Joe Sacco’s densely layered, documentary-style graphic novels have addressed some of the most complex places on the planet, including Gaza, the Balkans and the United States.

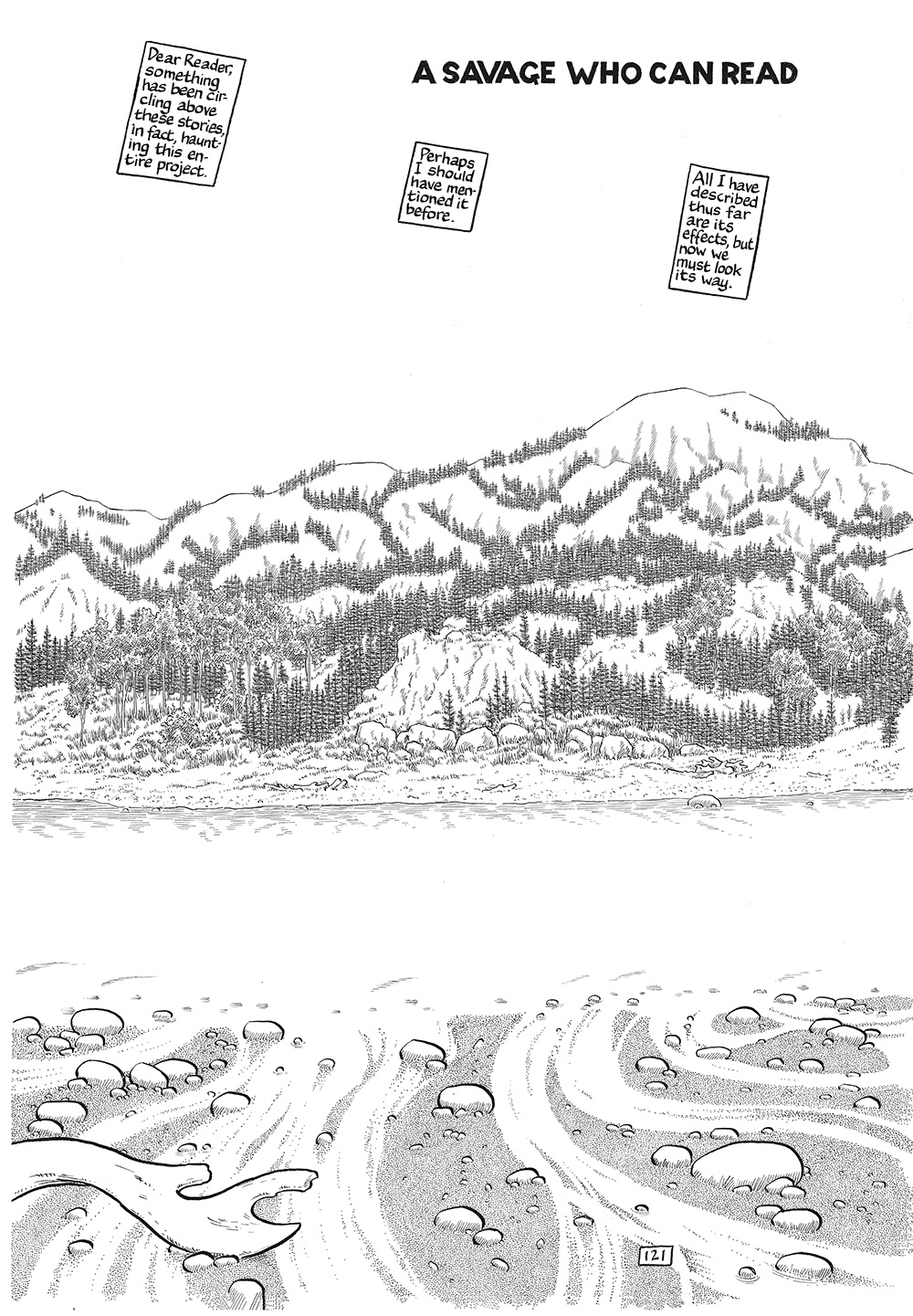

In his latest work, Paying the Land, he turns his pen to the Northwest Territories and the Dene people who call it home. Many of the stories that Sacco depicts will be familiar to Canadian readers, but perhaps less so to an international audience.

The book came about in part when Sacco was commissioned to write an article for a French magazine about climate change in the North. As he talked to northerners, he discovered the kind of ongoing suffering and torturous histories found in the world’s troubled corners.

But if you’re expecting a black-and-white story about evil corporations versus Indigenous people, you’re in for something of a surprise. Nothing is simple nor straightforward here, and Sacco takes the time to present many different perspectives, interviewing more than 35 people about their experiences.

Paying the Land is an extraordinary piece of work, toggling fluidly between the founding events of Canadian history to the current struggles over resource extraction.

The artist collected research material on two trips to the north one year apart. But the span of time covered in the book is enormous, much of it detailed in the memories of Elders from the Dene community, some of whom grew up in the bush and remember living off the land.

Paul Andrew, chief of the Shúhtaot’ine, recalls a time when people were in intimate convergence with their environment; hunting, fishing and harvesting in rhythm with the seasons. The book’s opening panels document this way of life — building canoes, making camp, tanning moose hides. It is such a rich and fascinating panoply that what comes next is akin to getting one’s head dunked in cold water.

The title of the book refers to the Dene tradition of honouring what the land provides — food, shelter, community — with gifts in turn. As one Dene Elder explains to Sacco, humans who benefit from the bounty and abundance, be it food, shelter or communion, should repay the generosity, giving back in the form of prayer or more prosaic stuff like “... water, tobacco, tea.”

As Sacco shows, this balanced way of life is the anthesis of what came after, with waves of new arrivals including French and English colonizers, the Catholic Church and oil and gas companies, all taking what they could get and leaving in their wake a toxic sludge of environmental ruin and human despair. Sacco implicates himself in this exploitive history. “After all, what’s the difference between me and an oil company? We’ve both come to extract something.”

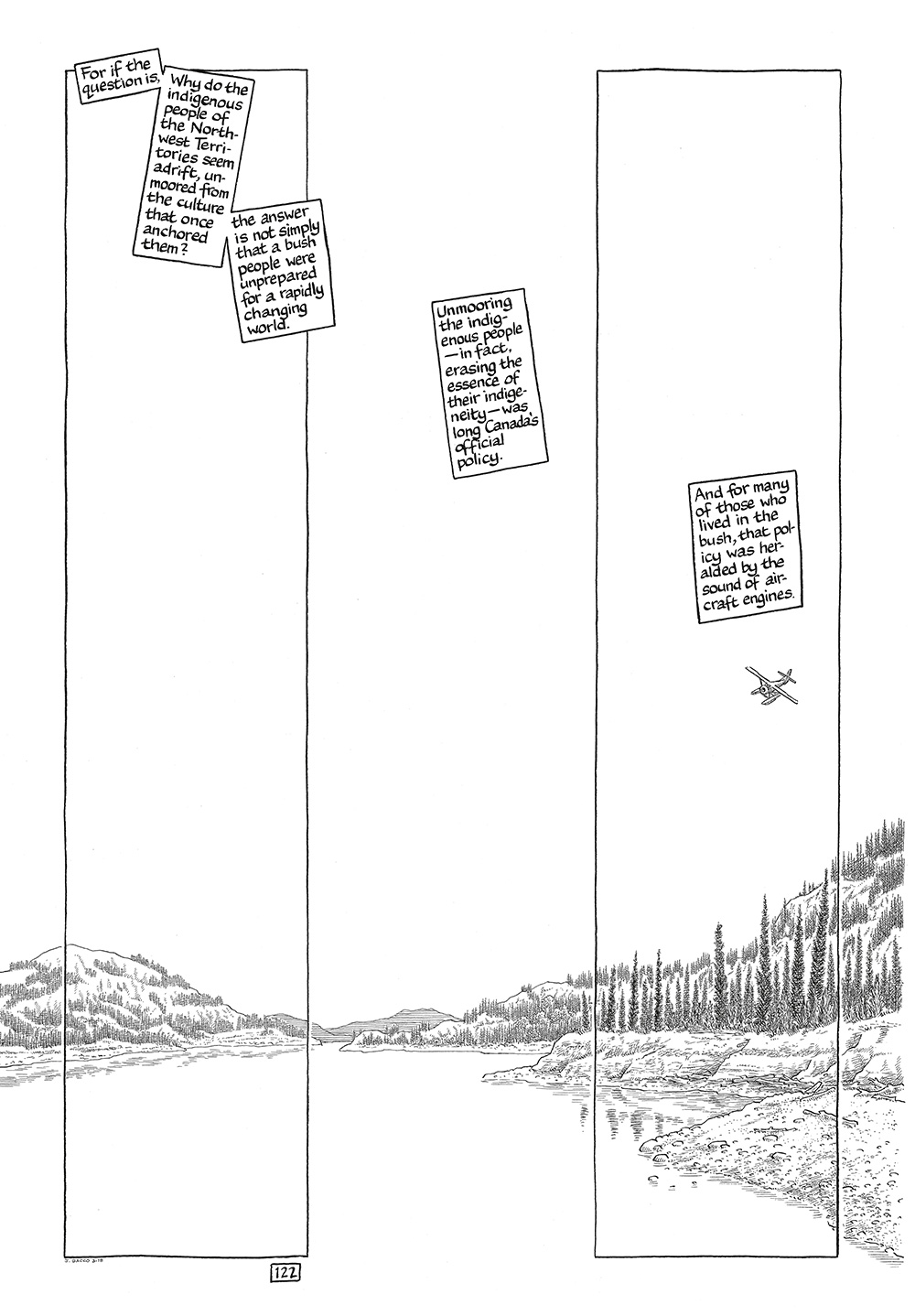

Paying the Land covers a lot of ground, moving from the arrival of European settlers to the fur trade to the Canadian government’s approach to Indigenous people. Former prime minister John A. Macdonald’s infamous words about Indigenous education linger with particular malignancy: “The child lives with its parents who are savages.... And though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write... ”

Like the residential school program, treaties were a means of exerting control not only over Indigenous people, but also on their territory. For $5 per annum and a few other sundries like bullets and fishnets, the Dene were expected to surrender all title and privileges.

Some of this history documented by Sacco in graphic fashion is almost overwhelming in its detail, but what emerges is the amount of suffering caused by the struggle between two very different worldviews. The big stories are there, but the smaller ones have a more profound impact.

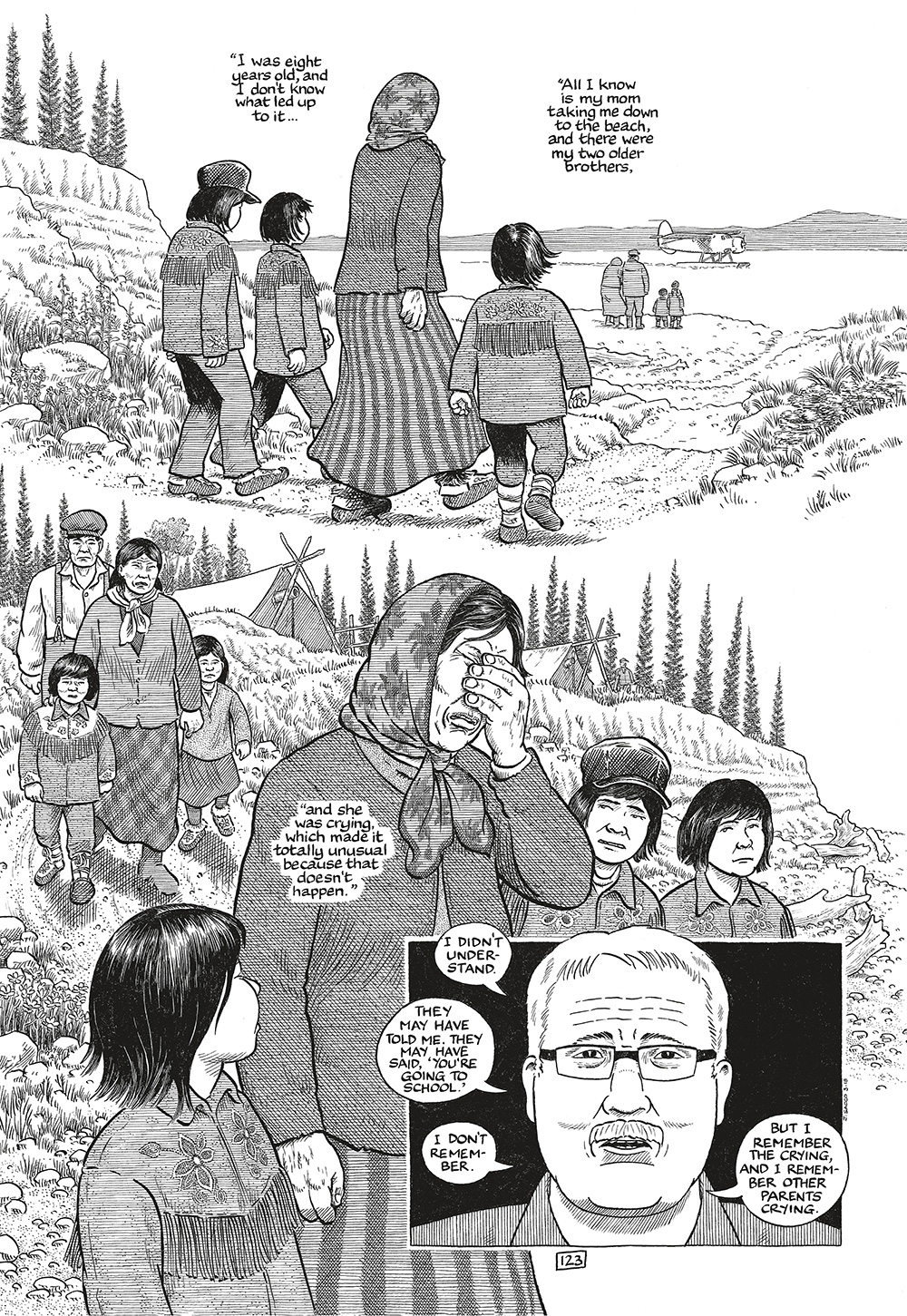

Sacco’s panels, densely hatched with lines, have the effect of conjuring more than people and places. There is an emotional impact to his work that belies the simplicity of black-and-white drawings. Empathy is a strange experience; sometimes you don’t even want to feel it, because the immersion in another person’s pain can be harder to bear than your own. In the sections of Paying the Land that detail how residential school impacted parents and children, the tiniest things etch themselves in your mind, deep as claw marks.

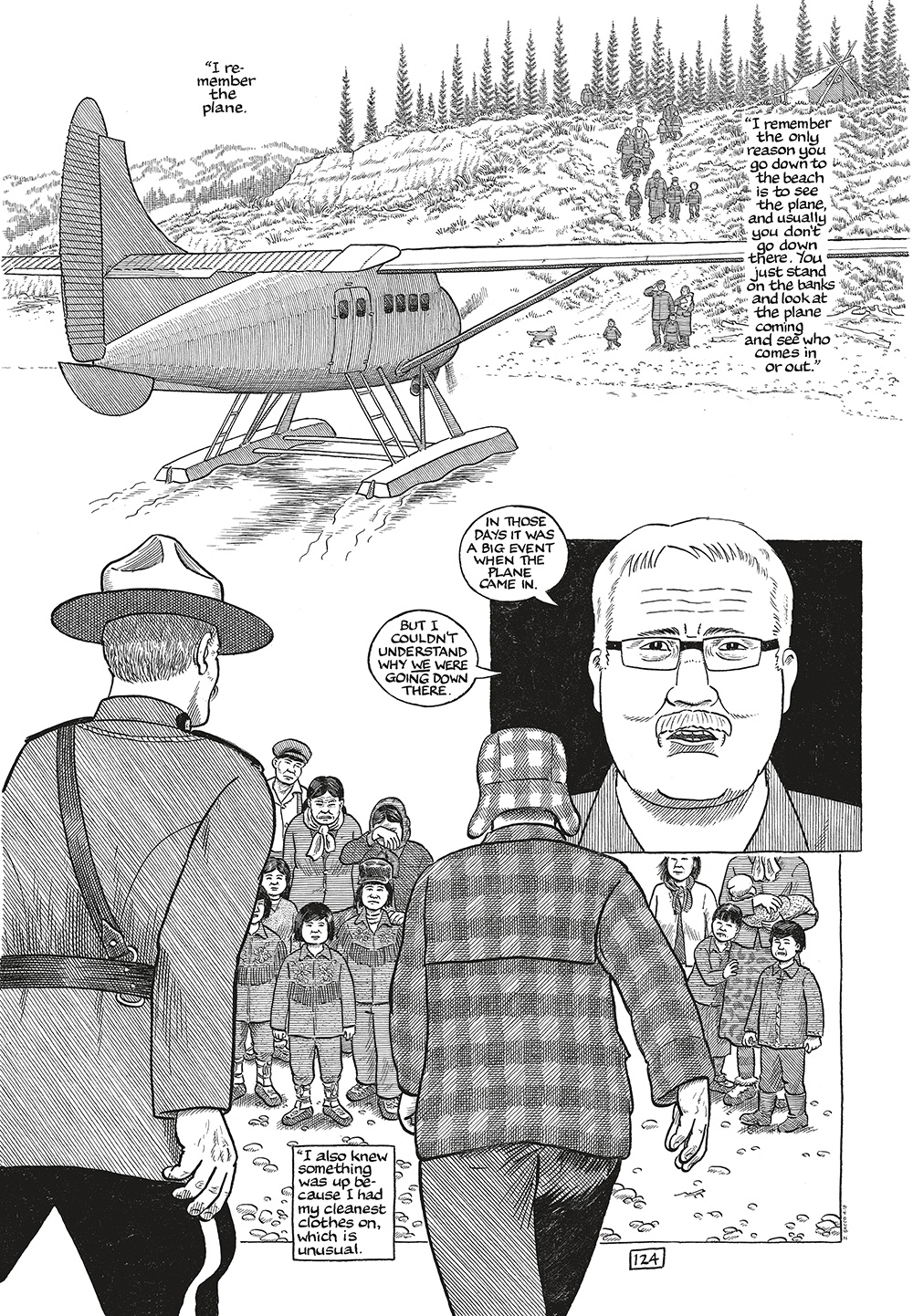

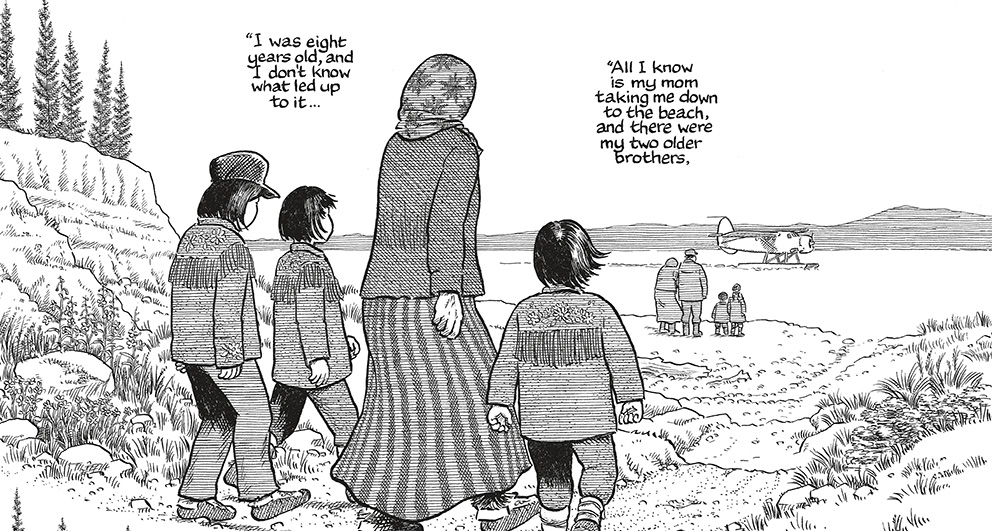

In one section, Paul Andrew remembers coming to understand why he was dressed in his best clothes on the day a float plane arrives in his remote community. The RCMP agents gave him a chocolate bar, but when he tried to give it to his mother to comfort her it was thrown back in his face. He says he wished he’d had his rifle with him to protect his weeping mom.

Taken away at age eight, Andrew’s experience was common. Flown to a distant school in Inuvik with many other children, on arrival his head was shaved. He recalls looking at another kid’s bald head and thinking he had a really ugly head, and then realizing that others probably had the same thought about him. Given an identifying number, boys and girls were divided into separate groups and the process of erasing their sense of identity was initiated.

Andrew explains how this winnowing away happened: “In residential school, there’s no individuality... You’re given a number, and you’re that number.... Every piece of clothing that you have is numbered. And the bed sheets.... Almost everything. Hockey equipment. Sporting equipment. If you got mail, for example, instead of ‘Paul’ it would be 263! It’s part of taking away that personality, you’re not particularly anybody or anything. So, they’re going to have to remake you. That’s the process.”

Others recount that even when they returned home, they were unable to rejoin their families and communities in the same way. Their language was gone, and worse, physical and sexual abuse left invisible, soul-destroying injuries. Sacco is surprised to learn that some residential schools were still in operation as late as the 1990s, their legacy continuing to enact a horrific toll on families and communities.

Levels of sexual abuse, family violence, addiction and suicide are exponentially higher in the Northwest Territories than the rest of Canada — a reality the artist depicts in a chapter titled 'Until I Black Out.' Dudley Johnson, a teacher at the K-12 school in Good Hope, instituted the idea of overnight sleepovers at the school as a way to provide some temporary protection to kids who were being abused at home. One young girl, when asked what she planned to do on the weekend says, “I’m going out to get drunk until I black out... that way, I won’t know who abuses me. I won’t remember.”

How do you repair or remediate this level of suffering? The book doesn’t offer any easy answers. But it does find sympathy and compassion for even the most broken of people, whether it’s young Catholic nuns removed from their own families, charged with enforcing the subjugation of an entire group of people, or older people trying to escape the cycles of addiction and violence. As Sacco shows, even in the harshest of circumstances, moments of care make themselves known. Some of the people he talks to recall the kindness of individual teachers or local priests who tried to understand the Indigenous culture.

Despite the pain and bleakness that it documents, Paying the Land is threaded through with moments of resilience, flinty humour and community celebrations. In Fort Simpson’s annual Beavertail Jamboree weekend, Sacco captures the fierce competition as the local people come together to match their traditional skills in games of speed and competency. Residents compete to see who can split the most wood, boil water the fastest or make the best bannock, and there is palpable joy in evidence.

As communities finding their way back to traditional culture, there is a sense that hope, fragile but tenacious, has returned. It might be a small flame, but it is growing. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Politics, Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: