On a pleasant late May afternoon in 1944, young Helen Callaghan posed along the base line with her Millerettes teammates at Nicollet Park in Minneapolis. Their opponents, the Rockford Peaches, lined up along the foul line in front of their dugout. The two teams formed a colourful V-for-Victory pattern.

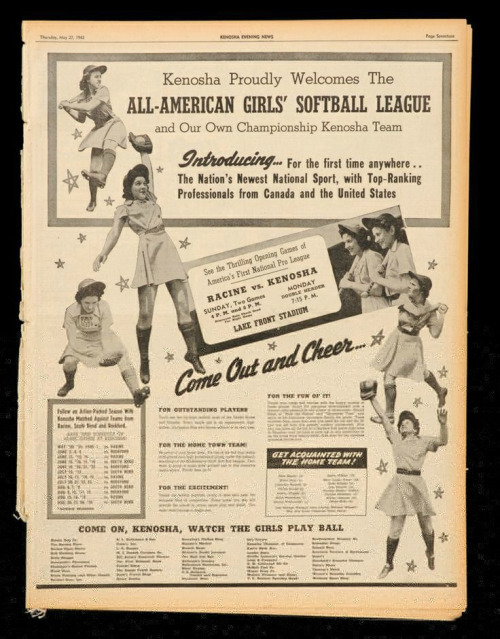

The mayor’s wife threw out the first pitch and was presented with a bouquet of flowers in return. It was opening day for the expansion Millerettes, one of two new teams added for the second season of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. As war raged overseas, women were hired to build tanks and planes, to deliver the mail and groceries, and a lucky few hundred got to play pro sports to help maintain morale on the home front.

One of the recruits was 21-year-old Callaghan, a spritely 5-foot-1, 115-pound outfielder with the speed of an Olympic sprinter. Her work wardrobe consisted of metal cleats, socks folded over at the calves and a uniform with a looped belt, a bodice lapping from the right to the left held in place with three buttons and a skirt ending above the knees. The city’s crest was on her chest and the league’s patriotic logo on a sleeve. Atop her unruly coiffure, she wore a maroon cap with a circled M.

Callaghan was a star of Vancouver softball and had been scouted at the sport’s world championship tournament in Detroit the previous summer. She left her family in British Columbia for the adventure of a life on the road, earning $65 weekly to play a game she loved.

On the day of her first game, the front page of the Minneapolis Morning Tribune heralded the impending capture of an Axis capital with a banner headline reading: YANKS WITHIN 16 MILES OF ROME. Inside the paper, on page 6 of the May 27, 1944, edition, a smaller headline on the sports page reminded readers: “It’s powder puff baseball in Nicollet opener today.”

The Millerettes lost the opener, by 5-4, though Callaghan, batting second in the order, hit a single and caught a fly ball in right field. Her team, coached by former major league catcher Bubber Jonnard, struggled on the field and at the gate, spending the last half of the season as an orphan team, playing all games on the road.

By then, Helen had been joined by her sister Margaret, older by 15 months, who got permission to leave her wartime job as a supervisor at the Boeing plant on Sea Island, south of Vancouver, where bomber midsections and flying boats were built by 7,000 workers. The sisters lived out of suitcases through the end of the summer. The itinerant nature of the job didn’t bother Helen, who hit .287 to finish in second place in batting in the league.

Mandatory charm school

The Millerettes were dispersed after the season with both sisters assigned to a new team based at Fort Wayne, Ind. They were called the Daisies. At spring training, players on teams with names like Chicks and Belles and Peaches learned to bunt, to steal a base and to apply makeup. They studied the baseball rulebook, as well as etiquette guides. There was to be no smoking or drinking in public; no fraternizing unescorted with men; no uniforms in the stands; no slacks off the field. Each team had been assigned a chaperone whose duty it was to ensure the athletes were seen to be fast only on the base paths.

At mandatory charm school, the players were told to be “neat and presentable in your appearance and dress, be clean and wholesome in appearance, be polite and considerate in your daily contacts, avoid noisy, rough, and raucous talk and actions and be in all respects an All-American girl.”

They were called the Girls of Summer, Diamond Damsels and Belles of the Ball Game. What was treated as a novelty by male sportswriters soon proved to be a showcase for serious competition. Many suffered terrible raspberries on their bared legs from sliding on dirt. There were even beauty instructions on how best to cover such abrasions.

“We were supposed to play like men,” Helen Callaghan once told People magazine, “but look like women.”

The Daisies had several Canadians on the roster, including Penny O’Brian, known as Peanuts, an outfielder from Edmonton; Arleene (Johnnie) Johnson, an infielder from Ogema, Sask.; Audrey (Dimples) Haine, a pitcher from Winnipeg; Agnes (Aggie) Zurowski, a pitcher from Regina; Betty Carveth, a pitcher from Edmonton; and, Yolande (YoYo) Teillet, a catcher from St. Vital, Man., whose grandfather was Louis Riel’s younger brother. The team chaperone was Helen Rauner, who had been an executive with the International Harvester Company, while the manager was Bill (Wamby) Wambganss, who forever earned a place in baseball lore by making an unassisted triple play in the 1920 World Series.

The presence of a chaperone and the threat of fines for not following the rules of conduct ($5 for a first offence, $10 for a second, suspension for a third) did not prevent the young athletes away from home from behaving like young athletes away from home. “We did a lot of short-sheeting,” Marge Callaghan once told me. “We’d hide brassieres, or slip a rubber snake into a chaperone’s bed. We were always sneaking out on dates. How could they keep track of 19 girls at once?”

The sisters had different temperaments. Helen was quiet, serious, competitive, while Marge was brassy, chatty and fun loving. Helen, a left-handed batter, was a proficient drag bunter, maybe the best in the league at deadening a pitch along the first-base line as she raced for the bag. Marge was a home-run slugging power hitter who is credited with hitting one of the longest homers in league history.

The sisters grew up in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, where they were the fourth and fifth of six children born to the former Hazel Terryberry, a scavenger’s daughter, and Albert Callaghan, a machinist and truck driver. He was Catholic, she Protestant. They were wed in a Baptist ceremony at the bride’s parental home. The girls were aged nine and eight when their mother died on Dec. 6, 1932. Their father remarried and the former Ann Muirhead delivered three more children to the family.

Marge and Helen played soccer, basketball, lacrosse, softball and hockey through elementary school and on into their years at King Edward High. Helen was a track star as a sprinter. They became top players on the sandlot at Centre Park, a rickety wood stadium on the northeast corner of Vancouver’s Broadway and Fir. (An oddity of the park was an outfield fence that in left centre-field jutted back towards home plate to make room for the side yard of a house on West Eighth Avenue.) Both sisters played for the Young Liberals, a club sponsored by the political party. On a tour of Oregon in the summer of 1940, a newspaper heralded the pair as the outstanding “feminine athletes” of Vancouver, describing the 17-year-old Helen as “pretty” and a “handy hitter.”

Three years later, their team, since renamed Mutuals after a new sponsor, won the Western Canadian championship to qualify for the Amateur Softball Association world championship to be held at Detroit. The Mutuals played exhibition games on Vancouver Island to raise funds for the war effort before playing warmup games as they crossed the prairies on their way to the Motor City, where they defeated teams from Moose Jaw, Sask., and Cleveland before being eliminated by the New Orleans Jax, who went on to win the tournament.

League born in wartime

Baseball scouts attended the tournament. They were looking for talent to stock a new so-called Glamour League, the brainstorm of Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley, the chewing gum magnate. He figured a women’s circuit would bring more fans to his baseball park, the famed Wrigley Field in Chicago. A women’s league was an insurance policy should major league baseball suspend play for the duration of the war. In the end, the U.S. president decreed baseball should continue to be played at all levels and the league never played at Wrigley. Teams were established in lesser Midwest cities such as Rockford, Ill., Muskegon, Mich., and South Bend, Ind. The first games were played 75 years ago last week.

Back in Vancouver, the sisters had moved out of the family home to join a third adult sister in sharing rooms in a house on East 11th Avenue at Clark Drive. The three all worked in the sprawling Boeing Production Plant, which still stands at what is now the South Terminal of Vancouver International Airport. Marge, who wore a kerchief on her head and coveralls like Rosie the Riveter, supervised women who stamped identification numbers on bomber parts, ensuring they did not damage the fragile sheet metal through eagerness or carelessness. She earned $24 a week for eight hours a day for six days a week. When she finally got permission to leave her war job and join Helen with the Millerettes, she nearly tripled her pay.

The presence of her sister at a game possibly saved Helen’s life. She collapsed at home plate during a game in 1946. She was diagnosed with a tubal pregnancy and when doctors were unable to reach her husband, Bob Candaele, whom she had married after the 1945 season, Marge gave permission for the surgery. Helen recovered, only to skip the 1947 season with a successful pregnancy.

Helen played five seasons in the league, while Marge lasted eight seasons and played more than 700 games.

The league folded after the 1954 season, a victim of televised major-league games and a conformist decade in which a woman’s place was seen to be at home, not at home plate.

Baseball mom

After retiring as a player, Helen Callaghan dedicated herself to raising a family of five sons, four of them born in Vancouver. She and the league’s other pioneering women went back to ordinary lives as teachers, secretaries and homemakers, their story forgotten for three decades.

Helen’s youngest, Casey Candaele, who was born in Lompoc, Calif., showed an aptitude for baseball. His mother encouraged him to develop his skills. “She would hit ground balls and throw batting practice,” he told me recently. “I thought everybody’s mom was doing that.” She told him she had played pro ball, but he always assumed she meant softball. As he grew older and started being scouted, she emphasized the importance of being mentally tough and alert. “You can’t have a bad day hustling,” he remembers her telling him.

Candaele was signed by the Montreal Expos and after a few seasons in the minors made his major-league debut in 1986. He was small — listed at 5-foot-9 — but versatile, playing all three outfield positions and three of four in the infield. He hustled, earning the nickname Mighty Mite, and finished fourth in rookie-of-the-year voting in 1987. Montreal fans adopted him as a favourite for his spirited play. He showed a rare display of power in one game at Olympic Stadium, punching the ball into the front-row seat adjacent to the right-field foul pole, just beyond the 330-foot sign down the line, for his first home run. The team replaced the blue outfield seat with a yellow one to jokingly mark the shortest home run in the stadium’s history. The only other yellow chair in the outfield was about 200 feet farther away from home plate to mark where Willie Stargell hit the stadium’s longest home run.

Even after Candaele made the big leagues, his mother had advice for the young hitter. She disdained the light bat he used, thinner than the one she’d used decades earlier. “What are you using this toothpick for?” she’d ask. “This thing is too small.”

Candaele lasted nine seasons in the majors with the Expos, Houston Astros and Cleveland Indians. His mother caught him in action in several games, though she could not bring herself to watch when he was at the plate. “Did he do good? Did he get a hit?” she’d asked a companion as she averted her gaze. Her son enjoyed hearing those tales. “It meant she was out there playing with me,” he said.

Hollywood tells the story

Meanwhile, an older son, Kelly Candaele, and his friend Kim Wilson produced a documentary on the All-American league, which in turn sparked the Hollywood movie, A League of Their Own.

The 1992 film, directed by Penny Marshall, put actors Tom Hanks, Geena Davis, Madonna and Rosie O’Donnell into uniforms on the field and in the locker-room, giving the world the catchphrase, “There’s no crying in baseball.” Their dramatized characters were an amalgam of the real-life stars of the league — Faye Dancer, Pepper Davis, Dottie Schroeder, catcher Mary (Bonnie) Baker of Regina, Sask., among others. At the heart of the story are two sisters who become on-field rivals, and it is not hard to see where the inspiration came from.

The movie revived interest in the league and the players. The 64 Canadians who played in the league, about one-tenth of the total, were inducted as a group into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame at St. Marys, Ont., in 1998. At Cooperstown, N.Y., a permanent exhibit of women in baseball highlighted the stars of the All-American league.

Until the movie came out, most of the former players went about everyday lives in obscurity. Many had not even told their children. “It just wasn’t something we talked about,” Marge Callaghan said. Betty (née Berthiaume) Wicken, who had been recruited out of Regina, once told me: “I never said a word all those years. Nobody seemed to know about it, it never came up, so I didn’t say anything.”

The women remembered their playing days fondly. Penny (née Martiniuk) Cooke had been working as an $18-a-week cashier for Bill’s Taxi in Saskatoon when she got a spot on the Daisies alongside the Callaghan sisters. She left a six-month-old daughter in the care of her sister to go south for the season. When Life magazine featured the league in a photographic essay in the Jun 4, 1945 issue, Penny Martin, as she was then known, was shown making a dramatic slide into third base. “I was born to play ball,” she said. “The girls played like men.”

To the league’s shame, the circuit remained segregated until the day it went out of business seven years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s colour bar. No African-American players were permitted to sign. Toni Stone, an infielder born in Minnesota, turned 23 years old when the Callaghan sisters joined the Millerettes in her home town. She was never given a chance to play, instead becoming a footnote in baseball history as the first woman to play professionally for a Negro League team.

Even as the league’s 75th anniversary was being celebrated, the festivities were briefly interrupted to acknowledge the death of former player Mary (Wimp) Baumgartner, who died at 87 in Indiana on June 2. Only a handful of the Canadian players survive. It is a roster that becomes shorter with each passing season.

The obituaries of some former players also reveal long-held secrets. Female companions are named. In the 1940s, Beverley (JoJo) D’Angelo, who was openly lesbian, was cut after two seasons with the excuse that she wore too masculine a bob. The lesbians that the league’s ownership were so desperate to keep off the field have since come out of the dugout.

Helen Callaghan, who was known as Helen St. Aubin after remarrying, died at 69 in 1992. Peanuts, Johnnie, Dimples, Aggie and YoYo are all gone now, too. One of the few still with us is Helen’s sister, now known as Marge Maxwell, who worked a variety of jobs to support the two sons she raised after divorcing. She is now 96 and lives in Delta. The sisters, whose story inspired a Hollywood movie, were inducted into the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame in 2008. They left home for adventure and found plenty of it. ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: