- Svend Robinson: A Life in Politics

- New Star Books (2013)

[Editor's note: Famous politicians, from time to time, make headlines for bizarre behaviour. Amidst the rush to detail the crash, the media can miss what may have caused the politician's perplexing self-destructiveness. So it was when Svend Robinson, the Burnaby NDP MP legendary for his righteous stands on issues ranging from gay rights to helping craft the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, admitted to stealing a ring worth five figures. That was in April 2004. Few at the time were aware that Robinson grew up in an abusive household, that he was suffering lingering effects from an injurious fall, or that he was battling a mental illness. A new biography, Svend Robinson: A Life in Politics by Graeme Truelove, details his struggles, triumphs and a contextualized account of the strange affair of the MP who grabbed for the ring. With permission from New Star Books, we reprint a slightly abridged version here. It starts with a fundraiser in Vancouver, featuring activist writer Noam Chomsky and NDP leader Jack Layton, that marked Svend Robinson's 25th year in politics.]

"How a guy who still looks 25 can have accomplished this is beyond me," Layton joked to the crowd. "I chalk it up to his shy, retiring nature."

The crowd laughed, and so did Robinson. Although they were there for Chomsky, they were there for Robinson, too. They knew only too well how far he had pushed the boundaries over the years, and how hard the boundaries had pushed back.

When Robinson took to the stage, more than 2,500 people rose to their feet. He felt a warmth that he hadn't felt in a long time as 25 years' worth of supporters applauded and cheered.

Still dark-haired, still lean, he crossed the stage and reached the podium in a few quick strides. Here, he was in his element. Imperceptibly, except to those who knew him best, he took one more half-second to appreciate the moment. Then he got to work. There was a long list of people to thank, from the volunteers in his first campaign to his current staff, who had flown to Vancouver that morning and were taking the red-eye back to Ottawa that night. Chomsky had to be honoured, of course. With the little time he had left for his remarks, Robinson addressed topical international concerns and then turned the podium over to Chomsky.

Following the famed professor's speech -- an indictment of increasing American hegemony and a call to arms to continued resistance -- Chomsky and Robinson shared the stage, while Robinson posed questions sent in by audience members. When the curtain fell two and a half hours later, Robinson eagerly headed into the crowd to greet the friends he hadn't seen in so long. The handshakes continued into the evening, and by the time he finally stepped back out into the cool Vancouver night, he was overwhelmed.

'Get Svend on this'

"I thought this was just who he was, and that he could keep it up forever," says Dan Fredrick, one of Svend's assistants in his last years in politics. "He always wanted to respond to everyone who wanted him to respond. You can imagine the number of issues over the years. He built up a huge number of supporters. Before I even knew very much about Canadian politics, I used to say -- almost like a joke, when I was talking to my friends -- if there was anything wrong, any injustice that I noticed in the world, I'd say, 'We should get Svend Robinson on this.' Because my understanding of Canadian politics was, Svend Robinson was a fighter for justice. This was before I was even really politically aware. But I think there are a lot of people out there in Canada, and internationally, even, who probably had a similar perception, one way or another -- that if something was wrong, let Svend know. And as a result, Svend became almost like this superhero for left-wing activists. And he wanted to, as much as possible, live up to that. It's unsustainable, I guess. He sustained it for a very long time, but I guess, ultimately, it was unsustainable."

On March 20, 2004, Svend stood before the sold-out audience at the Orpheum, chatting with Noam Chomsky and looking every inch a politician in the prime of his influence. But at home, in the first months of 2004, Svend's partner Max Riveron knew something was very wrong. Svend's sister Ingrid was in hospital with MS, nearly immobile and in constant pain, and it was devastating for Svend to watch his sister's condition deteriorate, knowing she probably didn't have long to live. Max had seen Svend under stress before, though, and the way he was behaving now wasn't normal.

"I was living with somebody different," Max recalls. "He was totally hyper. Like, extremely hyper. He wanted to change things constantly. Which he does, but it was just at a very high speed... he was making decisions by the second." He wasn't sleeping. He wasn't eating. He was travelling almost non-stop. He and Max were constantly fighting; anything could trigger an argument. And some of the things he was doing were outlandish to the point of terrifying. On Galiano Island, Svend was fiddling with the outboard motor to their boat and accidentally dropped it into the ocean. Max happened to go down to the dock and found Svend tying one end of a rope around his neck and the other end to a heavy rock he held, about to jump into the ocean to retrieve the motor. Svend might sometimes have been foolhardy, but he wasn't illogical. This was not Svend.

Max told him that enough was enough. He needed to leave politics and start taking care of himself. Svend ignored that advice, just as he had ignored the advice of his physician to see a psychiatrist after his hiking accident. The manic behaviour continued. On April 8, 2004, he flew to Kelowna to visit Ingrid. Alone with his thoughts that day, Max seriously considered leaving him. "Those days were really bad. I was ready to leave," Max says. "I just couldn't take it anymore. He was gone. Gone with the wind."

The next day, Good Friday, Svend took the early morning flight back from Kelowna. He picked up a copy of the Vancouver Sun, and during the flight he scoured the paper for the latest political news. He happened to notice an ad for a jewelry auction being held near the Vancouver airport. For some time he'd been thinking of proposing to Max with a diamond engagement ring and had already started visiting some Burnaby jewelers. Since he'd be at the airport anyway, he decided to stop by the auction on his way home.

After landing in Vancouver, Svend headed directly to the auction. He signed in, greeted the patrons who recognized him, and wandered over to look at the jewelry.

The RCMP would later value the large diamond ring at $21,500. Momentarily unattended -- except by the security cameras -- it sat on display on a glass counter, glittering.

Svend picked it up, put it in his pocket, looked up at the video camera and returned to his car. For a moment he just sat there. Then he realized he had left his cell phone on a seat in the auction house. He returned, sat down and watched for a few minutes as the auction continued. He returned to his car.

"And then I realized immediately, 'My God, what is this madness?'"

Good Friday torment

He knew he had to return the ring, but in that parking lot he felt something he rarely ever felt: fear. Too afraid to face the embarrassment of going back inside, he drove home. He tried to contact the auction house, but it was too late to reach anyone there. The head office was in Toronto, three time zones away, and it was Good Friday, after all. Still in a manic state, he spent the long weekend working at a frenzied pace. The day after the theft, he spoke at an Indo-Canadian celebration. At home, when he had nothing left to do, he went outside and started chopping wood. He was, by now, in hell. Tortured by shame, he fully understood the possible consequences of what he'd done, but what he couldn't understand was why he'd done it. His actions had gone against every principle he held dear. His identity was crumbling, and there seemed to be no explanation. As a teenager trapped in an abusive home, he had imagined what it would be like to kill himself. In the tormented days after the theft, he thought of suicide once again. But he wasn't a teenager anymore; he was a grown man, and one who had become used to taking responsibility for his actions.

Finally, on Monday morning, he got hold of the auction house and learned that the staff had already contacted the Richmond RCMP. Svend did the same and then spoke with Max.

"He said, 'I did it.' 'Did what?' And then he put his hand in his pocket and pulled out a ring. And I said, 'And what is that?' and then he said, 'I did it.' I said, 'Did what?' again. He said, 'I took it.' I said, 'What, that?' because I thought it was actually a drag queen's ring. It looked really pathetic to me. And then he repeated, 'I took it.' I said, 'You stole a ring? No, you must be kidding.' And he said, 'Yes, I did it. I'm on my way to the RCMP detachment, I've already phoned them,'" Max later recounted to Maclean's. "And he just left. And I cried. We spent that whole weekend together, and he never said a word, and I wish he would have."

After being interrogated by police, Svend phoned Clayton Ruby. "He was totally shocked and told me I shouldn't say anything. And I said, 'Well, Clay, I already have,'" Robinson recalls. Eventually the manic behaviour began to subside. In the next days, he sought psychiatric treatment and told the NDP leadership what had happened, so they wouldn't feel blindsided. He also met with his staff. "He took control, told us what happened and sounded sincere about how hard it was for him. We all expressed our surprise and sadness, and we moved on. That hardly took any time, and we all moved on to the next item on the agenda, which was 'What next? How do we deal with this?'" says Sonja van Dieen.

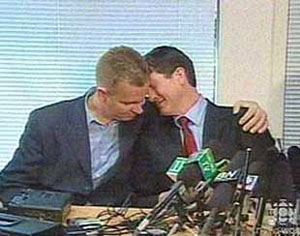

On April 15, flanked by Max, East Vancouver NDP MP Libby Davies and Burnaby-Douglas riding association president Doug Sigurdson, Svend held a press conference. Just as he had when he came out as a homosexual, he chose to make the news public himself. As he dropped the bombshell, he tried to offer an explanation:

"For some time now, I have been suffering from severe stress and emotional pain... The reasons for this are, of course, intensely personal, and I'm not prepared to discuss them, but among others, relate to the cumulative pressures of dealing with the emotional consequences of a nearly fatal hiking accident. The past few months have been particularly difficult and painful. This accumulated stress culminated last Friday, on Good Friday, in my engaging in an act that was totally inexplicable and unthinkable... I pocketed a piece of expensive jewelry. I did this, despite knowing full well that the employees who were there recognized me, and did so in a context where I'd provided them my full name and contact information in writing, and [knowing] that the entire area was under electronic surveillance. Something just snapped in this moment of total, utter irrationality...

"I will not seek to, in any way, avoid full responsibility for my actions...

"I have sought, and am receiving, professional medical help to understand and deal with these issues...

"Clearly, at this painful and difficult time, while there are outstanding legal and health issues to be addressed, I must devote my full energy and time to recovery and healing. I will therefore be taking time off for medical leave immediately. My hard-working and experienced staff, who have stood by me like the Rock of Gibraltar in this, will certainly continue to serve the needs of my constituents, and I will remain in close contact with them. I am also stepping down at this time as the federal New Democrat candidate for Burnaby-Douglas while these issues remain unresolved...

"As you can imagine, this has been a nightmare. I cannot believe that it has happened, but I am human and I have failed.

"I have felt such an incredible privilege and honour to serve my constituents here in Burnaby ... and I feel an equally strong sense of sadness that I have let so many people down."

Divided responses

"Our place looked like a flower shop," Max recalls. In the days following Svend's press conference, friends and supporters flooded their home with expressions of sympathy. Davies was as valuable a friend as he could have asked for. Jack Layton flew to Vancouver to be with him. Brian Mulroney and B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell called him personally. "From friends to enemies, they were there for him," Max says.

Svend wrote a letter of apology to the auction company; satisfied, they didn't intend to press charges. However, the opinions of a shocked public were predictably divided. "The 52-year-old New Democrat MP always has had a flair for the dramatic and a penchant for look-at-me stunts. But in my opinion this televised mea culpa topped them all," wrote columnist Ian Mulgrew in the Vancouver Sun. "He scheduled a news conference to choke out little more than, 'I won't run again if I'm behind bars'... his judgment was questionable in the past, it now can no longer be trusted in public office."

Several letters to the editor referred to Svend's "Academy Award-winning" performance at the press conference. Even Svend's sister Kim logged on to a conservative website, identified herself and urged that her brother be charged. His supporters, meanwhile, hoped for leniency. Their attitude was perhaps best expressed by letter-writer Mitch D'Kugener: "Mr. Robinson made a mistake on Friday, but it only proves what I was beginning to doubt: he is indeed human. I was beginning to think he was Superman."

If the Office of the Attorney-General had announced it was satisfied with Svend's apology, and that he wouldn't be charged, he might have run again. But no such announcement came, and he was left in limbo.

With an election call looming, Bill Siksay became the NDP candidate for Burnaby-Douglas, and Svend came to terms with the fact that his political career, for the time being, was over. "Oh, I felt terrible shame. Terrible shame. It was incredibly painful, even though people were so supportive and friendly. Everywhere I went, people would come up to me and say, 'We're really sorry about what happened, and we support you'... But every so often, somebody would say something nasty, like 'Watch out for your jewelry!' or something like that, and that just cut to the quick. It was very, very painful," Robinson says.

In mid-June an Alberta-based lobby group, run by publisher and former Reform Party activist Link Byfield, ran an ad in The Province which read, "Two months ago MP Svend Robinson was caught stealing. Will he be charged with theft?" With one week to go in the election campaign, Svend was charged. On August 6, 2004, he appeared in court and pled guilty to theft over $5000. Many prominent public figures wrote letters to the court attesting to his character. "I hope that one aberration in a truly good life does not compromise his future," wrote Stephen Lewis. David Suzuki wrote, "I believe at this time he deserves our gratitude for what he has done as a politician, our sympathy for the pressures he has lived with, and our compassion in meting out his sentence."

Svend had stood before a judge before, but the verdict delivered by Judge R.D. Fratkin was nothing like the politically charged admonishments he had heard in the past:

"I have been sitting here since approximately 9:30 this morning, some two hours and 15 minutes or so, listening to a gut-wrenching tale about a man who has achieved much more than most, and who has taken a fall, probably more than most, all for a bobble [sic], a trinket, a ring. The explanation is that what he did was an aberration, was a one-off, was as a result of enormous amounts of pressure placed on this man -- some of it self-imposed -- but primarily [by] people seeking his assistance as a member of Parliament, a significant position in this country. He, in his attempt to assist, has run himself ragged. There is evidence to support that proposition by the people who are near and dear to him, who made observations of changes in the man... His detractors really say that Mr. Robinson is nothing more, and nothing less, than a common thief who got caught, and who turned himself in, not because of conscience, but because that was the expedient thing to do... The sad fact is, there is nobody on this earth who knows what was in Mr. Robinson's mind, save and except Mr. Robinson... Shakespeare said that the evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones... He has fallen a long way. He has embarrassed himself, lost his opportunity to do that which he does and does well. Further, he is always going to be remembered for this. This is not going to go away. As I say, the public, at least in Canada, I think, has always lived by the sort of guiding principle [that] you don't kick somebody when they're down. Mr. Robinson's down. I do not think we need to kick him."

Fratkin sentenced him to 100 hours of community service and a year's probation, and ordered him to continue his psychiatric treatment. The conditional discharge, common for first-time offenders who had taken steps towards restitution, meant that he wouldn't have a criminal record. Asked today, Svend feels the sentence was fair, although Ruby suggests that the high profile of the case probably resulted in a harsher sentence than what a private citizen in similar circumstances might have faced.

Svend chose to perform his community service in Burnaby, taking care of injured animals and building habitats at the Wildlife Rescue Association of B.C. In an interview about a year and a half later, Ken MacQueen of Maclean's noted the symbolism of Svend learning to repair the wings of injured birds while he himself grew stronger.

'It just didn't make any sense'

Everyone wants to know why. It's the question that keeps coming up, in interviews with Svend's friends, colleagues and supporters, and in casual conversations with political junkies. Few doubt the sincerity of his tears at the press conference. But his explanation of what happened -- so lacking in details and a clear cause-and-effect rationale -- didn't provide the closure that supporters still crave.

The explanation was unsatisfactory because Svend himself was still grasping at straws, struggling to understand what had happened. "I just went back and forth, and over and over, and up and down, trying to think how this could happen. Two weeks after I'm riding high, celebrating 25 years with Noam Chomsky in a theatre full of people, I'm putting a ring into my pocket. It just didn't make any sense," he says.

Recalling his doctor's suggestion that he seek psychiatric treatment after his hiking accident, in his press conference he had hinted at the possibility of post-traumatic stress related to his fall. It was all he had to go on at the time. It's a reasonable supposition: according to the Canadian Mental Health Association, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may not surface until years after a traumatic event. Svend had shown several symptoms of the disorder, including insomnia and avoidance (evident in his refusal to seriously discuss the accident with a psychiatrist).

Although the theft had clearly been preceded by manic behaviour, Svend had recently been displaying an unusual lack of interest in elements of his work, another symptom of PTSD. "I was concerned that Svend wasn't himself for quite some time before the ring incident," recalls Doug Sigurdson. "I found him to be somewhat uninterested in functions of the executive committee, a trait he never showed before." Sonja van Dieen noticed the same thing. "I remember saying to him that I thought he'd been a bit off, that he'd been a bit less interested in the last couple months before the ring thing happened. Like maybe he was tired," she says.

PTSD can easily affect behaviour when triggered by other stressors, psychologist Paul Swingle explained to the Vancouver Sun after Svend's press conference. The same is true in the case of a brain injury, which Svend might easily have suffered in his 18-metre fall off a cliff. "Judgment can be affected in a serious way. The kind of behaviour he engaged in sounds like an impulse control issue," stated Swingle. "We get a lot of impulse control problems with patients with traumatic brain injury." Other psychologists interviewed by the Sun corroborated Swingle's explanation: PTSD or a brain injury could be responsible for such irrational decision making.

While the lingering effects of the hiking accident probably were factors in what Svend had done, in court Clayton Ruby offered another hypothesis. After decades of extraordinary stress, Svend had finally cracked under the pressure. That explanation, too, makes sense. That he was seriously overworked was no secret. Worse, during his career he had faced a level of vitriol from opponents that few politicians ever experience. He had even endured the wrath of caucus colleagues -- those he might have expected to be on his side. Friends suggest that those attacks hurt him far more than he ever let on. He had faced physical danger on the front lines of protests and in war zones. He had even faced it in his own home, due to the ever-present threat of homophobic violence. He had constantly been harangued with messages of obscene hatred and told that he was a sinner and a child-molester, condemned by God to an eternity in hell. On many occasions he'd wanted to leave the job, but something had always compelled him to stay. Unable to make the conscious decision to quit, perhaps he had subconsciously committed an act that would force his resignation and free him from a situation that had become impossible to maintain.

It's an assessment Jane Pepper finds reasonable. Because Svend felt he represented people who had no other voice, the pressures he faced were enormous. "I think the ring was the way to get the hell out when he couldn't get out any other way. To get out on his own -- somewhere in there, he would have thought that he was abandoning all those people," she says.

Bill Siksay retained Burnaby–Douglas for the NDP in the 2004 election and served three terms, developing an acute understanding of the pressures Svend faced. Like Svend, Siksay was known for taking positions outside the political mainstream, and he also developed a devoted following. "It's an incredibly hard job to get into, and it's an incredibly hard job to get out of," he says. "When you're somebody like Svend, and to a lesser extent me, when you're taking on things that other people aren't taking on, they're pretty desperate that you stick around to keep the work going. So there really is a lot of pressure to stay in the job, and to make the decision to leave is incredibly hard."

Perhaps Svend couldn't make that decision, so his subconscious made it for him. Such a hypothesis is possible, especially when Svend's troubled childhood is taken into account. According to Janet Woititz in Adult Children of Alcoholics, such behaviour is common among people with an alcoholic parent. "Saying no is extraordinarily difficult for you so you do more and more and more. You do not do it because you really have a bloated sense of yourself. You do it because you don't have a realistic sense of your capacity, or because if you say no you are afraid that they will find you out. They will find out that you are incompetent. The quality of the job does not seem to influence your feelings about yourself. So you take on more and more and more and more," Woititz writes. "Many super responsible people, in order to stop, have to get sick. It is the only way out and is very predictable. They give and give and take more upon themselves until they no longer have anything left, and they get sick. In effect, they burn out. They cannot find an acceptable way to stop short of this."

There is yet another possible explanation. After the theft, Svend began taking medication to help prevent the manic behaviour that had preceded his breakdown. His psychiatrist, Dr. Glen Freedman, diagnosed him with cyclothymic disorder, a specific form of what is commonly called bipolar disorder. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, cyclothymic disorder causes alternating periods of hypomania and depression, which could explain both the frenzied activity in the days leading up to the theft and the suicidal feelings after.

In an interview on CBC about a year after Good Friday, Svend revealed that he had a mental illness. He hoped that through this revelation he could help destigmatize mental illness, and at the same time offer his supporters a more complete explanation of what had happened. Still, it wasn't an easy thing for a politician to do. The opponents who had used his sexuality against him in the past would now be able to use his illness as well. "It was challenging, too, because I didn't want to make a direct link between mental illness and criminality either -- that mental illness, sort of, 'made me do it.' Maybe it did. I mean, it probably did. I don't know. Because it was irrational, it was ill," he says.

Of course, none of those explanations will satisfy the most cynical. For those inclined to believe the worst about him, the theft simply confirms what they already felt: that he was a self-interested, sleazy politician who, like so many others, was caught with his hands in the cookie jar. It's something Svend knows he has to address, and he is hard on himself. "Maybe, I mean, I saw this ring and thought that I could get away with it somehow. I don't know, right? I mean, I don't want to gild the lily in any way. Maybe there was just an element of bad in it, too. Maybe it wasn't just mental illness or post-traumatic stress or anything else. Maybe this was -- who knows? In all of us there's, you know, there's bad and good. Maybe this was bad. Maybe I just, you know -- temptation overcame me. I don't know," he says.

'Heroes are human'

The answer to the question everyone is asking is complex. PTSD, a possible brain injury, a cry for help, mental illness and old-fashioned temptation -- all were probably contributing factors. The answer is still unsatisfying to supporters, not because it is incomplete, but because they wish the answer were different. They wish it were clearer, easier to understand.

On April 18, 2004, three days after his press conference, Svend was supposed to receive a lifetime achievement award from the gay and lesbian newspaper Xtra! West. Still reeling from the events of the previous week, he didn't attend the ceremony, but organizers presented the award anyway. "Heroes aren't people who are perfect," presenter Aerlyn Weissman said. "Heroes aren't infallible. Heroes aren't unreachable icons who are somehow different from the rest of us. Heroes are people who stand up and speak out, when it's unpopular, when it's dangerous. And they mostly do it with the doubts and fears we all have when we do things that are hard. But they do it anyway. And they sometimes pay a very personal price.

"Svend Robinson is a hero. He will always be a hero to me. Because it isn't that heroes never fail in their goals, it's that they never fail in trying to achieve them. Heroes are human. They make mistakes, they get scared, and they need support, just as we all do."

Svend Robinson, now 57, lives with his partner Max Riveron in Geneva, and works for The Global Fund, an international NGO. ![]()

Read more: Politics, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: