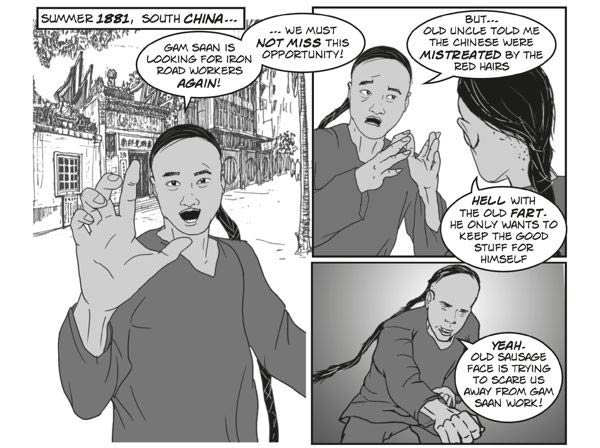

- Escape to Gold Mountain, A Graphic History of the Chinese in North America

- Arsenal Pulp Press (2013)

David Wong, a successful architect, was at the peak of his career when his father passed away in 1995. For years, Wong -- always preoccupied with building the "biggest, baddest" firm -- had put off fulfilling his dad's dream of visiting their ancestral village in China together. Suddenly, it was too late.

Wong wanted to make it up to his father by writing the story of his family. But slowly it became something much bigger.

Based on historical documents and interviews with elders, Escape to Gold Mountain, A Graphic History of the Chinese in North America, is the story of every immigrant and no one in particular. It is the collective story of the thousands of Chinese who came to North America over the past 100 years, making incredible sacrifices in order to give the next generation a better life. The novel was published last fall to outstanding reviews, and has gone through its third printing.

Wong sat down with The Tyee this past winter to discuss the novel, and the messages it conveys about the Chinese experience in North America and British Columbia. Here are excerpts from that interview.

Why did you choose the graphic novel format?

"I grew up in a very tough neighbourhood. Drawing cartoons was my way of staying out of trouble. But I got in trouble a lot. I was locked in my house to prevent me from making trouble.

"Because of that I wanted to be a cartoonist. Asian parents have this vision that you will become a professional. So I became an architect. But I never gave up on my youth. Even when I had an architectural firm we were doing animation. So when it comes to that question -- why did you decide to put it in graphic novel format? -- I was just waiting for the right opportunity.

"It came along about five years ago. I sold my firm to my partner, and I couldn't practice architecture for five years because I signed a non-competition agreement. So during that time I decided to follow one of my dreams to do a book."

How did you distill 100 years of history and thousands of stories into one book?

"It wasn't easy. I had a very good editor (Susan Safyen). She helped me focus my story... helped me balance the content. I had to pick and choose which stories would be most relevant, that would resonate the most with the reader.

"One of the stories I really wanted to convey across was the head tax, and the Exclusion Act, which was government or institutionalized racism dating back almost a hundred years ago.

"To many people, it's just a thing that happened, and it was a bad thing, and everyone says 'Okay, well now the Canadian government and the American government have apologized, and that's very nice.'

"But they don't realize that there are families attached to what had happened in the past; that what was more wrong was the tearing up of families.

"I had to convey a story which was based on a true story I heard from my grandmother, of family members who were separated because of these racist laws in Canada and also in the U.S. During the Second World War, when they tried to bring their family over to try to save them from what was happening during the war, they couldn't because both governments did not allow people of Chinese ancestry to come over here.

"So they were left behind in China and when the war happened, they were killed. And, you know, when you think about the man who was here, was essentially here working to send funds back to China to raise a family and hope for a better future for his family. All that work that this person did was all for nothing.

"At the end of the day, he lost his family anyway."

What can you tell us about the relationship between Chinese immigrants and First Nations?

"One of the things I tried to infuse into my book was the long history of the Chinese and Aboriginal peoples throughout North America. Many of the Chinese men married First Nations people, because there were no Chinese women here at the time.

"In my afterword, I talked about stories I heard as a young person, and how the very strong relations between the Chinese and First Nations was repeated again as an adult when I was doing my research up in the Cheam nation up by Hope and Chilliwack.

"They used to be very, very close and have a very harmonious, joyful relationship.

"I have a story here that talks about some rail workers who were injured and were left to die near Castlegar. The Aboriginal people took them in and nursed them to health.

"I have a very dear friend, his name is Leonard George from Tsleil-Waututh Nation. He said, 'Did you know, David, that the nation all the way up to the Rocky Mountains, they all have rice as a staple in their diet. And that was because some of the early miners and railway workers had this as a staple and introduced them to the Aboriginal people.'

"There was an exchange of sharing food, medicine and knowledge. That first wave of people developed interesting support for each other's community. I thought that was really, really cool. That history can go a long ways to help heal and things like that."

What are your hopes for the book as an educational tool?

"What I would like schools to do is to have the young ones look at this and then realize that all of them have ancestors who migrated from their place of origin to North America.

"For the young ones to essentially go back home and ask their parents and grandparents, 'Why did we leave our place of origin? Was it because of unrest or because of economic opportunities?'

"And then to understand why people migrate. What I want is for them to stop using their cell phones or computers and things like that and to start talking around the dinner table. I'm hoping it will be a catalyst to encourage family talks around the dinner table and then they'll share their stories with friends at school."

What has been the response from the Chinese community?

"My book tour down the West Coast was really an eye-opener for me, because I didn't know what to expect. I've never written a book before and I really have no clue what goes into these things.

"I found that the common theme going through everything was that this is what they all wanted for a long time. The folks who are most interested are multi-generational North Americans. Because the stories of nation-building are usually lost within the first two generations. A lot of young men and women actually died serving for Canada even though they were not recognized as citizens. They had to prove that they were actually loyal to this nation that didn't look at them as human beings.

"When I wrote this thing up and when I drew it up, it made it much easier to present to the new generation of young people. So they're very happy that it was presented in a format that can be well received by young ones. I've got lots of folks just coming up to me, thanking me."

How have others responded to the novel?

"Charlie Smith at the Georgia Straight forwarded me a letter to the editor from a person who said, 'Here we go again. The white guys are the bad guys pickin' on the poor Chinese, why's it always the white folks who are the racists?' And I didn't want to reply back, never did reply back, but my thought is that it's interesting to say that.

"For example, I was really upset when a lot of these folks from Hong Kong after Expo '86 were moving to Vancouver, and the first thing they did was cut down trees.

"[They said] they're cutting down trees because it's bad luck, it's a cultural thing -- you know, 'You're being a racist by saying you don't respect our feng shui...' -- things like that.

"This wonderful article came out in the New York Times... they interviewed a lady from the Dunbar and Kerrisdale Women's Committee, tree committee. Her name was Johanna Albrecht. She said, 'These people come into our city and chop down our trees. That's wrong. And we have to stop it. And if they call me a racist, then so be it.'

"When I read that article I called Johanna. 'Let me help you.'

"Because the way to stop this thing was to work from within, and shame them into not cutting down the trees. You have to give them a vested interest.

"We actually held a conference at city hall, had a rally there called Save our City. I went to the Chinese media and said, 'I bet the first thing you did on this hot summer day is park your car underneath a tree, so it gets some shade. And you talk about feng shui. I did my thesis on feng shui in university. The first concept of feng shui is embracing nature, and have the trees to block the wind. So don't give me this bullshit story about the feng shui being bad. You guys are cutting down trees because you're too damn lazy to look after it and you want a bigger house and the tree gets in the way. So call a spade a spade.'

"You fight racism not by saying that racism hurts, because it doesn't make any sense. But you show them the value of the culture of these things by letting both sides of the fence look at each other's perspectives.

"The wholesale embracing of multicultural society is a real double-edged sword. You tell people to accept and to be tolerant, but you don't really inform people why it's good for society to do that.

"I like the word diversity better [than multicultural], because it includes cultures, communities, partnerships; how people select their lifelong partners and things like that. That brings a lot of fresh ideas and knowledge. You get this engine of creativity and the innovation that comes from it.

"That's why I think the very positive thing about diversity is the sharing of ideas and of knowledge. That's what's really in it for humanity. If we really embrace this notion of acceptance then we can progress much quicker as a group." ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: