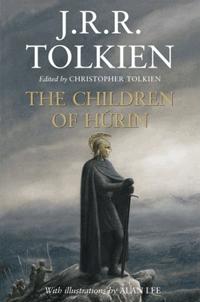

- The Children of Húrin

- (2007)

Over fifty years after the first publication of The Lord of the Rings, and over thirty since the death of J. R. R. Tolkien, his son has rescued another tale from the endless drafts and fragments that Tolkien left. It's a good occasion to consider not only The Children of Húrin but also the impact of Tolkien on our culture.

That impact has been slight in literary academia. Tolkien's reputation never entirely recovered from a scathing 1956 review of TLOTR by Edmund Wilson. The sheer popularity of the trilogy in the 1960s was another black mark against Tolkien: undergraduates were reading him against their professors, not for them, and finding more to enjoy there than in the canon of acceptable modern literature.

The popularity of The Hobbit and TLOTR persisted, culminating in the gigantic Peter Jackson film version that introduced millions to Middle Earth. By then, Tolkien's themes and images had saturated the culture.

Dozens of lesser writers cranked out imitations; fantasy became a literary industry, like romance novels. By the 1990s, teenagers with computers were bashing out their own Tolkienesque epics, just as I had on a typewriter in the summer of 1957.

Kids who didn't read still played Dungeons and Dragons. A human fossil, adult but very small, was found on Flores Island in Indonesia, and promptly named a "hobbit." Google "Tolkien" and you'll get over 21 million hits.

Homesick for Middle Earth

By now it would probably take a dozen dragons to guard all the treasure that Tolkien's imagination heaped up. His son, Christopher, editing his father's unpublished work, brought out The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, as well as a history of Middle Earth. These seemed to me disappointing: fragmentary, confusing, and lacking direction.

So when The Children of Húrin was announced, I wasn't sure I wanted to read it. It had been a long time since I'd read Tolkien carefully, and careless reading tends to bring up the flaws that Wilson jeered at long ago: "An overgrown fairy story, a philological curiosity."

Still, I recalled what an influence he had been on me when I was a boy, and how I'd dreamed of writing novels on his epic scale. Generations had grown up feeling homesick for Middle Earth, and I guess I was homesick too.

Well, you can indeed go home again, but you'd better expect the old place to look a lot different through adult eyes. It's not that Tolkien's world looks tacky or shabby -- quite the contrary. What once looked picturesque now seems harsh and unwelcoming, and we realize that Tolkien's view of his imagined world was a very bleak one.

The Children of Húrin is not even set in the green and pleasant lands of the Shire and Rivendell, but in Beleriand -- an enormous subcontinent doomed to sink beneath the sea in a struggle far greater than the war Frodo Baggins won. We are in the First Age, long before the Third Age of The Hobbits.

The Elves rule, with Men as their allies; both are locked in an endless war against Morgoth, a kind of corrupted god and the creator of the Orcs. (The social system and technology of the First Age survive almost unchanged into the Third Age. Middle Earth does not know, or welcome, progress.)

We don't see the climactic War of Wrath that will destroy Beleriand; we see only the struggle of one noble family against Morgoth's curse. It's a minor affair, but a familiar story: a young prince loses his rightful place, grows up in exile, and goes forth at last to wreak revenge against his usurping enemies.

Tolkien's epic roots

The curse of Tolkien's imitators is that Tolkien is all they've read; Tolkien himself read widely and deeply in ancient literature, and shaped its themes and language to his own ends. But he was no sheltered scholar; he began to create Middle Earth in the aftermath of World War I, where he had fought in the trenches and unaccountably survived.

It's no surprise, then, that Túrin, the hero of this novel, is a mighty warrior, a Beowulf capable of slaying dragons. But pride drives him from one disastrous decision to another, and his victories are hollow. Elves and Men love him and follow him, but regret it.

In a sense, Tolkien is satirizing medieval heroic romances just as Cervantes did in Don Quixote. But Tolkien finds little to laugh at in his own hero, and much to pity. It is tempting to read The Children of Húrin as one of the first novels of World War I, transposed into a different era but presaging the destruction of a great civilization.

Tolkien's style, however, is far from modern; Wilson called it "a story-book language," and it certainly is. Take a paragraph here and there, and it's easy to laugh at:

To Brethil three men only found their way back at last through Taur-nu-Fuin, an evil road; and when Glóredhel Haldor's daughter learned of the fall of Haldir she grieved and died.

The inverted word order, the strange names, even the cadence of the sentences, all seem pompous and overblown. We have been conditioned by a century of plainer prose, ever since Hemingway and the hard-boiled writers of the 1930s. But they had achieved their tough-guy tone by borrowing from the unemotional prose of the Icelandic sagas, and Tolkien knew those sagas better than most. His style is a direct descendant of the Icelanders'; Hemingway just married into the family.

So Tolkien says simply, "she grieved and died," without giving us the details of her grief or the manner of her death. He generally stays outside his characters' heads; again like the Icelanders, he shows us what they say and do, and lets us infer what their thoughts and feelings must be.

Edmund Wilson derided Tolkien's "travel-book" prose, but he missed the music of the names and the movement they give his sentences. This was always an attraction of TLOTR, especially for young readers who'd never encountered the cadences of the King James Bible. It's especially striking in The Children of Húrin. Reading it is like listening to a somber late 19th-century symphony from northern Europe: something by Grieg, or more likely Mahler.

Speaking with silence

In theory, we should be able to judge a book on its own terms even if we know nothing about its background or author. In practice, Tolkien's writing has troubled critics because it seems so unrelated to his combat experience and to his devout Catholicism.

Middle Earth in all its ages has no religion, no priesthood. The Valar, the gods who created the world and its peoples, have retreated to the forbidden West. Morgoth is a Lucifer, attempting to impose his will on stubbornly secular Men and Elves (and Dwarves). The Valar will intervene only to destroy him by destroying Beleriand. Six thousand years later, Morgoth's flunky Sauron will try the same thing and fail -- but this time thanks to the simple decency of The Hobbits and the courage of the other peoples of Middle Earth.

If Tolkien saw religion as his personal salvation, why did he not offer it to his characters and their world?

A good writer, like a good composer, can say as much with silence as with words and sounds. Tolkien's silence says that Middle Earth is a splendid but unhappy world because it has no real god.

That is certainly implicit in TLOTR, especially in the postwar sadness of Frodo. Not until he leaves Middle Earth for the home of the gods in the West does he find some hope of happiness. His companion Sam sees him off, and then returns to the Shire and the simple consolations of domestic life.

Tolkien's silence in this novel is even louder. Húrin's children, for all their high birth and prowess, destroy themselves in a brutal war. The best they can offer us, like the House of Atreus and like the ignorant armies of World War I, is a warning against self-deceiving pride.