Some time ago I published an article about 10 novels that aspiring writers should avoid. It wasn't because they were bad -- most of them are modern classics -- but because their readable styles looked so easy that they might seduce a young writer into imitating them.

Other novels deserve reading by writers precisely because they can't be imitated. They can only show us how far a particular technique can be pushed, and it's up to us to understand and adapt that technique to our own work.

Here are 10 novels that taught me something about the craft and art of fiction.

1. Tristram Shandy, by Lawrence Sterne (1767). Written very early in the history of the English novel, this has been been justly called the first hypertext fiction -- but without the links. It is supposedly Tristram's autobiography. But with one digression after another, it ends with Tristram still unborn. The narrative seems like one damn thing after another, with no plot. But Sterne is playing games with time and memory that apprentices should also learn to play.

2. Wuthering Heights, by Emily Bronte (1847). Bronte wrote a love story so intense we'd all get radiation poisoning if she'd made Kathy or Heathcliff the narrator. Instead, the dim-witted Mr. Lockwood tells the story as he's been told it by Kathy's old servant. That's enough insulation to keep us safely distant from events while still believing in the lovers' passion for one another.

3. Bleak House, by Charles Dickens (1853). Apart from its other wonderful qualities, this is a story told from two utterly different points of view: a nameless omniscient narrator writing in the present tense, and the first-person account of Esther Summerson, recounting her childhood and youth. The nameless narrator gives us a stunning view of the whole society, from rigid aristocrats like Lord and Lady Dedlock to street urchins like Jo. Esther gives us a personal focus in the mind and personality of one of the most complex young women in literature. Everything meshes. And Dickens cranked this out in 20 monthly instalments, giving us all a lesson in meeting deadlines.

4. The Devil in the Flesh, by Raymond Radiguet (1923). Radiguet published this novel at age 20, and was dead months later from typhoid. His account of a teenage boy's affair with a soldier's wife during the First World War was a scandal, but his serene style offers hope to other young writers who want to write well (and boldly) on grown-up issues.

5. The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925). No one's written a better income-gap novel or a sharper critique of the American dream of social mobility. But that was over 80 years ago. Some young writer may yet write a comparable novel about the Buchanans' rotten-rich great-grandchildren, using a descendant of Nick Carraway's morally compromised outsider as the narrator.

6. The Sound and the Fury, by William Faulkner (1929). Autism hadn't even been defined when Faulkner wrote this literary equivalent of an Escher drawing. The narrative jumps back and forth in time, much of it a tale told by the "idiot" Benjy Compson, who makes no distinction between past and present. Idiot he may be, but he rules his family as absolutely as bigotry rules Yoknapatawpha County in Mississippi.

7. Johnny Got His Gun, by Dalton Trumbo (1939). Like Faulkner, Trumbo writes from the point of view of a severely damaged person cast loose in time. Joe Bonham, a First World War soldier, has lost his arms, legs and face. Deaf, blind, and mute, he's being kept alive as a medical curiosity. Yet he manages to distinguish between memory and present time, and to communicate with his caregivers. Any writer wanting to do a more ferocious anti-war novel will first have to spend time in Joe Bonham's mangled head.

8. 1984, by George Orwell (1949). Never mind Orwell's anti-totalitarianism. He understands the utopian genre he's working in, complete with the island world of Airstrip One, the importance of a document (Emmanuel Goldstein's Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism), and the moral significance of language (in his case, Newspeak). And note that Winston Smith is no tragic hero but a sucker being manipulated into a phony rebellion by O'Brien, just for the fun of destroying him. The moral: fiendishly ironic plots are the work of fiendishly intelligent writers.

9. Catch-22, by Joseph Heller (1961). The Second World War still enjoys a reputation as "The Good War," but Heller thought that was a crock. He showed us a world where only insanity could save your life, and where the Germans could outsource the bombing of your base to guys on your own side. The lesson for today's young writers: a truth universally acknowledged is overdue to have its ass kicked.

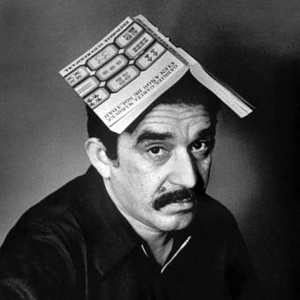

10. One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez (1967). Most autobiographical fiction is crap -- neither accurate memoir nor effective fiction. García Márquez transcended the genre by making whole generations of his family the subject of his novel. Then he co-opted his grandmother, who'd told him the family stories, and made her the omniscient narrator. She makes everything believable, from the historically accurate massacre of the striking banana workers to Remedios the Beauty's ascent to heaven. Outdoing García Márquez's magic realism would involve real magic, but a writer from a talkative, gossipy family might make Abbotsford or Gatineau as vivid and universal as Macondo.

Again, I'm not suggesting imitating these novels. As stories, they're as spellbinding as the sirens' song. But a writer who can pull back while still enjoying the spell can see how they work and perhaps apply the same techniques to a very different story. Odds are that most writers will still fail. But it will be a nobler failure than it might have been. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: