- Spook Country

- G.P. Putnam's Sons (2007)

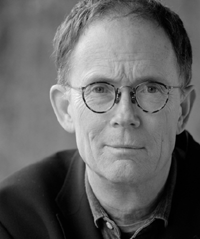

Just don't call William Gibson dystopian. The author of the cyberpunk classic Neuromancer, and eight novels since, admits his invented worlds aren't altogether pleasant places to imagine. But "someone stuck in Darfur right now might be happy to live in them. People who say I'm dystopian are middle class pussies!"

Gibson is loosening up this morning in his favourite noisy café on South Granville Street in his home city of Vancouver. He doesn't want to be called a futurist either, primarily because "I don't know what will happen in the future and I know that I don't know." Spook Country, his latest book, like Pattern Recognition, his previous one, is set in the current day, and gives us a post-9-11 America spooked by terror threats, manipulated by marketing, and mesmerized by digital artifice. As one of his characters declares, cyberspace is "everting," meaning that it is less a destination we choose, and more and more an environment that envelops us.

The plot is a knot from several threads: a Cuban/Chinese crime family in New York working a shadowy exchange, an ex-punk rock star exploring the limits of virtual reality art, and rumoured rogue arms traders on the high seas. Readers of Pattern Recognition will note the return of a creepy genius of advertising named Hubertus Bigend, who Gibson defends as "more Luciferian than Satanic."

After a grueling book tour, Gibson clearly is happy to be back home (and speaking tonight at the Vancouver International Writers' and Readers' Festival). Vancouver's essence, he says, is its young age, barely 100 years old. "Even 30 years ago, it was astonishingly thin on the ground." As a result, Vancouver is "sort of a video game," unencumbered by obsolete infrastructure that "you've got to repurpose. There's relatively little to repurpose here." And that, he likes.

During our conversation, here's what else Gibson had to say:

On being confused with being a 'futurist'

"The slot in culture that I'm most closely associated with is one in which charlatans declare that they know the future. My job is to sit near that slot and when people approach me I say: 'Only charlatans say they really know the future.' I sit near the tent where they give out bullshit and offer people a different sort of dialogue. My role is to raise questions."

On whether people will prefer life inside the screen to the real world

"I think that we're already there. And that is the nature of our experience of emergent technology and new media. A friend of mine was mining YouTube last month and he came up with footage shot in the street in New York on a particular day, in the evening. And he knew that this footage was shot the day before broadcast television began in New York. So this footage is of the last night that streets in New York were the way they were before everyone started staying home to watch television. All the footage that he's been able to find afterward is dramatically different. It changed. It changed the night they turned it on. The night they started to broadcast television in New York, New York ceased to be what it had been before. Because everyone stayed home to watch television.

"It's not that we prefer it, it's not even that conscious. It becomes the nature of our experience. If it's going to happen at all, it becomes the nature of our experience. If it doesn't happen it just becomes one of those iconic retro-future images."

On retro virtual reality

"There's some ironic stuff going on in Spook Country, for me anyway, around the virtual reality gear. Virtual reality was one of our most recent experiences of a future that didn't happen. The one before that would have been interactive television, on which millions of dollars were spent. Nobody wanted it. Nobody wanted it at all. But the Internet wasn't here yet, and people were saying, it would great if people could go back and forth with media, but it turns out the medium they wanted to do it with is one that presents the world, rather than a bunch of entertainment -- the Internet."

On the seamless net being woven

"There's some enormous number, millions and millions, of Iranians who are about to get their first cell phones. The infrastructure has been built. That's an interesting side of Iran we don't hear so much about. And you know, they're not just getting cell phones, they're getting Internet. What is that going to do to that country? The government is not going to be able to control what those people are watching. I just find that amazing, really.

"We've grown up thinking: 'Over here is the Internet, over there is cellular telephony, and here are iPods.' It's not going to be like that. That stuff is all just one cloud of stuff and it works together and you can't just get a little piece of it. The kids being born today will grow up finding the quaintest thing about the past was that people had these different devices that had discrete functions."

On whether we care less and less about what is authentic

"Doesn't that question imply an assumption it was different previously? And I'm not convinced of that. I think a lack of concern about virtual and real maybe telling us as much about what we used to call real as it is about what we now call virtual. I think that everything we've been doing since we sat around camp fires telling stories and started making cave paintings, everything we've been doing as a species seems to me to be part of this [desire and ability] to create prosthetic aspects of the self that are capable of surviving the death of the individual or indeed the death of an entire society. Other animals don't do that. And we've been doing it forever."

On how much 'new' is really old

"One of the things that I've found through whatever loosey goosey reading of human history I've managed through my life, is that very little is really new. You know, the Internet, for the first 25 years of its existence, has been almost exclusively text based. And so [people] are writing with frequency unseen since the Victorian heyday of the British Empire, when there were three mail deliveries a day, and people wrote and communicated constantly. We went back to it. It wasn't new. Very few things in the last 45 years have caused me to go 'Whoa! That's new!'"

On whether he enjoys conspiracy theories

"Conspiracy theories are popular because no matter what they posit, they are all actually comforting, because they all are models of radical simplicity. I think they appeal to the infantile part of us that likes to know what's going on."

On whether he believes 9-11 might have been an inside job

"Absolutely not. It makes no sense. I mean how could incompetents, particularly incompetent at keeping secrets, have done this? But that's a perfect example. People want to believe a simple version, a radically simplified, actually imbecilic version of complex and largely incomprehensible reality."

On whether some new terrorist attack will make 9-11 look small

"Eventually, I would say it's almost inevitable. Not immediately, because there is no need. The last one is still working. In some strange way, [for terrorists] anything that was less than 9-11 won't do. Anything less spectacular just won't do.

"How terrorism works in the broadest sense really is the inversion of the psychology of the lottery. The paradigms of asymmetrical warfare are such that one of the defining and unchanging characteristics of the terrorist is that he has very, very little in the way of stuff to work with. He can't really do much. He can kill a few people. He can knock down a few buildings in New York. But if he does it in a terroristically effective way, and if the society he does it to responds in what to the terrorist is the optimal way, everybody in society feels threatened. In spite of the fact that the odds of any given individual being done in by a terrorist's bomb are about the same odds of that individual winning the lottery.

"Terrorism is a con game. It doesn't always work. It depends on the society you are playing it on. It certainly has worked with the United States."

On why the 9-11 attacks 'worked'

"I think that if I were Osama Bin Laden, I can't really imagine what more I could ask for. The strafing of Mecca, possibly. But we've done everything we could wrong. It's not only America. It's like Thomas Kuhn's thinking on the structure of scientific revolutions, how we have these deeply held cultural paradigms, for instance about what we do when we are attacked. And we have these huge structures, armies and air forces and all of that, and they can be triggered by an event. But in this case, the event they were triggered by was a criminal act. It wasn't a military invasion of the island of Manhattan.

"But emotionally, I think it caused an understandable infantilization of society. Not just American society. I think there was a bubble right after 9-11 when the whole world seemed quite labile. Myself included. As we moved through that, all these existing mechanisms in our various societies moved forward to do what they believed they were there to do. Things that we sort of have in our immediate cultural mindset. What do we do when we are attacked? We invade countries. What do we do to countries that won't do what we want them to do? We use air power.

"Invade countries. Use air power. Well, it turns out, those are the two things not to do. The old paradigm is the wrong paradigm."

On the best way to fight terrorism

"The new paradigm is about degrading your opponent's trust networks. There would be a lot of money spent on training translators in Middle Eastern languages. So how is that going to play in Alabama. The people in Alabama are not going to be impressed and they aren't even going to know about it because it would all have to be done in secret.

"The assumption that the enemy is some sort of monolithic manifestation of whatever, that's also a losing assumption. Your enemy always consists of lots of different groups of people, and your first job, apart from deciding that those people are the enemy, is to start sorting them out and pitting them against one another. It worked in the Cold War."

On whether he is hopeful

"The present zeitgeist, now, is only one news cycle long. Something could happen tomorrow that would throw everything into a cocked hat."

William Gibson will be appearing at this year's Vancouver International Writers' and Readers' Festival tonight at 8 p.m. at "The Purpose of Fiction" with Liam Durcan, Claire Keegan, A.L. Kennedy and Alessandro Piperno; and on Friday October 19 at 8p.m. at "The Literary Cabaret" with Jacqueline Baker, Barry Callaghan, Sal Ferreras, Barbara Gowdy, Elizabeth Hay and Benjamin Zephaniah.