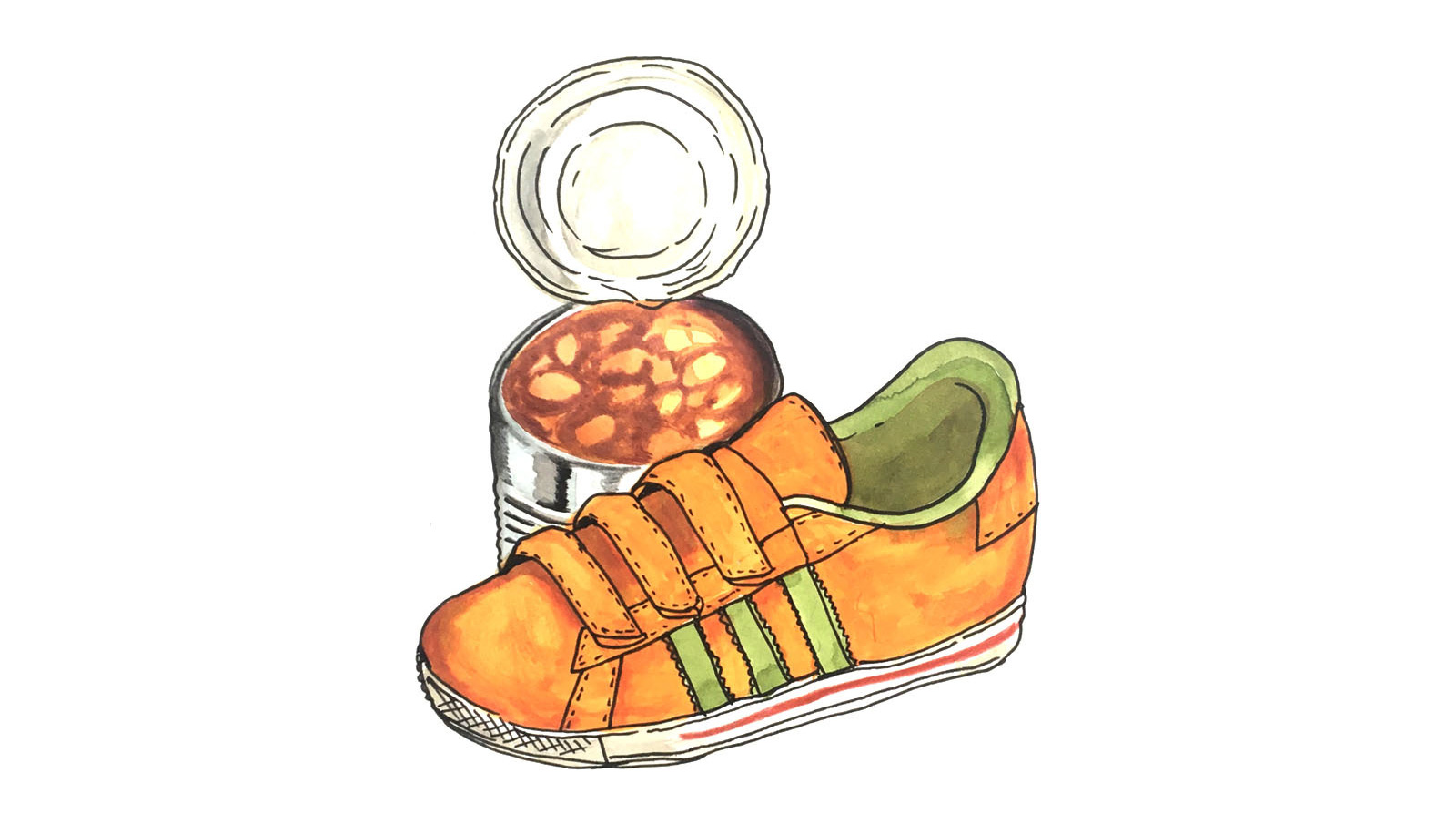

Who is Bean Dad, and why does everyone hate him? In short, the story concerns a father, his hungry nine-year-old daughter, and a can of beans.

As recounted by the father (a self-described “apocalypse dad”) on Twitter, the girl wanted a meal, but dad refused to help open the can, challenging the girl to figure it out for herself. A six-hour struggle ensued, filled with childish tears, paternalism and finally… victory. Of sorts.

The story elicited alternating waves of condemnation and applause. Opinion, as is the way these days, was sharply divided. One camp saw the incident as a teachable moment, an opportunity to pass along the gifts of self-reliance, independence and beans on toast. Others viewed it as borderline child abuse and neglect.

Is there any greater dread, though, than worrying your child won’t grow up to be competent in this harsh old world? I once felt it so deeply I wrote an article about my son for The Tyee entitled Generation Velcro. Today, twelve years later, I offer you — and Bean Dad — an update.

The story was prompted by a trip to the shoe store with my son Louis, seven years old at the time. What started as an ordinary errand turned into a social awakening of sorts, when a clerk at the store held forth about children failing to learn how to tie their shoelaces.

The gist of his speech was that an overreliance on Velcro had deprived an entire generation of basic life skills. Dark days lay ahead as the human race tripped on untied laces and spiralled headlong into learned helplessness.

After getting shoe shamed, Louis and I slunk away with a pair of lace up sneakers, determined to break the cycle of lost knowledge.

But that wasn’t quite the end of it. After a CBC interview, the essay was excerpted in a university textbook, and every fall, when students troop back to school, it pops back up again in internet searches.

When I read about Bean Dad, shades of the Velcro incident reoccurred.

Finding the right balance between independence and caregiving for parents and kids is complicated. A little hardship and struggle are useful, but too much and be prepared to pay for therapy. Most parents struggle gamely along, trying to allow their children to discover their limits while still keeping the little buggers alive.

Layered into this is the ongoing battle of the generations. You know the drill. “Back in my day, we had to hike 30 miles to school, in a blizzard, while fending off random cougar and bear attacks.” The implication being that kids these days — soft, ill-prepared, and unable to fight bears with their tiny hands — aren’t capable of contending with the challenges of ordinary life.

Given the ongoing consternation, it seemed like a good time to revisit Generation Velcro and see how things turned out.

I have good news and bad.

The good news is that Louis learned to tie his shoes, as well as a number of other things. After coming home early from university in December due to COVID-19, he reorganized our entire apartment, installed a knife rack, put up shelving, replaced the weather stripping, cooked dinner, did laundry, bought groceries, balanced a budget, worked part-time and took online courses.

Now the bad news. He’s actually better at a lot of these things than I am, and he likes to tell me so.

How the other Velcro shoe has dropped.

Far from being helpless little wiener babies, it turns out that generation Z, the kids raised on Velcro and video games, are actually pretty good at getting stuff done and fending for themselves. There are some obvious examples like climate activist Greta Thunberg or teenage inventor Gitanjali Rao.

But it’s the ordinary, less world-shaking examples that give me the most hope. Not just the big things like ending racism, sexism and global warming, but smaller things like putting together Ikea furniture, making an excellent stir fry and separating the laundry.

How they came by all this knowledge isn’t exactly clear. I don’t think it was from listening to their parents. God knows I never paid much attention to anything my parents ever said.

Maybe it’s the parents that are the problem. The Bean Dad story is emblematic. Once the internet turned its great lidless eye upon the family, Beanie’s history of problematic tweets came quickly to light, and he was forced to issue an apology. As many critics have pointed out about the story, kids asking for help shouldn’t be a shameful thing, and independence must be balanced by shared responsibility and compassion.

In all likelihood, this will be the end of Bean Dad’s story — unless the daughter grows up, becomes a master of bean cuisine, and starts a global chain of legume-based restaurants before consigning her father to a home. I guess that means I can look forward to the day when Louis writes a tell-all story about his evil mother and her obsession with tying knots.

At the core of the Bean incident is the fear that children won’t be able to cope without our help and support, but also that basic skills, once vanished, are difficult if not impossible to regain.

I once thought this as well. The Generation Velcro article included a bit of doom-mongering about the loss of knowledge, predicted by Jane Jacobs in her seminal work Dark Age Ahead.

But Jacobs and I were both wrong. One of the stranger gifts of the recent pandemical period was people, parents and children, rediscovering and relearning ordinary abilities, whether that was baking bread, darning socks or propping up democracy.

If you have to figure something out in order to feed yourself or protect your loved ones, it turns out that you do it. All that was missing before was the ingredient of necessity, as well as the addition of time.

In my original article, I cited Torkel Klingberg’s The Overflowing Brain. Klingberg, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute wrote, “If we do not focus our attention on something, we will not remember it.”

Well, there’s nothing quite like a months-long lockdown to focus one’s attention. Without the constant busyness of getting and spending, mastering all kinds of activities and skills became something of a cultural obsession.

But there’s more to it than that. The ability to build, fix, mend and make carries with it a great deal of pleasure and satisfaction. Rediscovering this was an unexpected boon in a dark time. Once you learn how to do stuff yourself, there is no going back again to reliance on others.

Here is where the Velcro story comes full circle. To that long-ago shoe store clerk, the efficiency of Velcro straps meant a repudiation of the harder and more fumbly work of tying laces. But it turns out that he, too, was wrong. You can have both.

Kids born into the internet era are able to process information in virtual environments with dazzling aplomb, but this hasn’t precluded them figuring stuff out in the real world. They can master both with equal facility and competence.

In other words, they can fix your router, build digital worlds, and bake a cherry pie, all pretty much simultaneously. This ability to manage multiple tasks and process different streams of information with fluid ease has always bowled me over, and now it’s been joined by other skills.

People who came of age during world-changing events like the Great Depression never lost the habits honed during that time: qualities like thriftiness, creative problem solving, and a dedication to making do. It makes me wonder what habits will be forged in this particular moment.

As much as Bean Dad sounded like a jerk, I have some sympathy for the man. The saga released strange echoes of Louis struggling with his laces, wailing that he couldn’t do it, and me, his harried, cranky mother yelling back, “You need to learn to do this yourself! You can’t depend on anyone to do it for you!”

Except that now the tables are turned.

As the pandemic lockdowns continue to make even the most ordinary activities a struggle, I worry about Louis heading back out into an unsafe and uncertain world. But he’s determined to return to university and a measure of independence.

This time, it’s me saying, “Just stay a little longer. Let me help you.”

But as he says, “I’ll figure it out. I always do.” ![]()

Read more: Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: