The age of the great white male artist is over.

Vancouver is replete with diverse artists making radical and thrilling new work, and one of the most stunning exhibitions currently on offer is the Museum of Anthropology’s Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia on the UBC campus.

The show consists of 61 pieces from nine different artists including Nonggirrnga Marawili, Wintjiya Napaltjarri, Yukultji Napangati, Angelina Pwerle, Carlene West, Regina Pilawuk Wilson, Lena Yarinkura, Gulumbu Yunupingu and Nyapanyapa Yunupingu.

I had no expectations of these women’s work before I went to the media preview. An hour or so later I came staggering out of the museum, elated and dizzy from the eye-popping colour and design on display. It wasn’t simply the beauty of the work, although there’s plenty of that. It was the conversation that unfolded between the body and the art on the wall, and the strange perceptual shift that happens when one looks closely.

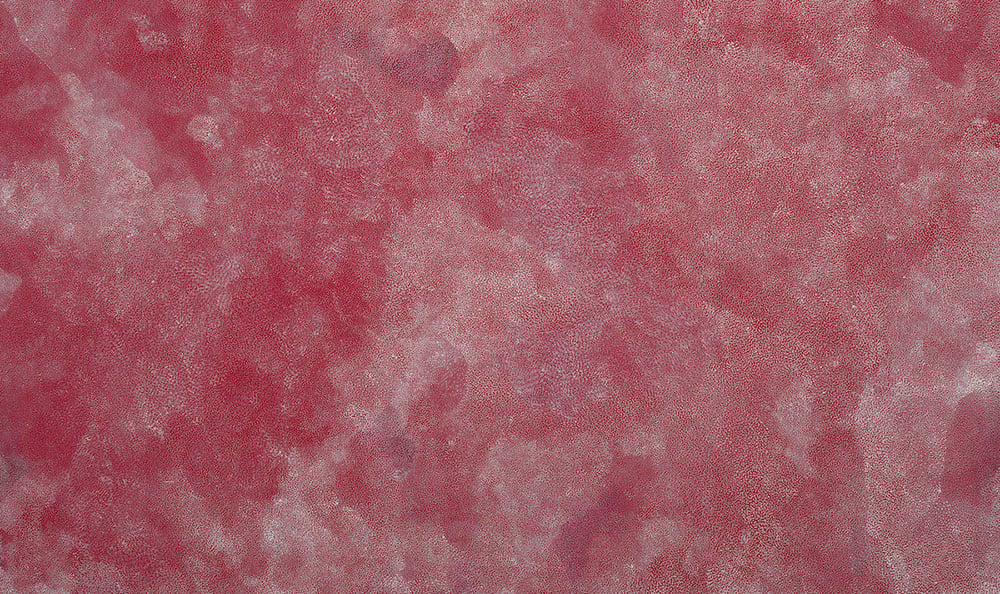

Angelina Pwerle’s large-scale painting Bush Plum (2015, and found at the top of this story) is a case in point. Filled with lush hues that made me think of pink lemonade, the nature of the painting shifts depending on where you’re standing — up close and personal or at a slight distance. If you move, the image changes, morphing from spangled cosmos to something almost bodily — a blood culture, a clutch of cells or the inside of a particularly happy vulva. Wherever you look the thing vibrates deep in your body, like a tuning fork. It is so gorgeous you want to eat it.

Introducing the exhibit, MOA’s curator of the Pacific Carol E. Mayer explained the particular vision of the women. “Their art focuses on the intimate and the infinite, the tiniest fruits of the earth and the stars above, a single stitch and the great web of creation, a brush across canvas and the unfolding infinity of being.”

The work is astounding enough, but there’s also the story of its commission, creation and collection, much of which is imparted by a wealthy white guy named Dennis Scholl. Not another one, you might think, but Scholl seems self-aware of his particular position and is charmingly self-deprecating and humble.

Scholl and his wife Debra have been collecting art since the late ’80s, working initially with organizations like the MoMA and the Tate. Eventually Scholl gravitated to Aboriginal artists and fell in love with the women’s work. At the media preview he explained that because the women were so late to painting they had a global outlook and weren’t nearly as hidebound to tradition as the men.

After 25 years of commissioning work, Scholl said he learned his lessons about working with artists: “The big decision is who, not what.” He didn’t give the women any parameters other than encouraging them to go big. Much of the work on display is the largest the women have ever undertaken. But there are also limitations in terms of what stories and cultural traditions can be depicted and shared with the outside world. “We’re only looking at shallow water,” Scholl said.

Organized initially by the Nevada Museum of Art and curated by Henry Skerritt, MOA’s Marking the Infinite comes after several other large-scale shows of Indigenous artwork at museums and galleries around the globe. But Marking is the first show to present the work of all women artists.

The Museum of Anthropology is also the only museum presentation; every other exhibition of the work has taken place in a contemporary gallery. As Scholl said of the museum, “I revere this place.” But he was also seduced by the idea of making sure the work stood on equal ground with that of the contemporary western canon. It more than holds its own — in fact, it kicks some proverbial bum.

During the media preview, Scholl and Mayer urged those present to let go of the canons of western art, but also ethnography. I can see why. As the first exhibition of its kind the work upends expectations. Canvases are displayed on the walls and the floor. There are no white cases, and a resounding lack of plinths. There is a feeling of being loosed from one’s moorings so that the sea tumbles into sky and rushes down into the earth. It is hard to orient yourself initially, but once you find your bearings an entire world opens up.

You can traipse through a great many art shows and have the work go in one eye and out the other. But this is different. Maybe it’s because it’s both very new and very old at the same time. Many of the motifs and images come from the oldest cultural heritage in the world, an art-making lineage of some 40,000 years. One of the media viewers asked Scholl why the women had never made such work before. “No one ever asked them,” he replied.

Not only were they asked for this exhibit, but also they were actively consulted on placement and installation. The show is organized in portals that are meant to draw you in beyond the shallows and into deeper water. It also allows different works to speak to each other within the context of the gallery. All kinds of interesting interconnections and relationships spring up as line meets point, colour meets form, and everything is mixed and coloured with emotion.

The most remarkable thing about Marking the Infinite isn’t simply the diversity of form or the pure, unfettered beauty. It’s the deeply intimate nature of the work. These are paintings and drawings that demand you get up close and stick your nose to the surface of the canvas to see the tiny cones of colour, deposited, one by one, using satay sticks. This use of texture, while deeply labour intensive, creates a meditative state that is almost trance-inducing. Thankfully the museum has supplied a number of low chairs that allow gallery-goers to sit and stare at the work until their heads explode, in a good way.

Autumn of the matriarchs

As Scholl explained, all of the artists in the exhibition are leaders, healers and keepers of the family. Matriarchs, in short. Whether it’s the work of Regina Pilawuk Wilson, inspired by the weaving tradition, or the more pointillist work of Angelina Pwerle, these are significant artists making work that matters. But they’re also supporting their communities through commissions and sales. The intent in bringing their work to the world is to make sure that Aboriginal culture is seen, interpreted and valued.

The MOA exhibition includes a number of videos that capture the artists at work, painting and singing and talking together. The women sit on the floor to paint and gradually build up the work, an earthly cosmos of plants, flowers, animals, ancestral landscapes and stories, laid down one mark at a time.

Although they are also working within an established cultural tradition and have to check with elders about materials, these are very much 21st-century painters. As Scholl indicates the women are much looser and more open to innovation and exploration than their male counterparts. Historically, the role of painting was ceremonial, but when the Aboriginal people were taken out of their territories and moved to settlements, art making became a way to retain cultural knowledge and tradition. The back-to-country movement in which they returned to their ancestral land did not happen until much later, but along the way new traditions were born.

Angela Pwerle’s paintings, inspired by the Dreamtime, carry with them some curious infusion of time and space, but they are also deeply grounded in the physical world. Each pointillist mark references the tiny white flowers of the bush plum plant.

As Pwerle recounts, “This painting is about my father’s country and about arnwekety [bush plum]. The flowers are there, the little bush plum flowers. That bush plum is my father’s Dreaming. That bush plum comes from Ahalpere country. It has little white flowers, then after that there is the fruit. If it doesn’t rain, the plants are dry; if it rains there is an abundance of bush plums. The flower is small when they have just come out... well, after that the fruit comes. The fruits are really nice when they are ripe.”

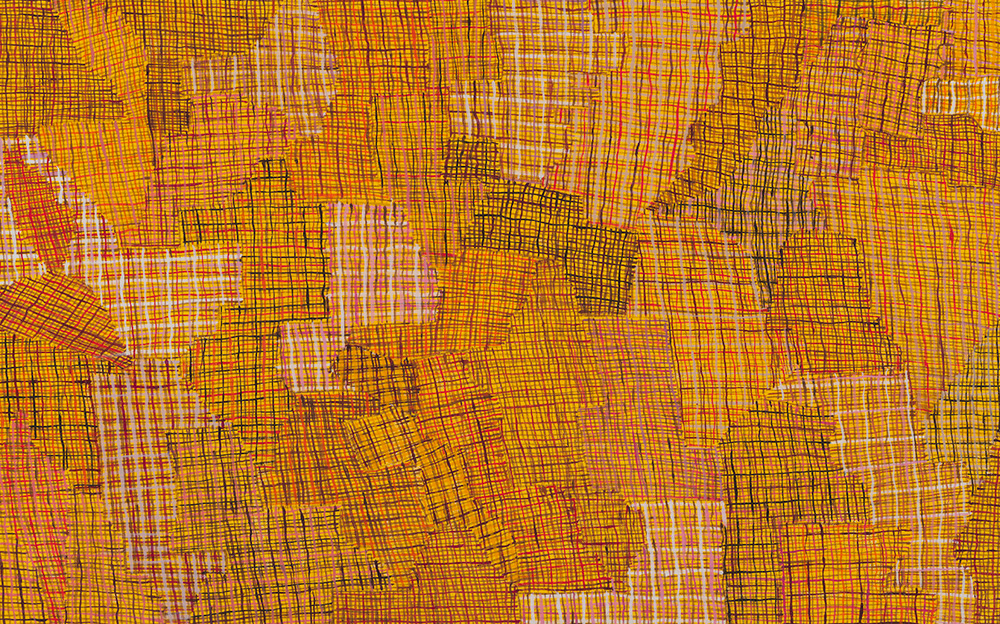

Regina Pilawuk Wilson realized that traditional weaving was dying out, and she transferred her abilities to painting. Her painting Syaw (Fishnet), in ochre-colours of brown, orange and yellow, recalls nets stitched together into something both humble and magnificent. Some of Wilson’s work is displayed on the floor. This lack of orientation creates disorientation, but it’s all in how you look at it. Viewed as a landscape it all comes together and makes sense. An endless expanse of line and colour becomes a map. Call it the big picture, because that’s exactly what it is.

In many works, clan stories are embedded throughout, visual indicators of where acts of ceremony took place. Wintjiya Napaltjarri’s painting Women’s Ceremonies at Watanuma documents in bold graphic shapes the places where women sat and talked, marked by u-shaped bum impressions. Dots and lines indicate the movement of people through a landscape in individual footprints.

Nonggirrnga Marawili’s work captures the graphic excitement of lightning hitting rocks, spraying water and fire. In her more sculptural work the bare trunks of eucalyptus trees are used as a canvas. The practice hearkens back to traditional Larrakiti burial poles that were used by the Yolngu people to hold the bones of the dead.

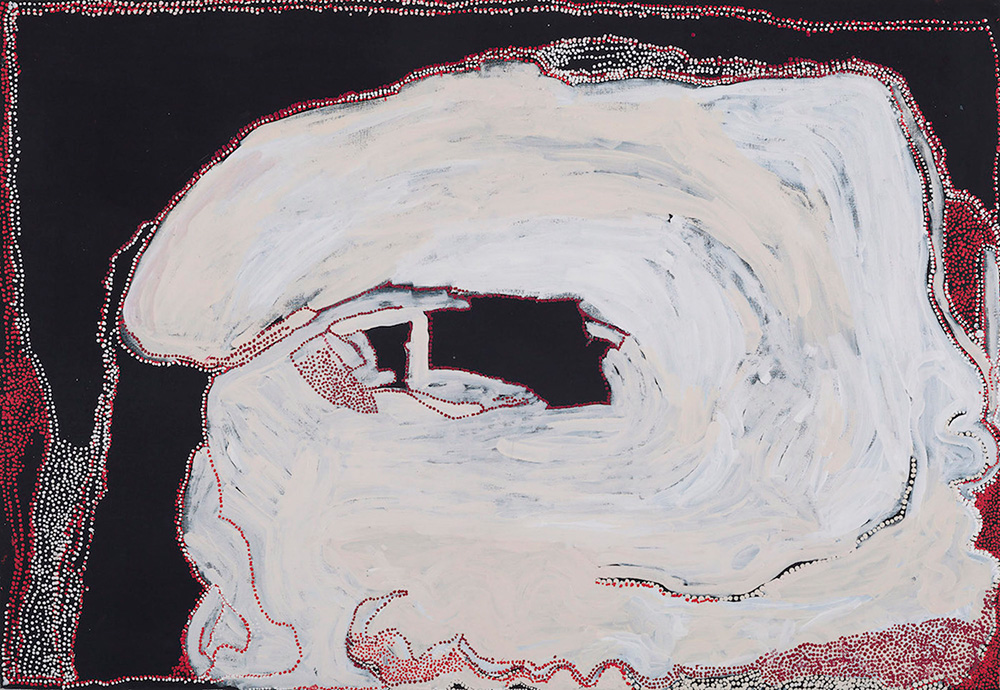

Carlene West’s more abstract and gestural work was inspired by the stories of her birthplace on the Salt Lake of Tjitjiti. Her work came as something of a surprise, Scholl said, and represented the artist’s last great burst of creativity before the onset of dementia. After West and her family were removed from their home territory due to British atomic testing, she and her husband, the artist Fred Grant, became an integral part of the back-to-country movement. Her paintings capture the relationship between people and land in a visceral, almost amniotic fashion. Many of the works resemble uteruses on a largish scale. Traceries of red and white dots like footprints are present, but it is the large stark form of the lake itself — home, birthplace and gestation point — that predominates.

If there is a single summation of the show it may be the curious connections between the big and the small, infinity overhead and tiny flowers below. Time and space blend and bleed into an endless horizon, which is probably a pretty natural way of looking at things for people who have been walking this earth for some 60,000 years.

The show ends with a large-scale map of Australia in which no territories are indicated. It is a clear reminder of the arbitrary and recent invention that is national borders. As one of the works indicates, people are always coming and going. We are all one under the stars.

Marking the Infinite runs until March 31, 2019. It is worth a trek to the museum for the sheer ravishment of Bush Plum’s shimmering colour. This is deep, quenching work. Drink it down. ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: