Not long ago, after seeing a trailer for the new remake of The Great Gatsby, I pulled my own copy from the shelf where it had sat untouched for close to 40 years.

It's the Scribner Library paperback, which I believe I must have bought as an undergraduate almost 55 years ago. The endpaper has a list of exam questions I wrote when I taught the book in some forgotten literature course circa 1970, and the book itself is full of my marginal notations -- guides to whatever my lectures were about.

Those lectures are as forgotten as the course. I have no idea what I told my students, and Gatsby itself was, on this re-reading, both a completely new book to me and one whose phrases and images had remained in memory for half a century.

It's also remarkable for being a young writer's book with an old man's wisdom. And like youth itself, it was probably wasted on me as both a student and a young teacher.

The Great Gatsby seems insubstantial: a string of parties and social meetings in the summer of 1922, stitched together with train trips and car rides between New York City and the Long Island suburbs of East and West Egg. Most of the characters are in their late 20s or early 30s, the last generation born in the 19th century but very much at home in the 20th. It deals with some love affairs, and a little violence. The story is just 182 pages long.

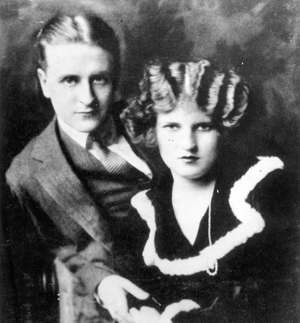

F. Scott Fitzgerald was just 29 when he published it in 1925, and already the famous author of two earlier novels and dozens of stories and articles. Toward the end of his short life (he died of heart failure in 1940, at 44), he regretted that he had not followedGatsby with a string of similar books. Instead he veered off into projects that took years (like Tender is the Night). Then, when they appeared in the 1930s, they seemed like warmed-over 1920s. Then he struggled to make money in Hollywood to support his insane wife in a sanitarium and to put their daughter through college.

An MRI scan of America

Actually, it's hard to imagine a novel that could have topped Gatsby. Scott Fitzgerald made The Great Gatsby into a kind of MRI scan of 1920s America, exposing countless social tumours and lesions that remain unhealed almost a century later.

His theme, as I read it now, is the American dream of social mobility -- a dream already hopelessly compromised. Nick Carraway is Midwest upper middle class, like Fitzgerald himself, a generation so confident of its coming success that Nick starts his narrative with his father's advice: "Whenever you feel like criticizing any one, just remember that all the people in this world haven't had the advantages that you've had."

Nick's generation has come home from war to a booming economy. Nick himself is in New York to get rich in the bond business rather than stay in the family hardware firm. He has been doing everything right: going to the right prep schools and university, making the right contacts, fighting in the war. Now he's ready to move up.

Gatsby, by contrast, has done everything wrong. He comes from a working-class background. He's exploited chance contacts with the wealthy to become wealthy himself, but on the wrong side of the law. He's met Nick's cousin Daisy, a southern belle, fallen in love with her, and then lost her to Tom Buchanan, old American money. He's made something of himself, in an ironic Horatio Alger way, but only so that he can win her back -- and thereby fulfill his version of the American dream.

In the summer of 1922, everyone is on the rise, and Nick doesn't always approve. He mentions driving across a bridge and being passed by a car with a white chauffeur and two well-dressed black men in the back. Gatsby's wealth is largely thanks to Meyer Wolfsheim: "A small, flat-nosed Jew raised his large head and regarded me with two fine growths of hair which luxuriated in either nostril." This, we learn, is "the man who fixed the World Series back in 1919."

Nick also takes the trouble to list those who attended Gatsby's parties, a brilliantly snobbish set piece that catalogues the range of social climbers:

"...From farther out on the Island came the Cheadles and the O.R.P. Schraders, and the Stonewall Jackson Abrams of Georgia, and the Fishguards and the Ripley Snells. Snell was there three days before he went to the penitentiary, so drunk out on the gravel drive that Mrs. Ulysses Swett's automobile ran over his right hand."

Women as symbols of victory

As for sexism, Nick's world takes it for granted. Women are almost a different species, more symbolic than real. That's why winning Daisy back is so important to Gatsby, who doesn't seem to have a clue who she is as a person. Nick, meanwhile, casually mentions a brief summertime affair that ends when the girl's brother threatens him. He also ditches the "small-breasted" tennis player Jordan Baker.

Clearly, social mobility has gone too far in 1920s America. Nick describes Tom Buchanan, the young millionaire, worrying about a junk-science book called "The Rising Tide of Color" that warns of the decline of the white race. The source of Tom's own family wealth is unmentioned, but is likely as dubious as Gatsby's. Nick feels as threatened by the Buchanan wealth as by that of the well-dressed blacks on the bridge and the freeloading parvenus at Gatsby's parties.

The movie versions of the novel have all emphasized the glamour of the characters and their time: the lovely clothes, the lovely furniture, the vast mansions. Judging from the trailers for the latest version, the glamour-meter has been cranked up beyond 11 through the magic of over-the-top art design, computer graphics and 3D.

Social mobility as horror fiction

But the novel itself shows only the horrifying tackiness of social mobility. Gatsby's mansion was built by another parvenu pretending to be a British lord of the manor. Wolfsheim admires Gatsby because "he's an Oggsford man." The books in the mansion library have been bought wholesale, their pages uncut and unread.

Nick commutes to work through an industrial wasteland he calls the valley of ashes. In that wasteland, the wife of a gas-station manager has become the girlfriend of Tom Buchanan, who one day drags Nick along on a sordid outing with her. The narrative of that afternoon and night in the aspiring lower middle class makes horror fiction look tame, though the only violence is in the moment when Tom breaks his girlfriend's nose.

Fitzgerald, an immensely successful young writer, achieved his generation's dream in the act of grasping its failure. Gatsby's vision of "the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us" was his own, but Fitzgerald already saw that vision turning to ashes and the blood in Gatsby's swimming pool.

The whole brief novel is a portrait of a nation duped by its own fantasies, and the movies made from it have only reinforced those fantasies with their emphasis on quaint fashions and expensive cars.

Fitzgerald understood what was happening, both to himself and to fiction. He saw literature in print being gradually destroyed by the "more glittering medium" of movies, and Hollywood has paid him the fatal compliment of loving him to death. Version after version of Gatsby has followed his plot and dialogue, but what lives on the page is invariably dead on the screen. All that glitters is not gold. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: