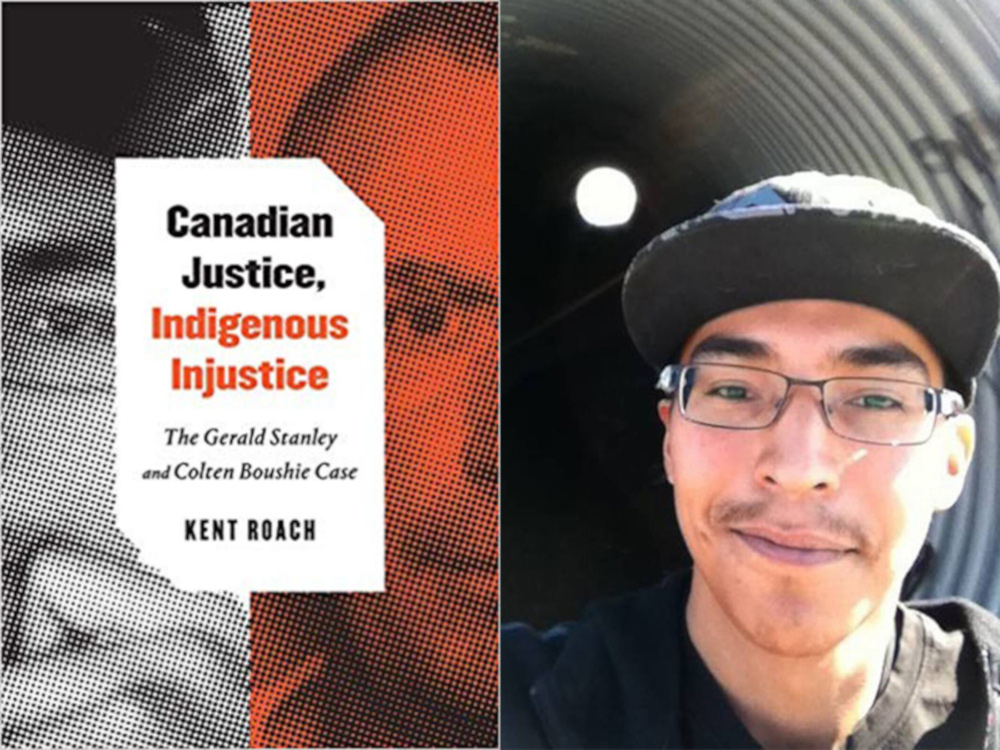

- Canadian Justice, Indigenous Injustice: The Gerald Stanley and Colten Boushie Case

- McGill-Queen’s University Press (2019)

This is a hard book to read in the spring of 2019.

The Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls has delivered its report. The powerful documentary nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up on Colten Boushie’s killing has shown us the impact of a miscarriage of justice on both Indigenous and settler communities.

Yet after so many calls for “reconciliation,” some Canadians seem more concerned about reconciling the commission’s findings — especially its conclusion on genocide — with their own self-image as egalitarian citizens of an advanced industrial nation.

Kent Roach’s book will be equally hard to reconcile with that self-image. In a meticulously researched and documented analysis of the trial of Gerald Stanley for the killing of Boushie in 2016, Roach exposes a whole system designed to maintain inequality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

In the aftermath of Stanley’s acquittal, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau got into trouble for saying “we must do better” in future such cases. He was simply pointing out the obvious gap between justice and present Canadian law. Roach makes “doing better” look almost impossible.

The roots of injustice run generations deep, back to the 1870s. Most of us have only a vague sense of the violence with which newborn Canada extended its power and values over the Prairies and British Columbia. The Hudson’s Bay Company that once ruled the West had let its Indigenous customers and fur suppliers get on with their lives. Ottawa considered them obstacles to progress.

So Treaty 6, which ostensibly defined relationships between a sovereign Canada and a sovereign Cree nation, was an agreement lost in translation and Canadian bad faith. When eight Cree were involved in a violent incident, Sir John A. Macdonald ordered that they be charged with murder and therefore face the death penalty. Public hangings, he advised, “ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs.”

Within a few years, Treaty 6 expedited the reduction of the Cree to a few scattered reserves, which they couldn’t even leave without a pass granted by the local Indian agent. (Roach notes that this system was later adopted by the South African government to reinforce apartheid.) Whites settled the Prairies and regarded the Cree as a nuisance, to be assimilated or destroyed by the residential schools.

A dangerous place for Indigenous people

Roach devotes most of his book to detailing how, by August 2016, rural Saskatchewan had become a dangerous place for Indigenous people in general, and 22-year-old Colten Boushie in particular. The law was settler law, with no regard for Cree law. “A man’s yard is his castle” was a principle of white farmers, who endured theft and vandalism made easy in a region where police were far away. And they were prepared to defend themselves and their property.

The police, meanwhile, were hostile toward Indigenous people; in the 2000s, the Saskatoon cops would take drunk or disorderly people far out of town in the dead of winter on starlight tours and leave them there to survive or die.

So when Boushie and his friends drove into Gerald Stanley’s farmyard with a flat tire, events rapidly escalated until, as Boushie sat behind the steering wheel, Stanley fired a bullet into the back of his head.

Roach makes it clear that we’ll never know exactly what really happened that afternoon. The police response was appallingly incompetent; they arrived promptly and in force in an under-policed area, but they mishandled the crime scene and let crucial evidence disappear in that night’s rainstorm.

Meanwhile, other officers arrived at the Red Pheasant reserve, brutally informed Boushie’s mother that her son was “deceased,” and then searched her home as if he had been a criminal and not a victim.

Events then proceeded as the system required. Stanley’s lawyer used five of his peremptory challenges against visibly Indigenous potential jurors, ensuring an all-white jury. Roach notes that few Indigenous people are available to serve on juries at the best of times: trials are often held far from reserves, and the pool of potential Indigenous jurors is further limited by various laws and regulations.

Despite this obvious bias, the Crown prosecutor did not object to the challenges. Despite a flood of racist messages on social media after the shooting, which even triggered a protest from then-premier Brad Wall, the prosecutor didn’t ask potential jurors whether they might be racially biased.

Bias turned up outside the courtroom, with every Indigenous protest drawing masses of RCMP as if the protestors were expected to turn violent. That expectation was suggested again when Stanley was found not guilty (a verdict that seemed to surprise him), and he and the jurors were rushed out of the courtroom.

This will be on the final

Roach devotes much of his book to a meticulous examination of the killing, its aftermath, and the trial as simply one example of an ongoing conflict between Canadian settler law and Indigenous law. He looks at many other cases, both before and after Boushie: the precedents they set and the weaknesses they revealed in the Canadian system. The effect on the reader is like taking a really good course in law school, without having to take the final exam.

The final exam is reserved for the system itself, and the system flunks — or, at best, scratches for a D-minus. “The Stanley case,” Roach writes, “reveals deep problems in the RCMP, the jury, forensic science, and the ability of criminal trials to discover the truth. All of these institutions are notoriously difficult to change.”

In his concluding chapter, Roach builds a final exam out of questions that could scarcely be answered short of revolution. Can we deny history? Can we deny racism? Can we reform the jury system? Can we devise alternatives to criminal trials in cases with enormous political implications? Can we break stereotypes that associate some people with crime and others with virtue under assault? The RCMP has been struggling for years with its own racism and sexism and PTSD issues; as one Indigenous woman has asked, “Why can’t we have talking circles for the RCMP?”

The pass-fail question may be: Can we find common ground between two culturally very different systems of justice, and build a new system that respects both? Can we truly “do better”?

It is hard to imagine products of the present system, which has trained so many of our legislators and civil servants, reading Kent Roach’s book and muttering, “Oops, my bad,” and promptly setting things right. Yet another perfunctory apology in Parliament would be a mockery.

Instead of an apology followed by business as usual, Canadians need to make Indigenous justice a national priority — from the neighbourhood and municipal level on up to Ottawa. While settler and Indigenous communities start talking seriously, a Royal Commission with a broad mandate could explore the larger picture over a period of years. The Commission might issue yearly reports, praising progress and shaming failures. Provincial justice ministries could experiment with balanced juries and closer examination of racism in potential jurors, and in the ministries themselves. Recruitment and training of police officers should weed out racists just as it should weed out misogynists.

It will not be an easy or comfortable experience for anyone. The present unjust system was built over decades; rebuilding it could take almost as long. But if we’re serious about being the kind of country we think we are, this is a test we must take — and pass. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: