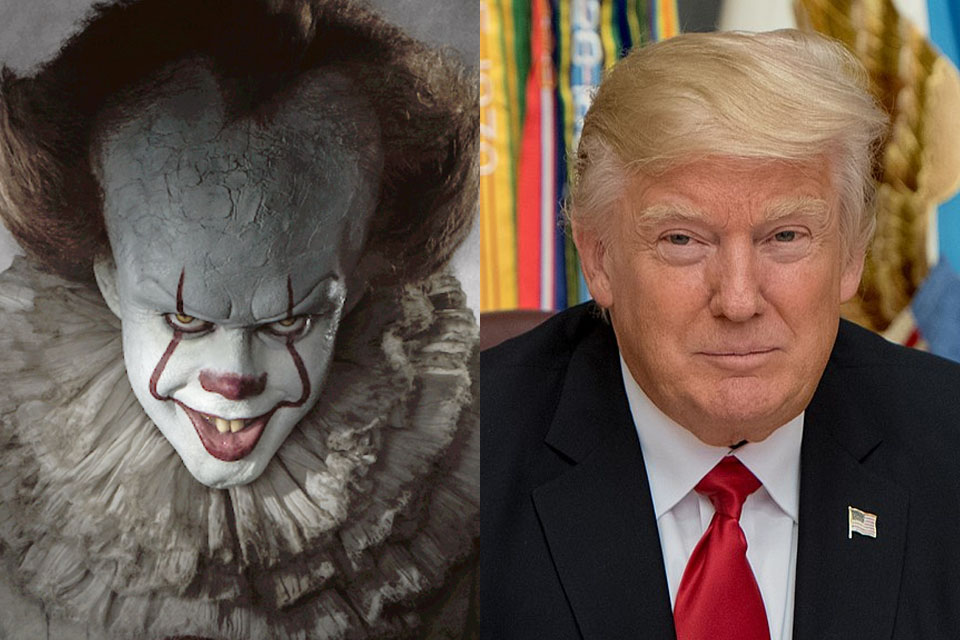

What is orange, and white, and evil all over? The most immediate response might be the orange clown sitting in the big white house in the U.S. capital. Another answer might be a shape-shifting space monster that emerges from the sewers every 27 years to eat children and cause a ruckus.

Both answers would be correct. But one is the terrible reality in which the world currently finds itself and the other is a little, light diversion from said terrible reality.

The cinematic adaptation of Stephen King’s bazillion page opus It arrived with some fanfare in theatres last week. The clowns were angry. The balloons were red. Things were tense. Meanwhile back in the real world, three separate super storms threatened to wipe out large sections of the coastal U.S., genocide was underway in Myanmar, and two pudgy megalomaniacs each had a plump hand poised over the nuclear button.

But what you should really be afraid of is clowns. Those pasty-faced jerks will really mess you up.

It is an interesting moment for the reemergence of old Pennywise, some 27 years after the television mini-series starring John-Boy Walton and Frank-N-Furter Tim Curry. But the clown has returned and not a moment too soon. Things haven’t looked this 1950s since the ‘50s. Lynching is back, racism has reared its fat white head like a witchetty grub, women are well on their way to barefoot and pregnant, and the orange and white man is in control. All of which should make King’s story of an evil entity named Pennywise, the Dancing Clown terrorizing a group of awkward preteens in rural Maine, somehow exactly the story we need in this instant in time.

Or so one would hope.

In director Andy Muschietti’s film, things start off with two boys on a rainy day. Georgie Denbrough and his old brother Bill are stuck inside on a long, wet afternoon. The light is bluish and drear. The world is drowning. In order to entertain his little brother, and get him out of his hair, Bill makes a paper boat, carefully sealing the vessel with paraffin and dubbing it the S.S. Georgie. A portrait of primary-coloured innocence, Georgie sets off in yellow slicker and green galoshes, chasing his boat down the sodden street until it disappears down a storm drain.

It is a proper introduction to time, place and the central actors of the story. It also leads nicely up to our first glimpse of Pennywise, a pair of feral yellow eyes, and a lipstick grin, crooning and drooling, thick ropes of saliva running like water off his chin. Any child raised on stranger danger would take one look and hightail it out of there, but not our wee Georgie, who decides to have a good old-fashioned chin wag with the clown. Things do not end well for Georgie. And so, it begins.

If you don’t remember the story, never fear, or perhaps do. The film trots out the members of the Losers’ Club (Bill Denbrough, Ben Hanscom, Beverly Marsh, Richie Tozier, Stan Uris, Mike Hanlon, and Eddie Kaspbrak), one by one, each with their respective cross to bear. Be it a missing brother, an incestuous father, an over-protective mother, or a mysterious quality that draws bullies like a dog whistle.

Things are not looking so super sweet in the small town of Derry, Maine. Aside from the fact that children disappear at twice the national average, a climate of misogyny, racism, and casual dislike of just about everything pervades the place like a fog. It is there in the bullies who run roughshod through the local high school. It leaches out in the pervy glances of older men. It creeps on giant clown shoes into the quiet streets and tidy neighbourhoods, leaving a trail of blood red balloons in its wake. The adults blither on in oblivious fashion, blind to the fact that Derry has a peculiar history of mass death every 30 odd years, or so. It is the kids, poised on the perilous edge of adolescence, who sniff It out.

All of this plays out in linear fashion, one character after another, introduced, given some motivation and then hustled into the main plotline of kill the clown and save the town.

It is unfortunate that the film is as diagrammatic as an algebra equation. Actually, I believe that algebra is more terrifying than old Pennywise. Certainly, the film pulls out all the stops. There are jump scares aplenty, and Pennywise draws the eye with ease. In all his ruched and ruffled glory, slicked with paint and sporting an orange quiff that the Donald would kill for, he looks, and acts the part — a capering, leering, tricksy wicksy portrait of evil. But the problem is that he simply isn’t that frightening, which begs the question of why?

In this fashion, it is interesting to look at film like It, and see what has been pared away. One is frog-marched through the plot, with nary a tary in the metaphysical hoodoo that King loves to indulge in. There are no world-making cosmic turtles, no Chüd rituals, and no pre-teen orgy — all of these things that were prominently featured in the book are gone, removed and replaced it with stuff you’ve seen a million times before. To be fair, the film is crisply made, handsome even, with attention paid to the details of sky and town. But a certain creeping blandness pervades the entire enterprise. For all its dedication to scaring your pants off, the film is deeply generic. The actors are just that. The sets are sets. “It’s just a movie,” as some wise soul noted.

I remember a first reading of the book being a decidedly dicey pleasure, of being so compelled and frightened, that I would read a few pages and then carefully put it down, wait a few moments to regain some control, before picking it up once more. But the film is drained of the creeping dread that suppurated through the pages of the novel. In its place is a tale of plain old vanilla goodness, dull as a puddle, defeating cartoon evil.

As a number of thoughtful critics have pointed out, this winnowing away of the political and social critique from the original story serves a particular function. Bilge Ebiri in The Village Voice has an especially good take on it, and the New Yorker as always hits the damn nail on its big fat head.

So, in good old Stephen King fashion, let’s get a little meta up in here. In the case of horror films, we look to screen as a site of expulsion, repudiation of the darkness inside, wrestling fear out into the light, where It can be dealt with. But when evil is already out in the open, and running the show, this mechanism doesn’t work in quite the same way anymore. In King’s story, it is the adults, with their ability to ignore the depravity in their midst, that are the most frightening. Your parents cannot save you, and sometimes they are the ones you should most fear. It doesn’t take too much extrapolation to extend this idea to world leaders and other forms of supposed authority.

The notion of evil battening on fear, central to the original story, requires a collective effort in order to defeat it. But the strangely enervating quality of the film offers up a different experience. It says, forget, or, maybe don’t pay attention to the real stuff, just be scared by clowns. Acceptance of the status quo is what allows evil to lumber along, popping up every so often to butcher a few folks, and then napping off its exertions. It is the diminution from big evil (“the universe is out of joint,” as the New Yorker article states) to manageable, acceptable evil that is the most horrifying thing. But even moral disgust may not be enough to stop the real clowns, who trip over themselves, in near-constant pratfalls of hypocrisy — a porno tweet here, a political gaffe there. It is funny and horrifying, ping ponging back and forth so rapidly between the two that a strange kind of motion sickness sets in. Eventually all you feel is slightly stupefied.

In order to compete with the real horror of the world, a film would have to do much more than Pennywise, reduced to a giggling figure, dancing about like his Dutch ruff is on fire. A fire at a nightclub, a bomb exploding, and everywhere missing kid posters papering the landscape — the most awful thing that happens in the film is that you realize that all these things have already happened in real life. Bombings, mass shootings, missing posters of people who simply vanished off the planet, atomized by the force of a planes hitting buildings. That stuff has been taken in, one horror supplanting the other, until your heart and mind can only accommodate so many, and your brain starts to chuck them out of your immediate memory to make way for the new material coming in.

A certain species of fear can really only exist in childhood and adolescence. It is dulled and blunted by adult life. But sometimes it comes creeping back in, from the side, and off to the left. As a child of the ‘80s, I remember thinking that the onset of adult life meant being constantly depressed, and obsessed with your failing relationships. Which as it turns out to be, wasn’t far off. But it also meant weirdly accepting the fact that nuclear annihilation was a foregone conclusion. The world would end in a ball of fire — it was just a matter of time.

It is this capitulation to a deeply familiar fear, and the odd passivity it engenders, that came back up in the film. When you wake up, and wonder what will the clown do today, grope some titties, tweet spelling mistakes to the world, or start a nuclear war, It becomes a bit too much to bear. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: