- Valley of Death: The Tragedy at Dien Bien Phu That Led America into the Vietnam War

- Random House (2010)

We were playing a little-boys' war game in a vacant lot next to my friend's house: having placed our toy soldiers in trenches, we were shelling the hell out of them with pebbles and dirt clods. An adult wandered out to take a look.

"What is this, Dien Bien Phu?" he asked.

We knew what he was talking about. Almost forgotten now, Dien Bien Phu was a battle in an unknown corner of the world that had every chance of spiralling into a third world war. It dominated the world news in the spring of 1954 as the Communist Vietminh methodically crushed 10,000 French paratroopers, Foreign Legionnaires and colonial troops.

Both the West and the Communists took the battle very seriously, though it was only one campaign in an anti-colonial war. And both sides understood that it really could get out of hand and turn global.

Reading this book disturbed me, because I can remember, more or less, what was going on in my life while Dien Bien Phu was under siege. A decade before it happened, the American war in Vietnam was clearly foreseen by the politicians in Washington, London and Beijing. No one wanted it. And despite their foresight, my generation -- American, Canadian, Australian, Vietnamese -- would be caught up in Indochina's Thirty Years' War.

It could have been a Thirty Days' War. World War II was winding down. The Americans, clear victors, had little time for the imperial pretensions of their British and French allies. President Roosevelt was open to the idea of an independent Vietnam; the French colonialists in Indochina had been collaborating with the Japanese throughout the war.

Cribbing from the Declaration of Independence

Ho Chi Minh, with American help, was already waging guerilla war against the Japanese and the French, and when Japan surrendered he was quick to take Hanoi and declare the Republic of Vietnam. He even cribbed his speech from the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

But Roosevelt was now dead, and Truman was more concerned about keeping France on the West's side of the Cold War. So he handed Indochina back to its former masters.

As Morgan's book makes clear, the British and Americans regarded the French as tiresome, high-maintenance allies who couldn't really pull their weight in the new world order. Rolling their eyes, the British and Americans provided the materiel and air support to let the French Army resume its prewar role in Indochina.

This was realpolitik at its most unrealistic, and it sealed the fates of perhaps a million Vietnamese children and 60,000 of their American and Canadian contemporaries. (The Canadians who went south to join the U.S. Army and fight in the war outnumbered the Americans who came north to escape it.)

By the summer of 1953, the French controlled little of their colony: Saigon, Hanoi and its port Haiphong, and the rice bowl of the Red River delta. In other regions it ruled by daylight and the Vietminh took over at night. Worse yet, the Vietminh were moving into Laos and Cambodia, also French possessions.

Imperialism undone

General Navarre, commanding French forces in Indochina, thought Dien Bien Phu would be a good chokepoint to keep the Vietminh out of Laos. It could also lure Vietminh General Vo Nguyen Giap into attacking the new base. That would take pressure off the Red River and give Navarre a chance to grind up the Communists. After all, in that remote and mountainous region the Vietminh couldn't bring in heavy artillery or supplies for a sustained assault. The French, however, could drop even tanks and trucks by parachute.

In hindsight, French racism undid French imperialism. They simply couldn't believe the Vietnamese were capable of organizing a major attack against a well-equipped army with air support and total air superiority.

Supplied and advised by the Chinese, Giap organized armies of coolies carried dismantled artillery on their backs, or on bicycles. When the French (and CIA contractors) bombed the roads from the Chinese border, the supply lines moved into a network of trails under the jungle canopy. Once the heavy guns arrived, the coolies and soldiers hid them in caves dug into the hillsides facing the valley of Dien Bien Phu and its scattered French strongpoints.

By late 1953, the French were surrounded. Thereafter, the Vietminh waged a war of grinding attrition that the isolated French could never win. Their airstrip was blown to fragments, trapping their wounded. Reinforcements had to parachute in, and were sometimes killed as they dropped.

Morgan's narrative focuses vividly and powerfully on the French combatants; the survivors wrote detailed accounts of their side of the fight. Giap's forces said much less, at least for publication, but they were clearly tough, well-trained, and ready to die. And they did.

Nuke Vietnam?

Meanwhile, the U.S., British and French governments were engaged in endless debate about what to do. Should U.S. troops go in? Could American air power make a difference? The use of atomic bombs was seriously debated until Eisenhower rejected the idea as militarily pointless and politically suicidal: using nuclear weapons twice in a decade against Asian enemies would discredit the U.S. for a generation or more.

Reluctantly, the western powers agreed to a conference in Geneva to end a war that the French were sick of. The Russians, Chinese and Vietnamese were there as well. Morgan effectively contrasts the political grandstanding and backstage bargaining with the carnage endured while the talks went on.

Eventually Geneva produced a temporary partition of Vietnam, to be followed by democratic elections in 1956. No one seriously expected the elections to be held (Ho Chi Minh would have won easily), but the settlement bought time for both sides. The Vietminh could rebuild. China was relieved that U.S. forces had been kept out of direct engagement in the war. France could turn its attention to another doomed war, trying to keep Algeria a colony.

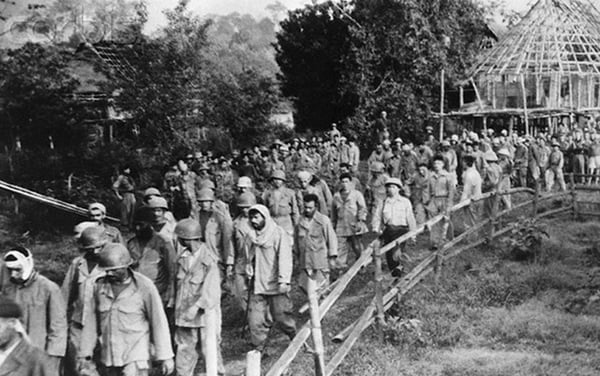

In the meantime, Dien Bien Phu had surrendered and the surviving soldiers had been marched long distances to prison camps. It was a death march comparable to Bataan.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this book is that the U.S. learned nothing from it and was itself at war in Vietnam a decade later. The Americans, like the French, pinned their hopes on anti-communist puppet governments, superior technology, and the empty threat of other Southeast Asian countries going communist if Ho Chi Minh wasn't stopped. When the puppet governments couldn't fight adequately, the U.S. threw in its own troops -- with results Eisenhower could have predicted.

So while my generation played war with toy soldiers in empty lots, our elders were setting up the conditions that would drive us into a real war. They had to have known what they were doing -- and yet they did it anyway.

The Vietnam war ended up costing the U.S. nearly 58,000 lives. The number of Vietnamese lives lost is estimated to be over a million.

Today, Aug. 4, marks the day in 1964 that Lyndon Johnson ordered the bombing of North Vietnam, steeply escalating the war's toll.

Tomorrow is the day in 1995 that U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher opened the U.S. embassy in Hanoi. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: