OK, I confess. I don't much like Star Wars.

Yes, I've seen the trilogy, but didn't bother with the prequels. At some point, I may see the new one (though after all the hype and online trailers, I feel I've sat through it 15 times). But the real force is awakening in new young writers, not in Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

The first one was pretty good in many ways: battered flying cars, Alec Guinness, some cool special effects. If you were a total science-fiction nerd in the 1970s, you could pick up countless witty references to the pulp magazines I'd grown up on, plus hommages that bordered on shoplifting to novels like Dune.

More literate critics missed much of that but picked up on George Lucas's use of Thomas Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which deals with the basic structures and images of mythmaking and storytelling. You could build a whole dissertation out of parsing the Star Wars franchise, and I'm sure many have.

If it had been a one-off, or even just a trilogy, it might have been a classic. Instead, it became both an industry and a culture of its own, now thriving well into its first half-century. And that was why I stopped enjoying it.

I should explain that in the 1940s and 50s, science fiction and fantasy were rather seedy branches of children's literature -- specifically, literature for boys in early adolescence. It was cheap entertainment, delivered in bulky magazines with lurid covers depicting spacecraft that looked like the automobile hood ornaments of the era, not to mention luscious white girls in brass brassieres.

A crude literature of sophisticated ideas

I loved it, and the wretchedly underpaid authors who wrote the stuff for two cents a word clearly loved it too. For all the ray guns and space pirates, science fiction was a literature of ideas, interpreting the speculations of scientists far more imaginative than the pulp authors like Edmond Hamilton and L. Ron Hubbard.

It was an exuberant, luxuriant ecosystem of ideas and stories, and I wallowed in it from the age of seven or so -- even in Mexico, where you could pick up a recent copy of Startling Stories or Thrilling Wonder for a peso or two in the Thieves' Market. Like so many readers, I tried writing science fiction, first in pencil and then on my mother's portable typewriter.

My stuff was imitation pulp, of course, but pulp fiction involved a well-plotted story and lots of action, and I imitated that as well. (Looking at some of my youthful efforts now, I'm appalled at how early I was locked into my fiction style.)

More importantly, it was an attempt to join a loud, eager conversation in which scores, if not hundreds, of writers were trying to out-think, out-smart, and out-weird one another: "You call that a time-travel paradox? Get a load of this!" "What if the ad agencies ran an overpopulated world?" One writer, Mack Reynolds, even imagined a future where cheap Russian consumer goods dominate the world economy; if he'd only picked China, he'd be regarded as a prophet.

As the baby boomers grew up in a world of sputniks and hydrogen bombs, science fiction became one way they dealt with it; fantasy, in which even gunpowder was rare, became another. The pulp magazines were driven out of business by TV and movies, but paperback novels began to appear on drugstore racks, offering wild ideas for 35 cents.

Clear-cutting the ecosystem

The 1960s presaged the clear-cutting of the science fiction and fantasy ecosystem. First, Star Trek appeared on TV. Second, the first paperback versions of The Lord of the Rings began to appear. Gene Roddenberry and J.R.R. Tolkien were doubtless geniuses, expressing remarkable personal visions based on the tritest of ideas.

For a vast mass audience, those visions became the only visions. It was as if the silly, squabbling Hobbits in the Shire had been acquired by Mordor in a hostile takeover. Artisanal science fiction and fantasy vanished; the iron age of industrial science fiction and fantasy had begun.

George Lucas's original 1977 Star Wars built on that industrial foundation, turning a pretty good movie into a blockbuster commercial for toys, lunch boxes, and general kitsch. That commercial has yet to end.

At about that time I was breaking into science fiction as yet another paperback writer (the Beatles wrote a song about us). In hindsight, I was lucky to get in when I did because publishers were looking for the next Tolkien or Roddenberry or Lucas, and they grubstaked a generation of new writers in hopes of another blockbuster.

They also grubstaked a generation of "sharecroppers" -- writers who gave up their own ideas to pump out spinoff novels set in the world of Star Trek or Star Wars, with the familiar characters in new adventures. And they funded a legion of Tolkien rip-off artists, some of whom are still cranking out ever more multi-volume sword and sorcery epics.

After a couple of novels with big advances, I kept writing, though for less and less money as my books failed to "earn out" those advances, much less make a profit for my publishers. I tried space opera, far-future sagas, levitating teenagers (a coincidental movie called The Boy Who Could Fly appeared just as my novel did, and killed it). I even tried fantasy until I couldn't look another dragon in the eye.

Not a blockbuster? Too bad

By the 1990s, I understood the new market far less than I'd understood the old one in the 1970s. And I pretty well packed it in after I'd spent four years writing a novel for an agent who returned it saying only, "No one here can think 'blockbuster' about it."

By then I could go into the science fiction and fantasy section of a bookstore, search the shelves for an hour, and leave empty-handed. The sharecroppers' Star Wars and Star Trek novels filled up too many of those shelves, and the rest were clogged with umpteen boring sequels to some groundbreaker like Frank Herbert's Dune or Isaac Asimov's Foundation.

I felt like some Amazonian forest dweller whose land has been cleared to graze cattle for the American hamburger market. A vast genre of popular literature had become mere franchises, like competing pizza chains. In the process, the franchisers had taught a generation of readers and viewers -- and writers! -- to prefer predictable sameness, not surprising variety. If it appeared at all, variety was just ever-bigger special effects, rendered by ever-bigger computers.

If I have any consolation, it's that the artisans are beginning to flourish again in the shadow of the franchises. God knows how they're finding publishers, but some astonishing writers are springing up like weeds among the cowpies.

Many are British: Charles Stross writes about interstellar travel as a pyramid scheme, and Dave Hutchinson's Fractured Europe novels look all too plausibly like the near future. China Miéville has gone beyond mere genre into a strange new realm of his own. Ian R. MacLeod's novels about the British industrial revolution (fuelled by magic, not coal) are powerfully vivid. Liu Cixin has single-handedly made China a science-fiction producer to reckon with.

Ursula's daughters

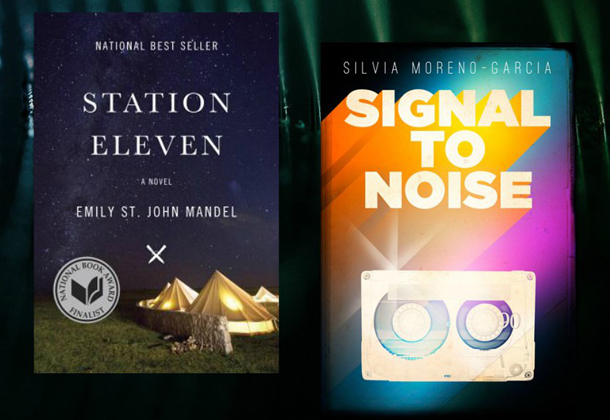

Even more encouragingly, many new writers are women. Aliette de Bodard, Franco-Vietnamese, writes beautifully about fallen angels ruling Paris and interstellar empires ruled by Vietnamese. Finnish writers Leena Krohn and Emmi Itäranta offer very different visions of very strange worlds. Here in Canada we have Emily St. John Mandel's acclaimed climate-fiction novel Station Eleven, and Vancouver's Silvia Moreno-Garcia, whose Signal to Noise evokes a 1980s Mexico City where teenagers cast magic spells on one another.

All are worthy daughters and grand-daughters of Ursula K. Le Guin, who's still writing superbly in her 80s, and I don't see a blockbuster in any of them, much less a franchise. They are too distinctive, too individual, and far too unpredictable.

Such writers, male and female, are gradually rebuilding the ecosystem I grew up in 60 years ago, but they're doing it better. They are better writers than the Asimovs and Hubbards, and they are deeper thinkers. Any of their books offer better company (and far more surprises) than the whole damn Star Wars series combined. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: