Walk down the main streets of any B.C. community today and you will see examples of poverty and homelessness.

While we all have a lot to say on the matter, little of that conversation is happening with children, who may not understand why someone would sleep in the streets, says Jillian Roberts, child psychologist and professor of educational psychology at the University of Victoria.

A published children’s author with the Just Enough series tackling difficult-to-discuss topics for preschoolers like death, reproduction, divorce, and prejudice, Roberts decided her next series should look at issues outside the home.

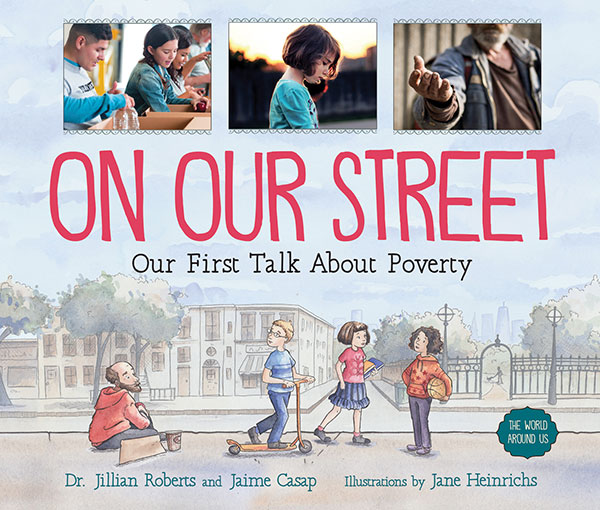

Partnering with Jaime Casap, Education Evangelist with Google and survivor of childhood poverty in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City, together they wrote On Our Street: Our First Talk About Poverty, published by Orca Book Publishers earlier this year, to help kids understand the stark inequality not only on their street but around the world. Now on it’s third printing, the book has sold nearly 15,000 copies.

On Our Street is the first in Roberts’ new book series The World Around Us, which Roberts hopes will help parents prepare their kids for growing up in a plugged in, chaotic new world.

“Children feel more vulnerable to me now than they ever have, because I think the world that we life in nowadays is fraught with more challenge,” said Roberts.

“Even with the refugee crisis, and discrimination and predjudism, those sentiments like Charlottesville, that type of thing that’s in our discourse right now, it’s difficult for children and young people to process and understand.”

The Tyee spoke with Roberts about On Our Streets, why kids are more vulnerable today, and how parents can empower their kids and strengthen their bond by answering their difficult questions.

The Tyee: How did you come to write this book?

Jillian Roberts: Jaime Casap and I were talking about my previous [book] series, the Just Enough series designed to help parents talk about challenging topics that children would be exposed to within the home, their beginning environment and community. But then once children start going to school, they become aware of the world around them, and their questions about difficult topics are going to expand and increase.

And so Jaime and I were talking about what would be the most important thing to help children understand, and we thought about poverty, in part for two reasons: I live in Victoria and seeing people on our streets has been something that my own children have asked me about over time; and Jaime grew up in Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, in poverty, and through education he was able to work for Google. So education really flipped the switch for him and allowed him to pull himself and his family out of poverty. We thought that would be the place to start.

Are you writing this whole series with Jaime?

No. The rest of the series is by myself. My last book, there’s going to be a foreword by Bob McDonald [from CBC Radio’s] Quirks and Quarks, and it’s going to be about the environment.

But the other topics in this series are going to be On The News, which is about terror and tragedy on the news and how kids make sense of that; On The Playground, about reaching out in friendship to people who might be different from you on the playground, so basically an anti-racism and prejudice book about developing kindness and inclusivity in children; On The Internet, which is about online safety; Under Our Clothes, which is about body safety and consent, personal bubbles, and that kind of thing. And the last book is called On The Beach: Our First Talk About the Environment, using water, plastics and water, and rising water levels around the world to help children understand climate change.

All of the books are designed to encourage children to ask questions and be curious. But all of the books end with a hopeful call to action so kids feel like they can be change makers and make changes in their own environments. Like On Our Street ends with ways children can help their particular communities address poverty. All of the books are designed to help children become change agents for the positive, to make their corner of the world a better place.

When does the second book come out?

It’s exciting for me because I dedicated it to my stepfather, who was a long time fireman and fire chief, and first responder. So it was particularly personal, the part about people risking their lives. It comes out on September 4th, and it’s called On The News: Our First Talk About Tragedy.

As a psychologist I work frontline with little ones. I’ve seen in the 20 years that I’ve practiced a significant shift in what children are struggling with. It’s more raw. Children are dealing with devices in everybody’s hands and the disconnect that comes with that; stumbling onto pornography, which brings up questions of sexuality and consent and the right way of interacting with other people and intimacy; then climate change; and then just our screens flooded with terrorism and tragedy, and the natural disasters that are coming from climate change.

I couldn’t find materials that I could use in my own practice or I could suggest to parents. Like a perfect example is where babies come from. I was recommending to parents that you can’t talk about pornography without talking about where babies come from, and you would have the talk about the facts of life first before you talk about pornography. And parents would say all the books out there as a resource to have that conversation are for kids just about to enter puberty. You need to have that conversation before kids get online, which means that that material needs to be softened. That’s why [the first book series is] called Just Enough: it needs to start the conversation but you don’t want it to be so extensive of a conversation that it wouldn’t be age appropriate for a little one.

And I have an adult book coming out, my first parenting book called Kids, Sex, and Screens, and that comes out November 14. The purpose of that book was to give parents guidelines about how to actually talk about pornography, and what it means for understanding yourself and your identity ,and your relationship, and the intimacy with another person, and consent. How do you have those conversations with your children so they’re not totally awkward and shut down the conversation and foster more questions.

I’ve been in this place where I’m trying to create the content that our new world needs because it’s different than what it was before, and the content that was prepared before doesn’t always apply easily to our new reality.

What’s the age range the World Around Us Series is aimed at?

This is aimed at Grades 2 to 7.

That’s pretty broad.

It is broad. So how the book works is that there is a question and answer part that’s quite soft. But then there’s side bars — and all the books are the same way — that extend the conversation. So I’ve had children, eight - nine years old, really enjoy the questions and the pictures. But then the older children are really interested in the sidebars. So I talk about the United Nations initiatives like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Child, and a little bit older children seem to be intrigued with that level. So it does span the age.

What I find interesting about the Just Enough series is that I wrote it for preschoolers, it was designed to be a picture book series for little ones. But I’ve had teachers in Grades 1, 2 and 3 still say that it’s applicable for them. It’s interesting: you're looking at the prescribed learning outcomes of the Ministry of Education and what they say should be taught and when, and then last year we had the whole B.C. curriculum change over [from Kindergarten to Grade 9] and it’s so broad now. How to position the books have been tricky, but they’re selling.

The book takes a really broad look at homelessness and poverty all over the world. How is that not confusing for kids to jump from homelessness to refugees?

Jaime’s experience and the market that he is talking to in this book in the United States would be like inner city New York. And then for us in Canada, our homeless needs, in my opinion, have more of a mental health issue to them, whereas in inner city New York it’s generations of poverty that has to do with racism and Latino communities, black communities that have just been systematically discriminated against in that space.

So it was an interesting – how do we write a book that can be wide enough to be of relevance to both the United States and Canada? That was an issue that I have to say I was super inspired by Canada’s response to refugees, and then the United States was putting up their barriers, putting up their walls, and all of the conversations in Europe about refugees and how different countries were handling the challenges that accompanied the war in Syria.

I really wanted children to think about homelessness as having lots of different reasons. When the book was just about to come out I did a talk show on the radio, and someone called in and said, you haven’t said anything about people’s choices. People make choices that leave them on the streets. Someone in Canada might think that because we’ve got such a support network, but it was important to understand mental illness, and addiction, and systematic, trans-generational risk that people were dealing with.

And then what happens with Fort McMurray when there’s fires and people are displaced and homeless because of a natural disaster? Or a war in Syria? Or hurricane Katrina? There’s reasons that people don’t have homes and why people find themselves (homeless) that don’t have anything to do with choice.

Again, we’re trying to create that little change agent in terms of that child. Will they have empathy and compassion for people that are struggling? And what can they do in their own communities to help in the ways that they can help?

So yes, and this has been a tricky thing for me: I’m trying to tackle big, challenging concepts. They’re all tricky and hard, and trying to give teachers, parents, and caregivers a way to chunk down those ideas and talk about them in a way that allows a child’s mind to get around them. As a psychologist I’m coming at this from a unique perspective.

Why did you decide to go with a text book-style versus a narrative story for the book?

I came thinking conceptually that we needed to strengthen the parent-child bond, which meant that parents needed to position themselves as the go-to person for their child whenever the child had questions.

So the books were designed to model that question and answer. The Just Enough books are always a child posing a question and the parent answering the question, and in that first series the idea was to answer it in a just enough way, not to get too much information to make it uncomfortable or not age appropriate, and to think about extending that conversation along the way through other questions, and demonstrating to a child all the questions they could ask, and demonstrating to a parent the way that they would answer.

On Our Street was this continuation of that child asking the parent. It’s not a story, but that’s the conceptual arc that we were working with.

What are the chances that this book will scare children into thinking that it could happen to them? Because it could happen to them.

Yes, it is scary, but if you live in Victoria or inner city New York, you’re going to see homeless people, you’re going to see poverty. It’s there. So it’s not like the book is introducing it for the first time to the child. So it’s designed to make it less scary so that they have a way of understanding it. But yes, they are scary concepts.

Why should parents buy this book and read it with their children?

First of all, a parent needs to see themselves in the role of a 21st Century parent. A 21st century parent needs to help their child cope with a changing, complex world. Parents are having to parent their own children with experiences that they didn’t necessarily live through themselves, like online bullying. So it’s a tough parenting journey, it’s a tough age to grow up in. Parents need to see themselves as the go-to person for their child: it’s much safer for the child, any child, to go to their parent or whoever their caregiver is, rather than ask someone on the playground or Google it.

So why would a parent want to buy this book or any of the other books? It empowers them and gives them a framework and a way to understand what their role is, and it gives them good information to respond. And it promotes and fosters that bond between the parent and the child, where the child will continue to ask difficult questions, and the parent will become more and more comfortable answering them.

One of the messages in the book is how education will help kids overcome poverty. That seemed to be a simplistic way of skirting the fact that capitalism is a big reason why a lot of people live in poverty. How helpful is this narrative, when the book itself says that poverty is more complex than that?

That was coming from Jaime’s lived experience. That was one thing that when we sat down to do the book, he wanted to make sure that that message got out.

But I could relate to it, to be honest, because neither my mom nor my dad graduated from high school. It was through student loans and our Canadian education system, which isn’t perfect but it’s pretty darn good, it prepared me for university. I was able to get an education and a good education and a long education.

The other thing is we wanted to make sure that young people left with a feeling of hope, a feeling of agency, something that they could do. So Jaime [said], what if I was a little boy reading this book: what would it leave me with? For him, he wanted to let other children growing up in Hell’s Kitchen, New York, know [to] pay attention in school, stay in school, engage in school. You have a better chance of getting ahead through education than you do making the NBA. So it was that call to action and what do you give that child to hold onto and feel hopeful about? ![]()

Read more: Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: