When I was a child the opera bug bit hard, so hard that the teeth marks are still visible. At the tender age of eleven I fell head over heels into the kind of obsessive, compulsive, all-consuming love that you are only capable of when trembling on the edge of pubescence.

Walking to school in Grade 7, I gravely recited the names of long-dead opera stars in an effort to build courage against the boys who called me “pinhead” and “staple face.” In vain, I tried to memorize the entire libretto for The Barber of Seville even though I didn’t speak Italian. I could easily bring myself to tears just by thinking about the plot of La Boheme.

I can hear you thinking, “What a supreme nerd.” And you would be right. But opera fulfilled a certain need for big drama, the biggest kind, epic in scope. When feelings were too enormous for a skinny body to contain, opera was the vehicle to give them voice.

Long before film came traipsing in the door, with its combination of sound and image, opera was mixing it all together into a complete art form. The Wagnerian concept of Gesamtkunstwerk incorporated story, music, visual splendour, magnificent death, immortal love, giant battles, self-immolation and stabbing, always a lot of stabbing. All the good and big stuff.

And none were quite so big as Turandot, Giacomo Puccini’s final opera, uncompleted at the time of his death in 1924.

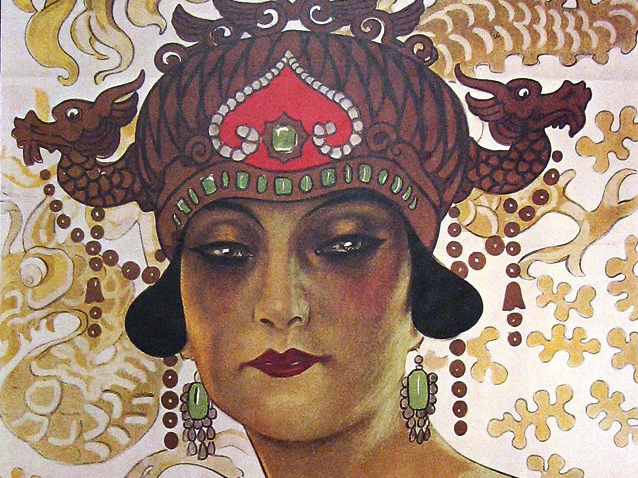

Turandot is a different kind of creature from Puccini’s other work. It is one of the rare dramatic operas where the woman gets to live. And not only live, but triumph. Turandot gets all the boys, and all of the coolest outfits. She is bedazzling in scarlet and gold, fingernails as long as rapiers, more eyeliner than is humanly possible and a mouth as red as blood

The original story, based on the Persian poet Nizami’s The Seven Beauties, inspired many different interpretations including Carlo Gozzi’s commedia dell’arte play Turandot. Puccini’s operatic version begins with a unknown man named Calaf arriving in the ancient city of Peking, just in time for the ritual slaughter of the Prince of Persia. The prince has attempted to solve the three riddles of Princess Turandot in order to claim her hand in marriage. The dude has failed, and when the moon rises, he will be ceremoniously beheaded. The crowd goes wild.

The Vancouver Opera opens its 2017/18 Season with the bloody ice princess and her would be suitor(s) today. It is a complex and complicated choice, especially in a city as culturally diverse as Vancouver. Opera’s race problem pops up with some regularity and pains have been taken in this production to deal with it head on.

In the VO program notes, a statement from stage director/choreographer Renaud Doucet and set/costume designer André Barbe says: “In 2009 a consortium of five U.S. companies led by the Minnesota Opera asked us to create a new production. The mandate was to create a Chinese-inspired grand spectacle, but we wanted to ensure that the spectacle remained in service of what made the opera pertinent in the first place... For all the characters it is their humanity and personal growth that is most important. It is, after all, the point of life, and of all fairy tales.”

That is precisely what Turandot is, a fairy tale, albeit one that is bloody, a bit nasty, and still undeniably sexy.

The 1957 RCA Victor box set of Turandot that my grandmother had featured Birgit Nilsson, Jussi Björling, Renata Tebaldi and Giorgio Tozzi, all presided over by conductor Erich Leinsdorf and the Rome Opera House orchestra and chorus. The recording was made during a notoriously hot summer in Rome, and tempers were also on the warm side. Swedish tenor Jussi Björling, soon to die from a heart attack, looks hotter than hell in the production photos, but none of this comes through in the recording. The opera roars and stomps, ferocious and bright with spears of sound that teeter perilously on the edge of something brutal, almost ugly. It is the sound of sex, at least, what a prepubescent hick thought sex was.

Turandot was the role that made soprano Birgit Nilsson not only famous, but also rich. She performed it more than 300 times. In the 1957 recording she is at the peak of her considerable powers, with a voice as stratospheric as an intercontinental ballistic missile. She is met and matched by Björling. In the opera’s infamous riddle scene, the ultimate battle of the sexes, Calaf and Turandot square off, circling each other like prize fighters, equally matched in their respective powers. Nilsson and Björling’s voices twine together, each trying to overpower the other, neither succeeding but forcing each other higher and higher, until the chorus subsumes them both, drowning all in waves of sound.

All of this played out on the moviola inside in my head, which created visuals to accompany the music, cutting in and out of the action, panning across the shifting crowd, electrified with a viral form of hope, as each respective riddle is posed and then answered. The music coils, pools, in descending winding loops of unease and fear, then rising into an ecstatic scream of joy, buoyed by imperial trumpets. There is no way to resist its insane, almost garish, power.

It is certifiably cinematic.

But there is more. The opera also contains some of Puccini’s most delicate melodies, inspired by Chinese folk song. It is this gentleness, tender as petals unfurling, that gives the opera its famous leitmotif. After Calaf answers Turandot’s riddles correctly, he makes her a deal. “You do not know my name. Tell me my name before sunrise, and at dawn, I will die.” Leading, of course, to the one aria that everyone, even football hooligans, know. The version of Nessun Dorma that Björling gives is wonderful, but even better is a live version performed at a 1944 outdoor concert in Stockholm.

It is easy to get carried away on all this surging sound, but back to the thornier issues for a moment.

Despite its beauty and power, Turandot is a prime example of Western culture’s fascination with the East and all that problems that entails. At the time of Puccini’s composition, orientalism was popping up in art, design and music.

But questions about whether it is still appropriate to stage what has been termed yellowface opera at this current moment surface for good reason.

As an older art form, opera isn’t exempt from questions about what is acceptable or appropriate. Every company, when choosing to stage Othello or Madama Butterfly, has to ask hard questions about the what it means to cast white performers to play people of colour.

The issue of white washing has also surfaced increasingly in film, with performers like Scarlett Johansson taking on Asian characters, and other actors turning down such roles. But in opera world it is even more complex due to a variety of factors, most notably a lack of diversity behind the scenes, not simply on stage. As a recent article in the Guardian pointed out there are a number of opportunities in creating a more diverse pool of not only performers, but also directors, producers, costume designers and stage managers.

You need only look to productions like Macbeth, a co-presentation of the PuSh Festival and the Vancouver Opera last winter to see what is possible.

But in spite of bold new staging and innovative work, opera is always under threat.

Opera companies around the world are forced to contend with a seemingly unending parade of problems — an aging audience, a plethora of other (less expensive) offerings, simulcasts that stream distant productions and, always, the essential oddity of the form itself. People singing their lungs out in a series of preposterous settings such as ancient Peking, a Parisian garret, a druid gathering, or a pharaoh’s tomb, seems increasingly strange to modern sensibilities.

Still, it persists.

Maybe because it is hard to compete with the sheer bodily thrill of live performance. The few moments in my life where I experienced genuine catharsis, the terrifying kind that happens when you lose all control, have only occurred during a real live opera. It is a decidedly curious feeling when the subconscious elephant bucks off the controlling monkey intellect and goes thundering off, trumpeting its emotion to the sky. There is a reason that audiences demanded 165 curtain calls for Pavarotti, or clapped for one hour and 20 minutes after Plácido Domingo’s performance of Othello on July 30, 1991.

As an adult, one can see the complex and harder questions, as well as your own complicity in loving something that is problematic. But as a child, none of this ever occurred to me. I loved the brutal magnificence of Turandot, and especially the woman at the centre of the story. An unrepentant creature who gets to traipse about in huge golden headpieces telling everyone to shut up, ordering her guards to kill whomever she doesn’t particularly like and possessing a beauty that drives men out of their minds with incendiary passion. She is every preteen girl’s fantasy come true.

Some efforts have been made to soften Turandot, to humanize her, but I will have none of it. I want her bigger than life, vicious, vengeful, generally badly behaved. And absolutely unpunished. My point is essentially that love is complicated, and it can make you do crazy things. And opera is nothing if not slightly crazy.

That is why we love it so. ![]()

Read more: Music

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: