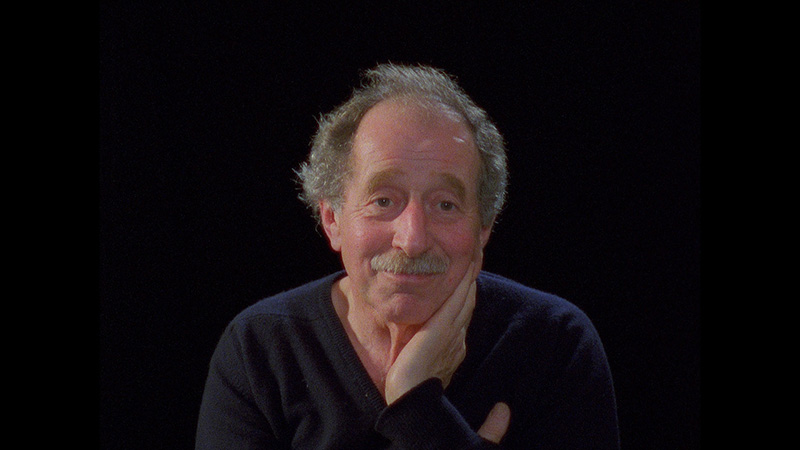

Harry Rankin was a Second World War veteran, criminal lawyer, Vancouver city councillor and socialist icon. He was described in a 2002 Globe and Mail obituary as “loud, profane, bombastic, ungracious and unforgettable.” If this larger-than-life legend and fighter for underdogs had succeeded in his campaign to become mayor of Vancouver in 1986, the city would have gone in a very different direction.

A long-awaited documentary chronicle of Rankin is finally complete. It began with that fateful 1986 campaign when Peter Smilsky, a lawyer-turned-documentarian, was shooting a film on Rankin. The project was never completed.

Fast forward to 2010. East Vancouver-born Teresa Alfeld, fresh out of film school, unearthed Smilsky’s reels in the basement of Harry Rankin’s son Phil, and completed the film with new interviews.

Directed by Alfeld, The Rankin File: Legacy of a Radical will premiere at DOXA in Vancouver on May 3.

The film is a nostalgic trip. Peter Smilsky’s 16-mm footage crackles with the energy of 1986 Vancouver, an adolescent city considering what it will become.

Vancouver is high off the attention of Expo 86, but affordability, like today, is a worry of residents. Rankin, the COPE mayoral candidate, wants to see a more equitable city, championing causes like social housing on the Expo lands. His upstart rival for the Non-Partisan Association is a young Gordon Campbell launching his political career, who wants to open the city to the world. We all know what happens next. (The late media personality Jack Webster makes a few appearances, and his charisma reminds us why they called him “king of the Vancouver airwaves.”)

Alfeld not only uncovered this historic footage in Phil Rankin’s basement, but illuminated it. She interviews politicians and activists from Rankin’s career, including Mike Harcourt, Libby Davies, Jean Swanson, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip and his wife Joan Phillip and, of course, Gordon Campbell. The film is enriched by the ability of these veterans to reflect on Rankin’s legacy decades later and how Vancouver has changed over the years. It may leave you longing for a Vancouver that never was, but could have been.

“I have a great capacity to be indignant about other people’s problems, and I have a great capacity, I suppose, to deal with other people’s problems,” says Rankin in the film. “And it seems to me that’s what I should be doing. I don’t know, what makes a dog bark? He’s built that way. What makes me defend? I’m built that way.”

Here’s our interview with Alfeld on completing the film, Vancouver politics past and present and meeting Harry Rankin through old footage and the stories of others.

The Tyee: How did you uncover the archives in Phil Rankin’s basement?

Teresa Alfeld: I finished film school in 2010 at SFU. I came to work for a small company called WorkingTV in Vancouver. We focused predominately on producing video content for unions, social justice groups, labour groups — a whole whack of folks.

Phil Rankin approached us for help sorting through what we later called the “basement archives.” He had a whole collection of material related to his dad’s career. I was tasked with the job to see what exactly was in there. He mentioned his dad was Harry Rankin, and I had certainly heard the name before, but I wasn’t familiar with his career.

I went to Phil’s, went down into the basement, and started looking at a collection of Rubbermaids and document boxes and bins. I opened one of them up and was rather astonished to find a collection of film reels, both negatives and pizza boxes full of workprints. Finding 16-mm film for a film student is always exciting. So I took them to SFU and started stringing them up and doing low resolution transfers to video, and that was how I met Harry.

What was your impression of him?

I was completely captivated by Harry, by his politics, his sense of conviction and sense of humour. And not only Harry, but the backdrop of 1986 Expo-era Vancouver. I was in my early-20s, and this was a city that I had never seen. The sense of vibrancy and energy was so compelling.

What did you do next?

I asked Phil Rankin what I was looking at, and he said, “That’s Peter Smilsky’s old documentary about my father from a couple decades ago.”

I felt a sense of responsibility when I found the footage. Not making the film was not an option.

The first step, of course, was to find Peter Smilsky. It was a bit of process. He was practising immigration law in the Ukraine. I had to find him, then gain his trust. He opened up to me about the film he had never completed as well as his close friendship with Harry, which it turned out had ended up complicating the completion of his film.

In 2014, after a few years of researching Harry and writing a treatment, I got my colleague John Bolton involved in the project. I had worked on John’s sets for years as a PA [production assistant] and AD [assistant director], and really looked up to him as a filmmaker. I asked for his opinion on the treatment and he loved the project so much he ended up coming on as my producer.

I sort of benefited from both worlds. I had the original 16-mm footage and Peter’s relationship with Harry really showed in it. I also had the distance to make the film that needed to be made without sacrificing relationships.

You’ve called this film a collage. What was it like putting that collage of voices together to paint a picture of Rankin?

For me, it was always important to have a diversity of people from his career, people from his city council days, people from his legal activism days, his family, friends, foes, and in some capacity bring all those voices together. At the same time, I didn’t want to shy away from some of the conflict that people had with Harry, particularly his sexism.

And so the term collage celebrates some of the textural differences in creating a portrait of this man.

Vancouver’s 1986 battle for mayor is a big part of the film, and we can say today that it was a turning point for the city. What was it like telling the story of this milestone?

If I were to go back in time and pick a year to film in Vancouver history, it would probably be 1986. There was so much attention on the city and so many decisions being made after Expo, like what would happen with the Expo lands.

Harry Rankin and Gordon Campbell presented very distinct and different views.

Harry wanted protections for renters and he wanted affordable housing. He wanted social housing in the proposed development on the Expo lands and to make them accessible to all people, not just those who could afford it.

Then there was the Gordon Campbell view, totally market-focused. In the film footage, Campbell said a lot about taking advantage of opportunity and of wanting to open B.C. and Vancouver up for business. It was a different paradigm than what Harry was working with. Understanding the difference between these paradigms is important today from my perspective as a millennial here hoping to continue to be able to live in the city.

The film tells us that Rankin is a champion of the people. Why do you think he lost?

I consider myself more of an armchair analyst; my sense is that it’s a number of things. You have to remember that Harry was coming with the so-called advantage of the dominant party. COPE had the majority. So often in elections there is an attraction to new, fresh candidates, regardless of their integrity or the substance of their platforms.

From watching the footage, I think it’s fair to say that Harry wasn’t quite performing as strongly as he always had. He had personal issues going on, he knew by the end of the campaign that he was down in the polls, and, really, just participating in a mayoral campaign requires a ton of endurance. The collection of issues started to wear down Harry.

You also can’t forget that Harry’s popularity as an alderman doesn’t necessarily translate into votes for mayor.

So Harry not winning was a compounding of really unfortunate issues. But that doesn’t mean that folks with fresh revolutionary and radical ideas for the city should be deterred.

We’ve got an exciting election coming up for Vancouver this year. Do you see any parallels between 1986 and today?

We’re coming up on a decision year here with Mayor Gregor Robertson stepping down and Vision’s councillors heading for the hills.

We’re seeing a new degree of interest in what possibilities are open for Vancouver. And also recognizing the outcome of the last 10 years of what the Vision council has produced.

For me, Jean Swanson is an inspiration. She has referenced Harry as an important figure in her own political development saying that “It’s time for things to be different. It’s time to stand up against development solely for profit. It’s time to stand up for all citizens of this city, not just those who can comfortably afford to live here.”

It’s been over three decades since Peter Smilsky started working on his Rankin documentary. What do you think having this time gap brings to your film?

As cool as it would’ve been to have a feature about a socialist icon here in the 1980s, I think the film is so much more powerful to have that 30 years of perspective — especially for my interview subjects, who were able to speak about Harry’s career and contributions not just in that moment, but to reflect on how Vancouverites have made a decision about where they wanted the city to go.

Would you have liked a chance to meet Harry?

I feel like I have my own conception of him. I obviously would’ve loved to have met him when he was alive. I would’ve worked on his campaign!

But there’s something interesting about having someone exist purely through other people; there’s something about that for me that is special. So I think it’s both yes and no.

The opening gala screening of the film is on May 3 at 7 p.m. at the Vancouver Playhouse, 649 Cambie St., as part of the DOXA Documentary Film Festival. You can catch an additional screening on May 8 at 6 p.m. at SFU Woodward’s, 149 West Hastings St., which will include a post-film discussion. Tickets available here. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: