Hunter S. Thompson, on a visit to Montreal, once described an acquaintance as "bright and ambitious, but he is cursed with a dark and twisted curiosity that all too often characterizes Canadians."

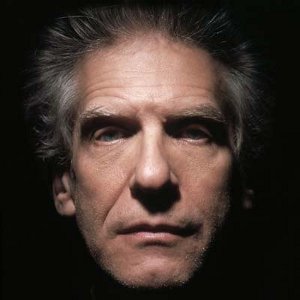

There could hardly be a better sketch of Canadian film director David Cronenberg. Curiosity has been the driving force in his auteurist career that spans six decades and has produced some of the most provocative films ever made. Almost a documentarian of his own imagination, Cronenberg has explored the mutated body and mind. His work is so distinctive that critics have coined the adjective "Cronenbergian."

One of the high points of his career came with his highly controversial film Crash (1996), about a subculture of people who fetishize car accidents and their byproducts. Cronenberg walked away from the Cannes film festival with a special jury prize for audacity.

Cronenberg's latest work, the psychological drama A Dangerous Method, is a beautifully-made, intelligent film, and has just been nominated for 11 Genies. But it won't win any prizes for audacity.

Cronenberg is definitely an auteurist director, and A Dangerous Method is definitely a Cronenberg film, with the classic Cronenberg protagonist, the scientific expert who is compromised by his own flaws. One of the director's earliest film concepts was Roger Pagan, gynecologist, about a neurotic man who impersonates a medical expert. In his current film, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung (played by Viggo Mortensen and Michael Fassbender, respectively) are echoes of the mad scientists at the centre of his earlier films, while Sabina Spielrien (Keira Knightley) is the patient-turned-analyst who inspires both men and catalyses their separation.

It's hardly surprising that Cronenberg would make a film about the founders of psychoanalysis, based on a non-fiction book by John Kerr and a play by Christopher Hamptom. These men showed us our interiority and our dividedness, precisely the territory that Cronenberg explores. A century later, we no longer grant Freud and Jung the status of rational investigators, and see them more as artists than scientists -- flawed men who encoded their own prejudices and unquestioned assumptions about their theories about human nature. A Dangerous Method is Cronenberg documenting his own intellectual ancestors, now that the Victorian ideal of the rationally-ordered mind producing a rationally-ordered world is crumbling all around us.

All three characters are well-drawn, beyond the superficial caricatures of popular understanding. Freud, keeper of the new rationalist hope that human nature can be perfected, has good reasons for dictating a new orthodoxy. Jung, his heir apparent, turns to ideas like telepathy and mysticism because to him these are the next step in studying human nature. Spielrien is Jung's patient, his protégé, his uncredited collaborator and his masochistic mistress, but she is her own person, with her own boundaries and agency.

Set in an idyllic view of the Edwardian years, before the devastation of the First World War, this is a world of reason, beauty and order that has hidden chaos waiting to erupt. There are definite Cronenbergian visuals too: Spielrein's neurotic contortions and stammers before her treatment, Jung using an Edwardian precursor to the polygraph on his wife, the sudden outbreaks of sickness, violence, sexuality and uncontrollable emotions. But there are few such moments. The mannered restraint the characters aspire to practice seems to inform the film itself. The beauty Cronenberg applies to the film actually works against his story, giving it the superficial nostalgic appeal of a Merchant Ivory costume drama, which can obscure the fact that the world of these people will be shattered in the coming decades.

Cronenberg's next project is Cosmopolis, an adaptation of Don DeLillo's novel about a billionaire cruising in his luxury stretch limo through the pandemonium of Midtown Manhattan. This is a neat inversion of the opening of A Dangerous Method, with Knightley as a screaming, convulsing wretch locked inside a horse-drawn carriage travelling through the beautiful, orderly countryside. What a difference a century makes.

The overall trajectory of Cronenberg's film career is relentlessly inwards, from devastated cities to devastated minds. He has moved through different film genres like horror, science fiction, psychological thriller, literary adaptation, gangster story and soft-core pornography, always doing his own unique take on those staples.

Cronenberg's roots are in the horror and exploitation genres of the 1970s, the generation of filmmakers fostered by Roger Corman. IMDB.com still describes him as the "King of Venereal Horror or the Baron of Blood" (quite unlike the affable film geek persona he presents in interviews). His first feature, Shivers (1975), is his unique take on the zombie/social collapse genre of Night of the Living Dead and The Crazies, with artificial aphrodisiac-parasites spreading through the inhabitants of a Montreal apartment complex and making them run amok. It was financed in part by the Canadian Film Development Corporation (later known as Telefilm), part of the effort to create a domestic Canadian film industry. Robert Fulford condemned Shivers in Saturday Night magazine, calling it "the most repulsive movie I've ever seen" and saying to Canadian taxpayers, "You should know how bad this film is. After all, you paid for it." (Actually, Shivers made money.)

His next feature, Rabid (1976) starred porn queen Marilyn Chambers as a woman with an experimental skin graft that turns her into a rabies-spreading quasi-vampire. Distributors, used to gothic vampire flicks, had no idea what to do with these films. Right from the beginning, Cronenberg defied genre and critical conventions.

The 1980s brought him into maturity, working with larger budgets and name stars. Better effects technology fostered his interest in the grotesque, but he also pursued his interest in the intimate relationships of his characters. The Fly (1986) and Dead Ringers (1988) are so affecting because Cronenberg takes us inside the relationships of their characters and makes us care about them, even as their lives disintegrate into madness and decay. As bizarre as the endings of those two films are, they are also breathtakingly sad.

A Dangerous Method can be seen as a reprise of Dead Ringers, which represents Cronenberg's transition from genre-film director with art-film leanings to art-film director with genre-film leanings. Loosely based on a true story, it stars Jeremy Irons as identical twin gynecologists who share work and women. When the subordinate twin falls for an infertile actress, the twins' already fragile equilibrium is irreparably disrupted. They spiral into co-dependency, drug abuse, paranoid delusions about "mutant women" and murder/suicide.

Since Dead Ringers, Cronenberg has employed fantastic elements in his films, such as the drug-induced hallucinations of talking cockroach-typewriters in Naked Lunch (1991) and the living video game consoles in eXistenZ (1999), but he's also moved towards what might be called psychological drama, with the strangeness emerging from the characters' flawed perceptions. Naked Lunch, M. Butterfly (1993) and Spider (2002) all feature men who prefer their own fantasies because they find living in reality intolerable.

Whereas his middle-period films ended with anarchy, exile and suicide, his later films have a slightly less pessimistic view: that an orderly life is possible, but it will always be punctuated by eruptions of chaos.

His gangster duology of A History of Violence (2005) and Eastern Promises (2007) contains no fantastic elements, but includes the same concerns of transformation and alienation. A Russian Mafia tattoo needle kit is a device of metamorphosis as potent as the telepods of The Fly, turning men into insects.

It would be a mistake to see Cronenberg's post-2000 films as an ashamed retreat from his grindhouse roots in science fiction and horror to more socially acceptable, highbrow genres like crime thriller and period costume stories. They have the same driving concerns: order collapsing into chaos, the flawed, divided man fragmenting, the desperate longing that can never be satisfied. These are explored in a less fantastic tone, but the weirdness is still there, lurking beneath the respectable trappings. No Merchant Ivory feature ever ended with Jeremy Irons committing suicide in kabuki makeup.

This raises the question of where Cronenberg fits in the culture today. The cinematic landscape has changed considerably over his career, even as he has moved through it. The rise of the "torture porn" genre, which Cronenberg foreshadowed in his Videodrome (1982), means there's an entire segment of the moving images industry built on shocking the bourgeoisie (and apparently some of the bourgeoisie lap it up).

However, Cronenberg has never been into shock for its own sake. Even in his earlier, more aggressive films, there was an intellectual aspect that went well beyond mere shock value. He employed a scalpel, not a cudgel, but he still wanted to make a lasting, almost physical impression on the viewer, to break through prejudices and defences.

Today, can Cronenberg still provoke us, or rather, does he still want to provoke us? The answer, it seems from A Dangerous Method, is no. There just isn't anything in the film that will push anybody outside their comfort zone. Some viewers will take it as just another corsets-and-Homburgs historical film.

This is not to say that Cronenberg should drop the costume drama and start shooting Canada's answer to The Human Centipede. In interviews, he has consistently argued that artists should be allowed creative freedom without the demands of commercial success or state control or critical approval. He has the right to make whatever kind of film he likes, even a sequel to his little-discussed drag racing melodrama, Fast Company (1979).

Yet, something has been lost. There's certainly no shortage of shocking movies out there, but how many of them get under the viewers' skin, or inspire the critical uproar of Dead Ringers or Crash? Cronenberg's unique position in the film world, one foot in Fangoria and the other in Cahiers du Cinema, allowed him to create a distinctive series of films, almost his own genre. The adjective "Cronenbergian" is rarely applied to anybody else's work.

To risk the critical faux pas of using the art to psychoanalyse the artist, A Dangerous Method could be read as Cronenberg questioning his own career in film. Is he like Freud, the rebel turned keeper of the new orthodoxy, or is he like Jung, the pioneer who needs to break from his own tradition to advance? Is it enough to show people their own sickness, or should he show people a way to be whole?

Cronenberg in his sixties now, and maturity brings changes in outlook. If he continues down the path of restraint, or just decides to retire, will anyone take his place as provocateur?

Provocation tends to be a young person's game. Maybe somewhere out there is a Jung to Cronenberg's Freud, some videographer toiling away in a low-culture media job, making commercials or reality TV or even torture porn. He or she is cursed with the same kind of dark and twisted curiosity, just waiting for the right circumstances to get that unique vision out into the world. This person will not be "the new Cronenberg," but will do the same thing: emerge from a despised genre and transcend it, to show us something we have never seen before, that will challenge us to call it horrifying or beautiful.

[Tags: Film.] ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: