- Fun Home

- Houghton Mifflin (2005)

- Bookstore Finder

The latest in breakout graphic novels is an unlikely candidate: a chronicle of its lesbian author's upbringing with her closeted, married dad, complete with side trips to the family business, the "fun home." "Fun" here is short for funeral, and it's an apt distillation of Vermont writer and illustrator Alison Bechdel's creative focus.

Bechdel has always been more than a little bit obsessive, as her jam-packed comic strips attest. For years she has penned a serial called Dykes to Watch Out For, in which a revolving cast of lesbians and their friends has grown up, gone out, gotten in trouble and otherwise represented our changing demographic.

Bechdel's strip continues to be popular -- it runs here in B.C. in gay and lesbian fortnightly Xtra West! -- for a couple of reasons. The comic's mordant take on current events still feels fresh, for one thing. Even if the characters aren't marching in protests, abandoning their cars on the freeway or otherwise ranting about America's suicidal policies, newspapers and televisions can be seen in the background trumpeting silly statistics or parroting nonsensical government rationales.

Fans also appreciate the fact that Bechdel is the furthest thing from a lesbian demagogue; she's catholic, in the best sense of the term. The strip's characters have tackled matters from gay marriage to cancer to lesbians who sleep with men (and get pregnant by and raise children with them, as it happens). As Bechdel presents them, these issues are real-life events rather than self-conscious representations.

The right-on lesbian parents of a child who decides as a preteen that she is a girl in a boy's body, for example, never have a conversation about What It All Means or Should We Let Him. Instead, they bicker and snipe in snatches, at her and at each other, in between trips to the park and minivan treks. The child in question can occasionally be glimpsed crossing the room, dressed as a princess or fairy. It's a lot like life as we know it.

A father's secret

Fun Home is both more and less than Bechdel's strip. The panels are larger and not quite so cluttered, and her stripped-down renditions of her childhood self are refreshing after the crammed, miniature canvas of Dykes. Still, it's an unavoidably claustrophobic story. Not only did her father purchase and painstakingly restore a decaying mansion, roping his three young children into cleaning the antiques and passing him the ball-peen hammer, but he did so in an extremely brief pair of cut-off shorts. The young Bechdel's babysitters were always teenage boys. Her father was an English teacher who recruited them from his own classroom, and Bechdel, even before she finds evidence in the form of moody, soft-focus nude portraits of the boys in hotel rooms she recognizes from family trips, is fairly certain he slept with them.

Skip this paragraph if you don't want to know the plot, but off at college, Bechdel recognizes her own sexuality, writing her parents a classic coming-out letter that is practically penned from between some woman's legs. Four months later, her father is clearing brush at one side of a two-lane highway and dumping it in the ditch across the way. A trucker sees the elder Bechdel leap backwards into the road. He is unable to avoid him.

The younger Bechdel, by now apprised of her father's secret and with a single, oblique letter from him as proof, is understandably tormented. She feels doubly cheated. Not only did she not know who her father was, but they never got to talk about their shared homosexuality.

'Meaning' sometimes intrudes

Parts of Fun Home feel forced, namely the narrator's insistence on linking her story to those of various Greek myths, American novels and classic plays, the last through her mother's avid participation in amateur theatricals. (That mother comes off a bit blank here: unsurprising, since she's still alive.) "My parents are most real to me in fictional terms," admits Bechdel, but the effect is of an unwillingness to let the story tell itself. Bechdel, understandably, looks for meaning: for readers, these heavy-handed allusions are unnecessary, and weaken the story.

The book has nevertheless struck a chord in places as diverse as People magazine and the New York Times Book Review. Plenty of reviews trot out the ubiquitous, and erroneous, notion that "graphic novels have grown up" -- an odd claim for a format that from its Xeroxed beginnings has tackled topics mainstream comics found too ickily realistic to acknowledge. The Times reviewer hopped in a car and went to see the small town of Bechdel's childhood. Everything is apparently as depicted. The family mansion is for sale, the reviewer reported, for a Vancouver-reasonable three hundred thousand dollars plus.

Bechdel's Fun Home was guaranteed a readership of Dykes to Watch Out For fans. But she professes surprise at the wider audience the book is reaching. If she had known how many people would take notice, Bechdel said recently, she would have been afraid to write so revealingly about her own family history. Bechdel is right to worry: the entire first printing of the book has sold out, and I worked hard to get my hands on a reading copy.

Before a largely lesbian audience in a Seattle women's bar in June, Bechdel appeared bemused by all the attention. Women who had probably been reading Dykes to Watch Out For for its entire run peppered her with increasingly personal questions. The author bore up under the strain, but the effort was apparent.

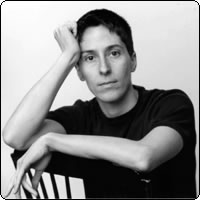

Bechdel has said that she is the model for Dykes regular Mo, a morose, androgynous type who bemoans the state of the world while sporting an eternal brush cut and a pair of wire-rimmed glasses, trendy circa 1992. In person, Bechdel has updated the stripey T-shirt to a blazer, but the brush cut remains. Her presentation of her obsessive, layered construction of single panels -- Bechdel creates photos of herself posing as every character before she draws the panels and researches historical photos for matters as small as a New York skyline circa 1976 -- was presented bashfully, as if she were wasting our time.

With Fun Home, as with anything Bechdel turns her hand to, exactly the opposite turns out to be the case.

Carellin Brooks is author of Every Inch a Woman: Phallic Possession, Femininity, and the Text (UBC Press) and an editor at New Star Books in Vancouver. ![]()