- Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History

- Beresta Books (2016)

Canadians, having just weathered our federal election and watching the United States revving up for its own, may wonder at the polarized moods on both sides of the border. Albertans angrily applaud a premier who blames nefarious outsiders for thwarting the oil affluence to which they are entitled. A third of Americans salute Donald Trump’s populism that scapegoats immigrants for why their lives aren’t yet “great again.”

All to be expected, concludes Peter Turchin, a Russian-born scientist now based at the University of Connecticut, Vienna’s Complexity Science Hub, and Oxford. After publishing several other books, Turchin brought out Ages of Discord in 2016, as the U.S. election was about to deliver Trump to the White House.

Turchin is a major exponent of cliodynamics, a new discipline which applies mathematical modelling to historical events and finds that its formulas work both ways in time: they can “retrodict” past events and predict future ones.

Ages of Discord is fascinating and worrying in equal measure — in part because if Turchin is right, the U.S. and Canada are in for a very, very rough decade.

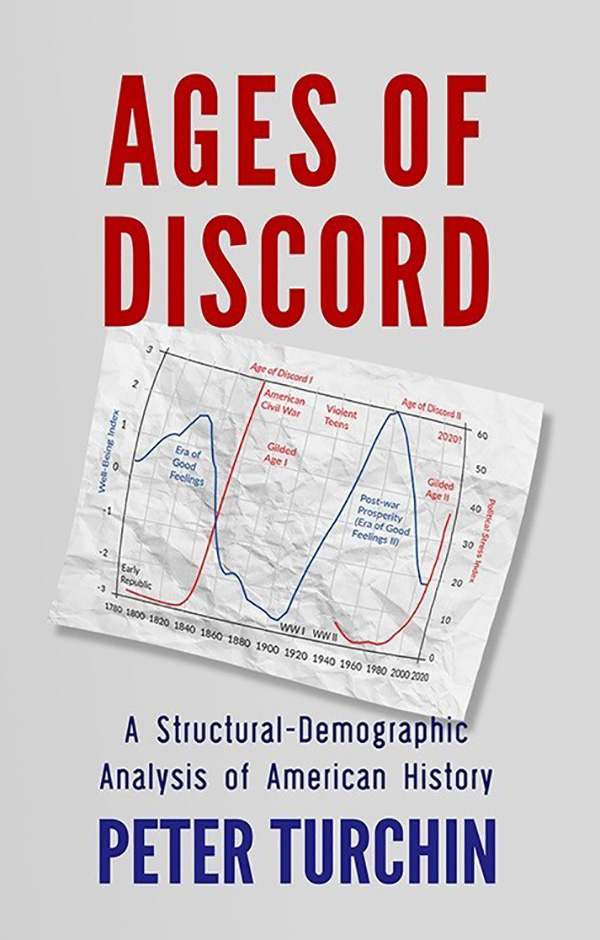

Turchin’s arguments are based on what he calls structural-demographic theory, which finds that history has cycles.

His theory focuses on four components: the common people, the political elites, the state and how their interactions create a “political stress index.” These components have operated in American history through about one and a half “secular cycles,” each beginning with very low political stress and ending in one of high political stress and violence. Immigrants and their role in the labour force are a catalyst in Turchin’s formula.

Elite overproduction

The theory says when established common Americans have adequate incomes, and the elites are united and in control of the state, political stress is low. But when elites encourage immigration to drive down labour costs, stress levels rise. As elites prosper off cheap labour, they multiply and must deal with “elite overproduction”: too many kids expecting cushy jobs (especially working for the state and in the professions), and far too few jobs available.

For example, Turchin argues that by the end of the First World War, the U.S. had cycled itself into so much labour violence and political stress that the nation verged on revolution. With Russia gone communist, radical immigrants seemed to threaten victorious America. The “Red Summer” of 1919 wasn’t communist; it was just a series of violently bloody strikes, culminating in the Palmer Raids that deported thousands of left-wing immigrants.

Thereafter, says Turchin, political stress levels dropped, but the elite had learned a sobering lesson from the violence. Immigration was shut down; if some employers needed cheap labour, too bad. The elite, as an entity, sacrificed some elite members’ needs for the greater good of the elite. That set the stage for the New Deal after the Depression hit: the elite (including patrician Franklin D. Roosevelt) realized that higher wages and more employment for the common people were just a cost of staying in power.

As a result, Turchin argues, the Great Depression was likely far milder than those of the 1870s and 1890s; now, at least, the government was hiring millions of otherwise unemployable workers. (Turchin doesn’t mention the Mexican Repatriation that sent a million people to Mexico, including many born in the U.S., during the Depression.)

Turchin’s evidence includes American life expectancy (it kept going up through the 1930s) and height (Americans kept getting taller thanks to good child nutrition). Significantly, American height has fallen again, and so has life expectancy.

So the U.S. had gone through a secular cycle from 1780 to 1930, and began another cycle with a relatively easy depression, a war that made it the world’s superpower, and then 20 years of working-class prosperity and low political stress.

Recycling

Even in the 1960s, Turchin says, the next trend was under way. Union membership fell, and wages began a stagnation from which they have yet to recover. The elite, whose income had fallen in the Depression, began to accumulate wealth again. At the same time, access to education, the professions and politics became far more expensive. So much for the North American dream of social mobility.

At the same time immigration began to increase, creating a labour surplus that kept wages stagnant. “Between 1977 and 2012,” Turchin says, demand for labour increased by only 31 per cent while labour supply grew by 56 per cent.”

Having tolerated high taxes and state involvement in the economy for 40 years, the elite began to delegitimize the state altogether. It railed against “red tape” regulation and told citizens the hard-earned taxes they paid were wasted by useless bureaucrats. A series of scandals made politics seamy, steamy and then swampy: Watergate, the Clinton impeachment, and now Trump.

Living next door, Canadians found themselves roughly in step with the Americans. We welcomed a strong state during and after the Second World War and prospered through the 1940s and '50s. Education boomed in both countries, raising competition for the elite jobs. And the immigration rate rose — but with different results.

Immigration: problem or solution?

Turchin sees immigration as a problem; most Canadians see it as a solution. Anti-immigration groups like the People’s Party of Canada found little support in the October election, unlike Trump and the Republicans.

But stresses build in both countries as more students — striving to join the elites — go deeper into debt to become lawyers and doctors, and millionaires (or those backed by millionaires) become the only ones who can afford to run for office.

So when Turchin foresees a “turbulent 2020s” ahead for the U.S., we would be wise to brace for a wave of worsening political violence south of the border, perhaps tied to U.S. economic collapse.

“Given a very shallow level of generalized trust in state institutions,” Turchin warns, “there is a real danger that investors in the U.S. debt may suddenly lose confidence.... Sudden collapse of the state’s finances has been one of the common triggers releasing pent-up pressures toward political instability.”

To the extent that Turchin’s analysis of U.S. inequality is accurate, it’s also accurate for other countries. It may help to explain the Arab Spring, as well as the current unrest in Hong Kong, Lebanon and many Latin American countries. And it may portend similar upheavals in Russia and China. The fall of the Soviet Union, Brexit in the U.K., and Trump in the U.S. all demonstrated that even a legitimate state is a fragile house of cards.

I have some issues with structural-demographic theory: it relies too heavily on a very few factors like wages; it underrates the long-term benefits of migration; and it treats national elites as the only real agents of historical change.

Despite these objections, I found Turchin’s arguments generally persuasive and thought-provoking. And alarming: It’s one thing for a scholar to discover cycles within our U.S. neighbour’s tumultuous past. We continue to live next door. So it’s quite another thing if his theories do predict the future, and we must navigate the tumult coming. ![]()

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: