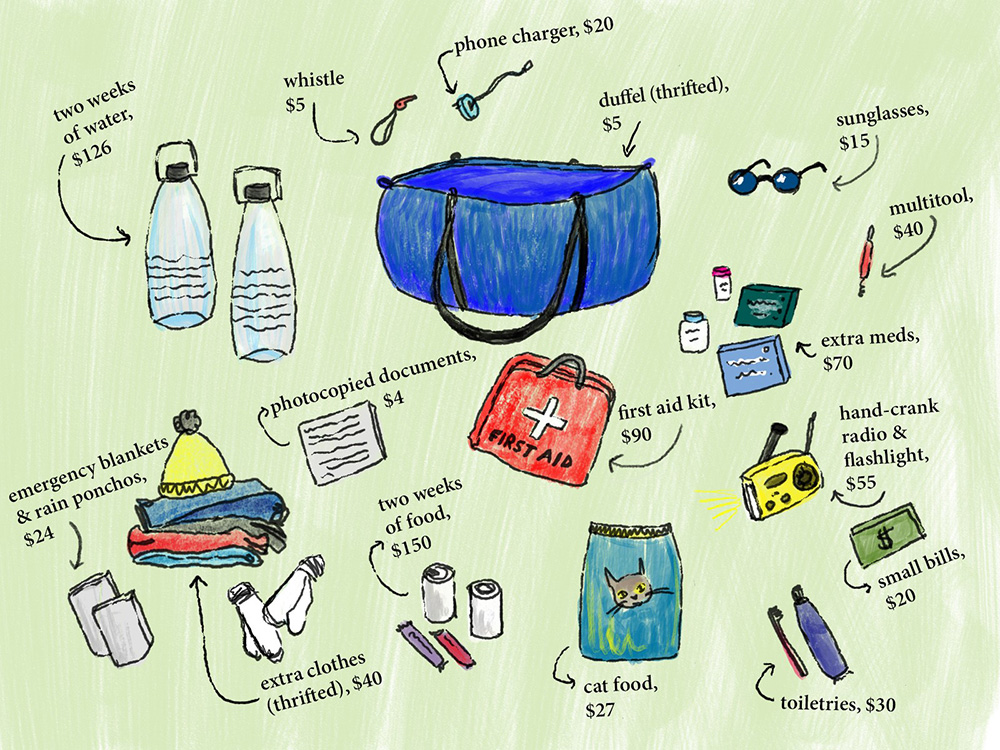

Emergency kits should also include a battery-powered or hand-crank radio and flashlight, personal toiletries like toothbrushes, soap and tampons, dust masks if you live in an earthquake-prone area, a whistle, seasonal clothing, copies of important documents, garbage bags, and a first aid kit that includes a stash of your regular and emergency medication.

While PreparedBC does have tips for developing a kit on a budget — get your emergency rations on sale at the grocery store, use old electronic equipment, buy seasonal clothing on the cheap from a thrift store — this advice can only go so far.

As I’ve assembled my household’s emergency kit over the past couple weeks, I’ve costed it out. And it’s expensive!

The running total for my emergency kit, which will double (sans some of its food and water) as a grab-and-go bag, is $721. This includes some items that are personally specific, like migraine medication, sunglasses (to avoid getting migraines) and antihistamines. PreparedBC recommends that disabled British Columbians keep spares of mobility aids, communication aids and medical supplies in their kits — which could quickly become prohibitively expensive, especially given that over a quarter of Canadians whose disabilities prevent them from working live in poverty.

If my family needs to shelter in place, we’ll be able to use our whole kit. If we need to flee, however, we’ll be fleeing, as a car-less (or “car-free”) family, by bicycle or canoe. The three-day supply of water we’d need to carry would weigh 36 kilograms, or just under 80 pounds — heavy, and potentially too voluminous to fit onto our bike trailer with our cat carrier and other necessities.

I asked Reynolds about how the province and municipalities were accounting for low-income, car-less and disabled people in their emergency planning — to me, its messaging appeared to focus on middle-class families with access to disposable income and vehicles.

“You’re not wrong,” Reynolds says. “The messaging tends to be for the family with two kids and a dog, and one or two cars. That’s pretty much the standard messaging that you see from federal, provincial, even local government services.”

In Port Alberni, where the geography makes the community susceptible to tsunamis, Reynolds says the city has planned to divert public transport buses to the tsunami zone to pick up anyone who isn’t able to use their own vehicles to evacuate.

“The problem is none of that operates after a certain time, like 8 o’clock or 9 o’clock at night,” Reynolds says.

“I think that the feeling is it’s irresponsible for us to have bus drivers or taxi drivers drive into a danger zone to pick people up and leave. I think that’s probably fair. But it does mean that that onus is on friends, neighbours and relatives to assist people that don’t have cars,” he adds.

Jessie Macdonald, an evacuation planning assistant with qathet Regional District, where I live, says the first step for car-less people in our community should be to talk with our neighbours. If there’s an emergency, she says, it’s a great idea to have a plan in place to hop in someone else’s car.

“If there are a number of individuals with mobility challenges or without a vehicle that need assistance, the emergency operations centre within the local authority would co-ordinate transportation resources for those individuals, whether that’s city buses or buses provided through other resources,” Macdonald adds.

Qathet Regional District provides eight location community evacuation guides, broken down by geographic region, that outline evacuation routes, local emergency services and community centres or facilities that can act as meet-up and resource sites in the event of emergency.

Four of these sites include sea cans packed with emergency resources like food and blankets; the district has just received funding from the Union of BC Municipalities to purchase and fill a fifth.

Beyond monetary barriers and evacuation concerns, B.C.’s messaging around stocking up on medications, for example, also doesn’t suit everyone.

Anyone whose prescription is tightly controlled, as is the case for some painkillers, ADHD medication and methadone, or whose prescription requires refrigeration, such as insulin, will find it tricky to keep a two-week supply on hand. Added to that, BC’s PharmaCare program generally only covers a prescription if you have less than 14 days’ worth of the medication left.

Reynolds says that strategies for addressing this issue will vary from province to province, and community to community.

“I have heard of pharmacies being opened up or even doctor’s offices being opened up to get samples in some emergency cases,” he says. “That is a community-level piece, where community leaders or emergency managers have to connect with those pharmacies, doctors, hospitals, whatever it is to make that as part of their community plan.”

“But I have not heard of massive issues in the past,” he adds. “The one that comes to mind is diabetics. It’s critical to get insulin, and it’s kind of hard to keep a two-week supply of insulin just because it’s so perishable. But there are mechanisms out there to do that.”

In qathet, Macdonald recommends that anyone on restricted medications, or medications that need to be kept refrigerated, develop a personal plan in the case of emergency.

“We recommend that individuals that do have special considerations for their medications speak with their pharmacy, and keep that medication information available in their grab-and-go bag,” says Macdonald. “So that if they need to receive that medication from another pharmacy, or it needs to be sent here from a different location, that they have their prescription, and if it can’t be sourced locally, that it can be brought in from an adjacent community.”

Macdonald also stresses the necessity of neighbourhood-level plans. Knowing your neighbours, and pooling your resources, she says, is a key step of emergency planning. If someone has a generator, for example, you can make a plan to refrigerate your insulin.

In qathet, the community provides a neighbourhood preparedness guide outlining what resources people should be thinking about sharing. The city is also currently providing grants for block parties — a great opportunity to corner your neighbour while they’re barbecuing in order to ask them if they happen to own a generator, or chainsaw.

Macdonald also recommends people in our area sign up for the qathet region’s community notification system, which will disseminate information about emergencies and evacuations. She’s available, she says, to help anyone who needs a hand registering.

We all need, she says, to be aware of our local hazards, to be prepared, and to know what resources we’ll be able to access — and to share.

“I think COVID has really exemplified how important community is and our relationships within the community are,” Macdonald says.

“In an emergency, it’s so key to be able to connect with others and not feel alone.” ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Municipal Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: