- The Civil War in Color: A Photographic Reenactment of the War Between the States

- Sterling (2012)

I've long been struck by the colour photography of the Second World War, and even more by that of a New Deal program that sent photographers out into the U.S. countryside with colour film in their cameras, documenting the ordinary lives of rural and small-town dwellers from 1939-43. Somehow, seeing such long-ago scenes in colour made them far less remote.

Given the current level of computer manipulation of photographs, for years I've imagined converting the black-and-white photos of the Civil War to the colour photos now routine for war and everything else. So when I learned of this book, I had to see it.

It's an ambitious project, wisely subtitled a "reenactment," just as reenacted battles involve modern people dressed up in replicas of old uniforms. Formatted as a coffee-table book, it invites us to study the photos more as works of art than as history.

Quite apart from the quality of the book's colourized photos, it's made me think about the way technology acts as an intermediary between us and "reality." And it's also made me aware of how extensive colourization is becoming.

Shades of Grey

I grew up in a time when almost all photography was black-and-white, including the images of my childhood. The few colour photos from my infancy have faded; the blues and greens are gone, leaving red-and-black images of my impossibly young parents sitting with me on the running board of our old Packard.

From the first daguerreotypes to films like Schindler's List, shades of grey have filled our images of the past. But as Hollywood figured out colour, B&W changed from a technological necessity to an artistic statement -- not one that many modern audiences want to hear or see. The shift began as early as The Wizard of Oz, where the colour photography commented contemptuously on the B&W world of Kansas.

That same year, Gone With the Wind showed the world the Civil War in brilliant, powerful colours, and neither film nor history has ever been the same since.

As this book makes clear, our ancestors were delighted with early photography but equally aware of its limits. Stereo images were an early development. But the absence of colour was the big problem, and photographers tried to solve it. It invariably ended up being added to stubbornly B&W images.

Those early images even developed their own conventions, like tinting the sky blue with an orange horizon -- even when the photo showed an overcast rain-drenched city street. When Mathew Brady and others went onto the battlefields to record the Civil War, others were ready to tint what they came back with.

No, the results weren't very good, and the photography we know from that era is resolutely (and powerfully) black-and-white. As photography developed into a genuine art form and journalistic tool in the early 20th century, it advanced technically without using colour. And by the standards of an Edward Steichen or Ansel Adams, the images of Mathew Brady hold their own as masterpieces of composition. (He sometimes moved dead soldiers' bodies for just that reason.)

But Brady and other photographers of his era would have used colour photography if they'd had it, and their work would still be powerful and beautiful. The question with the present book is whether John Guntzelman's "photographic reenactment" of that work actually works.

Some of his effort is welcome, regardless -- he has cleaned up old negatives, removing scratches and blemishes like the digital cleanup routinely done for old recordings. Some colours, like those of uniforms, could be determined by checking surviving clothes and equipment. Others, like the hair colour of George Armstrong Custer, or Abraham Lincoln's complexion, required research into sources that often contradicted one another.

Many of Guntzelman's images are available online at Civil War in Color. Lincoln's dark complexion looks more "natural" than Custer's sallowness. Robert E. Lee looks almost airbrushed, while Stonewall Jackson bears a striking resemblance to the evil Kruger in the recent movie Elysium. Confederate uniforms, in grey or nondescript "butternut," look more real than the royal blue of Union uniforms. (How could the Yankees have won when they offered such visible targets?)

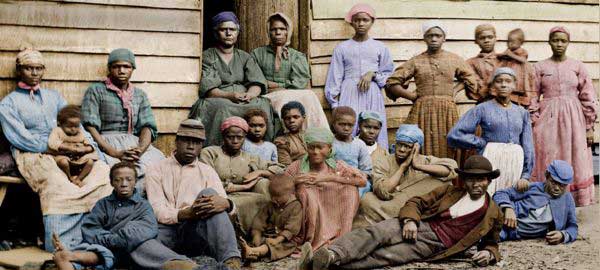

The images of black people seem vivid precisely because their clothing is so much duller than that of whites. A photograph of blacks digging up bones of the casualties of the Battle of Cold Harbor might have been taken in 1939, not 1865.

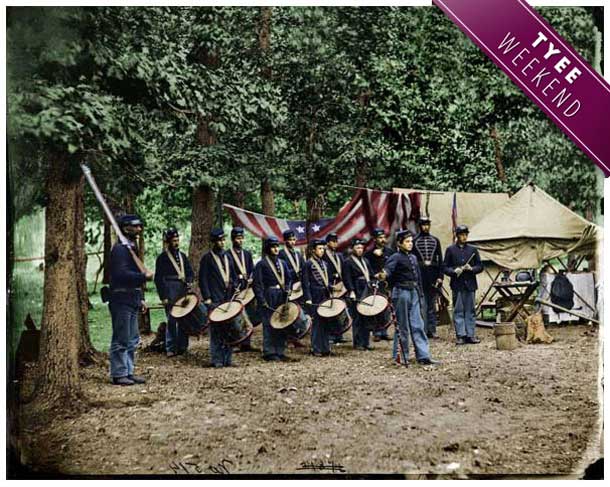

Other photographs taken in the open air also seem more real, like one of the drum corps of the 93rd New York Infantry -- a dozen or so boys posed against a U.S. flag with a backdrop of trees.

New perspectives on the past

In general, colourization does make the photos seem more contemporary, evoking some of the immediacy you can also see in a five-minute clip of colour film shot in 1927 London. But they are most successful when the flesh tones seem so real we wonder why this modern person is dressed in such a period costume. Too often, they seem either too pale or too bronzed.

By contrast, consider the astonishing colour photos of Russia before the First World War, taken by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky. His photos, digitally remastered, are far superior to most colourized B&W images, especially the flesh tones of his subjects.

Nevertheless, colourization is a remarkably active field, showing us many recent figures we know from contemporary colour as well as B&W images. Such images are often indistinguishable from the colour photos of the glossy magazines of the 1950s and '60s.

A Danish teenager, Mads Madsen ("Zuzah"), posts some remarkable work on his Colorized History blog, Facebook page and at deviantART gallery. His Civil War photos don't touch the scratches and defects in the negatives, but the colours seem more accurate than Guntzelman's; his Union uniforms are a somber navy blue.

Madsen also has a video tutorial showing how he colourizes an old photo, and a more detailed print tutorial explaining the process step by step.

We already use explicitly false colours in everything from Hubble telescope photos to images of viruses. Because we have little experience in B&W versions of such images, we don't object on esthetic grounds; the false colours can even be a "colour code" for what we're looking at.

In the case of old movies colourized for TV, we still have plenty of reasons to object; the colours seem as false as those of a virus, and they ruin photographic compositions that work beautifully in shades of grey.

But done right, the colourization of old photos can enhance that composition while also reminding us that Faulkner was right when he wrote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past." ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: