It is one thing to see a painting in reproduction, on a screen or in a textbook. It’s quite another to see it in the flesh, up close and personal. Cree artist Kent Monkman’s epic paintings demand to be seen.

Monkman is perhaps most familiar for his recent ruckus-causing work that depicted Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in a compromised position, but his body of work is just that — a body. It is physical, visceral stuff that challenges viewers on an almost cellular level.

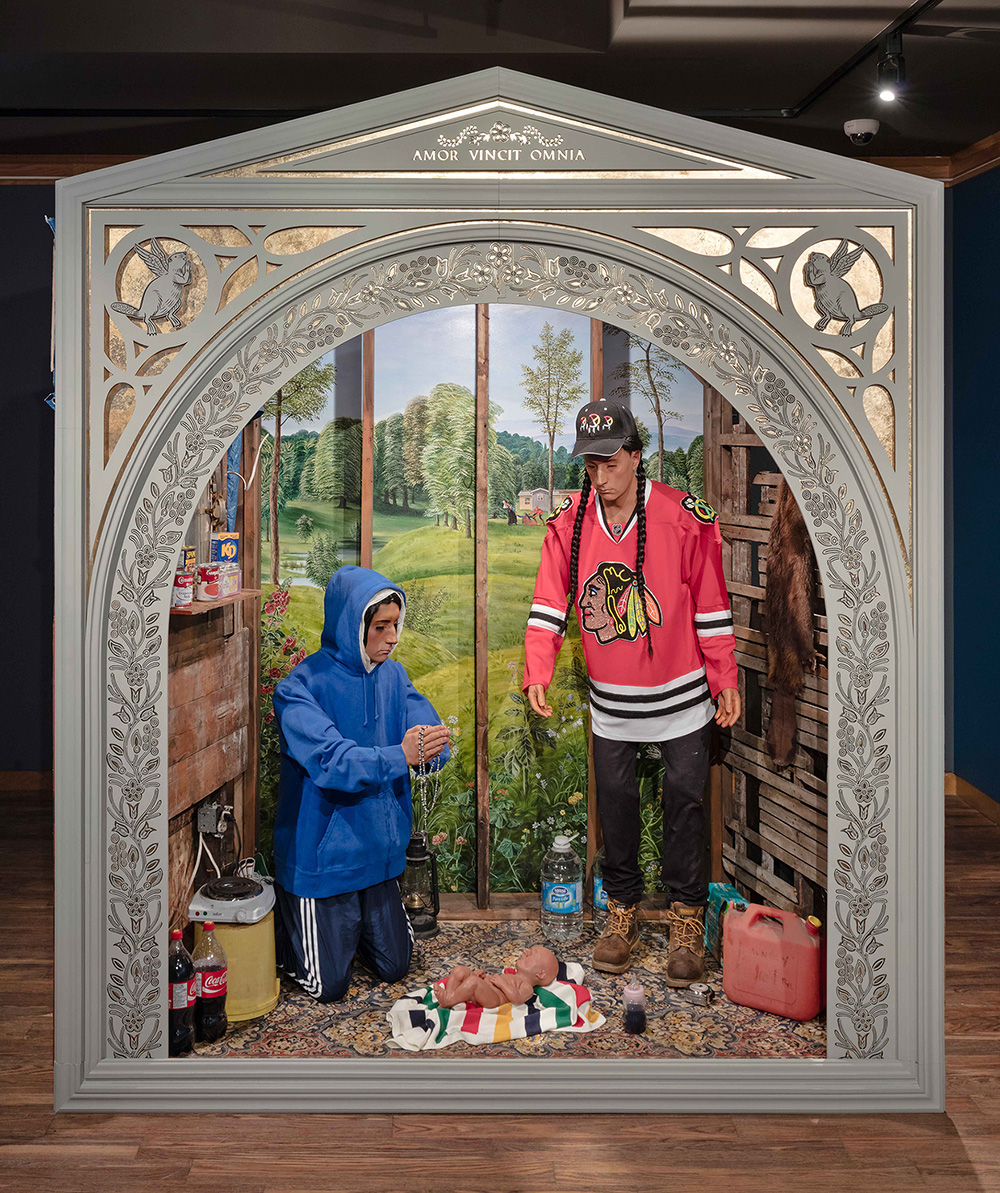

The Museum of Anthropology at UBC’s major new exhibition, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, features Monkman’s paintings and installations alongside items the artist curated from collections and galleries across the country.

In the monograph that accompanies the show, printed in both Cree and English, Monkman dates the genesis for his history paintings to a singular experience with a work by Spanish painter Antonio Gisbert titled The Execution of Torrijos and his Companions at Málaga Beach (1888). It’s clear why the work had such an impact on Monkman.

The depiction of a massacre packs a considerable wallop, not only in its subject matter, but also in the composition itself. It is luminously beautiful, pellucid even, in its depiction of wholesale slaughter.

As Monkman says of Gisbert’s masterwork: “The scale of it, the composition, the level of restraint. The small gestures, hands, faces, expressions and the fact that it’s 14 feet tall! It envelops you.”

There is something of this same aspect in Monkman’s work, a curious juxtaposition of horror and beauty that destabilizes as much as it compels.

The idea that classical painting has the power to leap lightly across hundreds of years and pierce a person to the core affirmed for Monkman that painting was how he wanted to create an impact. It set him off in a new direction, he explains.

Although he’s worked in other mediums like performance and film, “painting is still my root practice,” he says. The rest of his work “all serves painting.”

The MOA exhibition, running until January, is the last stop of the exhibition’s tour. When Shame and Prejudice first opened at the University of Toronto in 2017 the world was a different place.

The show started as a response to Canada’s 150th anniversary celebrations. But in the three years since its launch, there’s been an ongoing reassessment of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous people. The cultural landscape has also changed profoundly in the wider world, with #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and a global pandemic opening up dialogue in radical new ways.

As an artist, Monkman has been hard at work for years, provoking conversation and engagement with Indigenous issues in a deeply personal way. As he writes in the foreword to the exhibit guide:

“As I began to assemble this exhibition, I reflected on the impacts of the residential school system in my own family: the removal of children, the cyclical violence and abuse handed down from one generation to the next, the loss of our language and cultural knowledge, the impact of the Church, the destruction of addiction, and incarceration, if all of this was present in my own family, the impact of colonization on Indigenous families and communities is statistically so staggering it’s nearly impossible to comprehend.”

How does he feel about the momentous waves of change that have taken place alongside the touring exhibition of his show?

“The revolution is happening, colonial institutions are being questioned, and there is still a gathering momentum, with the masses demanding change, encouraging the conversation,” he says. “The reaction from Canadians has been really amazing and having that level of impact feels really rewarding.”

Uncovering the brutal parts of Canadian history is a theme that runs throughout Monkman’s work, “the idea that Canada is this welcoming place for immigrants, but it’s very good at hiding the darker history.”

Residential schools are part of a story that was carefully and purposefully hidden from Canadians, he says. “I’ve met people in their 60s who didn’t know about residential schools.”

For Monkman, who grew up in Winnipeg, it was strange to see Indigenous people featured in museum dioramas as relics from a pre-contact age while also seeing First Nations people in the city’s downtown core.

This incongruence extended to the canon of Canadian art, where Indigenous people had been entirely erased from the landscapes of early settler painters like Paul Kane and Cornelius Krieghoff.

Part of Monkman’s intent in employing classical painting was to return an Indigenous presence not only in art history, but history itself. This is especially critical in museum and galleries, he said.

“It’s important to engage with institutions [like MOA] to carry on the conversation, not to step away and silo yourself... I loved museums as a kid, they are such a value. Sure, there are problematic things, but it’s an opportunity to share histories, to reach out to the world. I’ve been criticized for speaking to the settler audience, and it baffles me: don’t you want to speak to the world?”

In revisiting and reinventing iconic moments in Canadian consciousness, Monkman makes use of his alter ego, a time-travelling trickster named Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, who shows up and stares down the likes of Wilfrid Laurier and John A. Macdonald. Miss Chief is present in almost every work, a demanding, compelling, occasionally buck-naked force.

In The Daddies, a subversive sendup of Robert Harris’s work Meeting of the Delegates of British North America to Settle the Terms of Confederation, a bare-bottomed Miss Chief sits atop a Hudson’s Bay blanket, easily commanding the room.

The exhibition, divided into nine chapters, reads like a storybook of horrors, albeit one that Edward Gorey might have written — violence, abuse, jail, starvation and disease. Monkman’s work combines exhaustive research with meticulous technique, but story plays a central role.

This is evident in Monkman’s painting The Scream, which recreates the forcible removal of Indigenous children by RCMP agents. But it’s also equally important in quieter works that ask for closer examination of small, often telling details.

In The Subjugation of Truth, Indigenous Chiefs Pîhtokahanapiwiyin (Chief Poundmaker) and Mistahimaskwa (Chief Big Bear) are shown in leg irons while around them, John A. Macdonald, a red serge Mountie and a Catholic priest look on, all watched over by a portrait of Miss Chief in the garb of Queen Victoria.

If Monkman gives himself a little poetic license in re-envisioning the past, who can blame him? Although a work like The Bears of Confederation that features the founding fathers of Canada being sodomized by grizzly bears might cause a bit of pearl-necklace clutching.

It’s not only Canadian politicians who come in for hardcore redress: Miss Chief also makes mincemeat of people who have dishonoured the feminine spirit and form. Modernist painters like Picasso are ripe targets. In a painting titled Seeing Red, Miss Chief is front and centre in full matador attire doing serious damage to a Cubist bull.

Humour is an important element in Monkman’s work — “I like to do things that tickle me.” It’s also a powerful strategy to reach people, he says, “to get them to let down their guard, to laugh and receive other messages from the work. Humour functions to disarm.”

There is definitely an air of agent provocateur in Miss Chief’s sassy sexy ways, but humour is an important part of Cree culture, and a method of survival.

One of the central tenets of the exhibition is the resiliency of Indigenous People. The show is dedicated to Monkman’s paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Monkman, a survivor of the Brandon residential school who never spoke about her experiences there until she was on her deathbed.

Although he didn’t grow up speaking Cree, Monkman is learning the language as an adult and discovering interesting things, such as the fact that there is no word for LGBTQ+ folk, exactly. “It’s just people who love people,” he laughs. The binary nature of gendered language is very much a European/settler construct, he says, and learning the Cree language is another way into a different understanding, a different worldview.

In creating work that enters the canon in a new way, Monkman’s intent is to rewrite history, “reaching across the next 150 years” in order reflect other truths, reveal other experiences and to make paintings so big they can never be hidden away. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: