- We Build BC: History of the BC Building Trades

- BC Building Trades Council (2018)

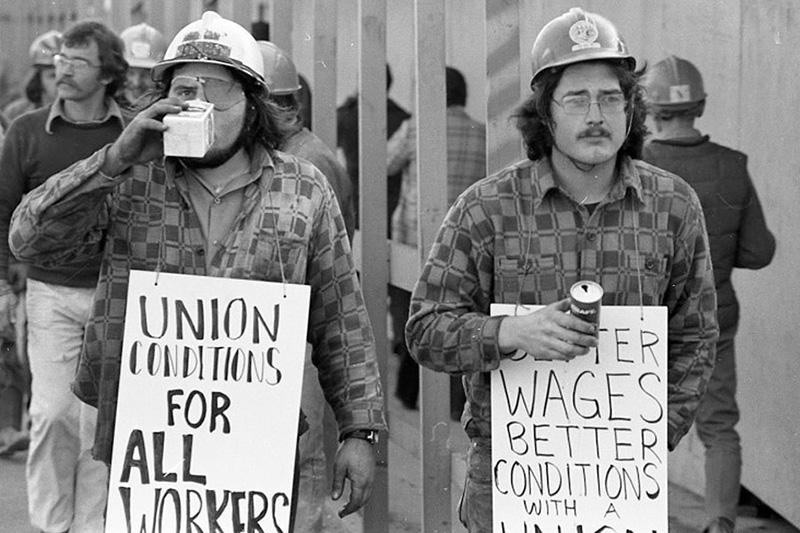

In May of 1971, strike action by construction workers once again made the front pages of the province’s newspapers — but this time the issue was the life and death of construction workers on the job.

Construction is one of the deadliest industries in the country, killing and injuring workers at a higher rate than all other industries but forestry. One of the most important challenges taken up by the unions and the BC and Yukon Territory Building and Construction Trades Council would be the job of keeping workers alive. There was a lot of work to be done.

On May 6, more than 200 workers, from seven unions, building the giant TD Tower in Vancouver, downed their tools because the employer was exposing them to one of the deadliest minerals on the planet — asbestos. And they refused to return to work until the situation was cleaned up.

One of those organizing the strike was Lewis Loftus, a second-generation member of the Heat and Frost union, whose son Lee (who would later serve as BC Building Trades Council president) remembers how bad it was then.

“I remember when my Dad came home from work from that project, he was covered head to toe with asbestos. He had a head of tall, black curly hair and it was just covered in asbestos when he walked in the kitchen door,” he said.

“Asbestos was falling into streets, covering the workers and there was no protection whatsoever.”

“The black tower breathes white death,” one worker told reporters at a noon- hour demonstration on the court house steps on Georgia Street. Carrying signs such as “Asbestos the Killer” and “Asbestos causes Cancer,” the workers demanded much tougher rules regarding the spraying of asbestos on the job site.

The use of asbestos, as it would become crystal clear over the next decade, resulted in the greatest number of fatalities in the construction industry.

Thousands across the country died and continue to die because of their exposure to asbestos. A single exposure to the substance could lead to deadly cancers, most common and widespread was lung cancer known as mesothelioma. The other main disease was asbestosis which involved destroying the capacity of the worker’s lungs.

At the TD Tower asbestos was sprayed on all the ceilings after the piping and electrical wires had been strung. Asbestos was used on almost every construction site in the province. In fact, there was a union that represented asbestos workers, the International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos Workers. Workers applying the spray wore masks but the floors were not sealed off and the asbestos floated between floors, exposing workers with no protection. After the spraying was completed and before the air cleared workers were also ordered to re-enter the area and continue work.

Although the dangers of asbestos had been known for years, the rules and regulations of the WCB, then known as the Workmen’s Compensation Board, for its use were lax, leaving thousands exposed.

Many, including some employers, refused to accept there was a real danger. Even medical experts were still dismissing possible dangers. Dr. Peter Coy, a Vancouver lung specialist, said he understood “most asbestos used commercially was safe.” Although he did add that because we “really don’t know what it is, precautions should be taken.”

Workers were clearly ahead of their employers and government agencies in accepting the dangers and they were standing firm when they met the employer. The company building the TD Tower responded by agreeing procedures were not followed and workers were exposed.

“I admit there was a problem with the cleaning up of the insulation from the floor after spraying, but the foreman who caused the problem is no longer with us,” Lawrence Zuckuk, chief superintendent of the job, told the unions.

The company agreed to isolate the spraying areas, clean up loose asbestos before workers returned and to post warning signs.

Workers rejected the company proposal, saying it did not go nearly far enough to protect workers, adding four additional demands to the list.

“Workers want no asbestos spraying between 8 a.m. and 4:30 p.m.: no sweeping of the asbestos during the same period; vacuum cleaning of the areas involved; and all asbestos-cover areas to be sealed with sealer,” said electrician shop steward George Corness. “If we get an affirmative answer to our requests by the morning, we’ll go back to work. If not, many of us won’t go back.”

Others turned their criticism to the WCB for not having clear regulations to protect workers when spraying asbestos, pointing out California and New York had such regulations.

“All we want is safety on the job. Is that too much to ask?” said Robert Dodson, a carpenter on the site.

It turned out in this case it was not too much to ask and the company agreed to the workers’ demands.

But the battle to protect workers was just getting started as each year brought new revelations about the deadly consequences of the exposure to asbestos. The Building Trades Council was central in the campaign to toughen up the rules regarding inspections. The battle to protect workers from asbestos was hampered, according to Loftus, by the long-term nature of the disease.

“You can roll in it, fill a room with it and next week and next year there is nothing wrong with you because it doesn’t kill you for 20 to 50 years,” he said. “When I would ask for protection, older guys would say — what’s wrong with you? I have been breathing it for 40 years.”

By the mid-1970s the link to lung cancer had been firmly established and council work on the issue paid off in 1978 when the WCB brought in new regulations, including for the first time regulations specifically to deal with exposure to asbestos. “Section 35 declared exposure to asbestos was an immediate endangerment to your life and health,” Loftus said. “The regulations said you had to control the exposure, it banned the spraying of it and dry sweeping. It required employers to look for alternatives to using asbestos.”

While some employers dropped the use, others found ways to get around the rules and continue the use.

“As I grabbed a box of material I noticed the John Manville sticker had been placed over the old one. I tore it off and found out that in fact the material contained 7 per cent asbestos,” Loftus said. “We ended up tossing the whole lot of it.”

Despite the tougher regulations, much work remained to be done to finally halt the use of asbestos completely. But as knowledge about the deadly nature of the disease grew so did the death toll.

Pressure from the building trades and the scientific community had begun to influence WCB policy but it would be years before proper rules would be in place and thousands more would continue to be exposed to the deadly mineral.

‘Magic mineral’ kills millions

“It is criminal to allow men to die because of their occupation,” Dorothy Dobbie was quoted as saying in the 1975 annual BCYT–BCTC report. “Why then, when statistics prove that asbestos kills, when the facts were known even before the material came into such widespread use, why is there this uncaring, unfeeling attitude toward the plight of thousands of asbestos workers?”

It was a good question.

When construction workers shut down the TD Tower job site in Vancouver in 1971, they knew asbestos was dangerous and regulations protecting them were sadly lacking. But regulators and companies had known for more than a century the basic truth — asbestos kills. Yet little had been done to protect workers.

The production and use of asbestos exploded along with the industrial revolution. Companies selling the product called it the “magical mineral” and more than 3,000 building materials and household products would contain asbestos.

But not everybody was celebrating the wonderful qualities of this mineral. In 1898 a factory inspector in England, after witnessing the rising death toll of asbestos factory workers, labelled the mineral an “evil dust.” It was linked to thousands of deaths.

Workers had been dying from the “magical mineral” for centuries. Historians reported that slaves in ancient Rome who weaved asbestos were suffering from a “breathing sickness.”

Asbestos is made up of thin filaments and its use was primarily because it was very strong and fireproof. But those same fibres are also deadly.

In 1918 a report by the insurance industry said that American and Canadian insurance companies have barred asbestos workers from life insurance because of the high rates of deaths being experienced.

English asbestos factory worker Nellie Kershall was one of thousands exposed to the “evil dust.” She died in 1924 and for the first time a coroner’s inquest was held into an asbestos death. It was revealed her lungs were peppered with minute fibres that cut directly into the lung tissue, leaving thousands of scars. The coroner ruled she died of asbestosis, a disease of the lungs.

The company, Turner Bros., refused to accept the findings, no compensation was paid and they refused to cover the funeral costs for Nellie.

With the death toll mounting, England was pressured to act and the first legislation covering the exposure to asbestos and compensation policies was passed in 1931.

A strong industry lobby was successful in watering down the legislation so it failed to provide protection for construction and shipyard workers.

John Manville was a well-known name on construction sites in Canada. The company was also one of the largest consumers of asbestos for use in construction products. Company scientists studied the impact of exposures of asbestos on mice and rats in 1941. The results were staggering — in fact so staggering the company ordered the scientist not to publish them. Years later it was revealed that more than 80 per cent of the animals in that study developed lung cancer. This would later be described as mesothelioma.

It was now known that in addition to asbestos poisoning, lung cancer was also a deadly consequence of exposure.

Building trades unions, in particular the International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos Workers, knew something was wrong as early as 1943. It was then that two U.S. locals began studying the issue and over the years saw death rates related to lung diseases at twice the normal rate.

In British Columbia the fight to protect construction workers was led by the council and it would not be until 1978, nearly a decade after the wildcat strike at the TD Tower in Vancouver, before serious steps would be taken.

It would still be years until the deadly mineral was banned from worksites and the export of asbestos would be halted.

The death toll?

The International Labour Organization estimates that 100,000 construction workers die annually from exposure to asbestos. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: