Oakridge. Sen̓áḵw. And now Jericho Lands. The newest Vancouver proposals for high-density living break dramatically with the formula that made Vancouver high-density urban design admired worldwide. This is a conversation that needs to be moved out of the backrooms of city hall and developers’ offices, and into the light of public discourse. At stake is nothing less than the essential feel of this place Vancouverites call home.

I have long been an advocate for high density and missing-middle design. However, we seem to have migrated away from our winning strategy of creating a “space positive” civic realm. Let me explain what I mean by that.

When Vancouver’s urban design and centre-city renaissance took off in the 1980s, city planners and urban designers all adhered to an urban design consensus that went like this: “If we are to have high density areas, we must avoid the glaring failures of high-rise projects worldwide.” That failure had a name. It was called “tower in the park" design.

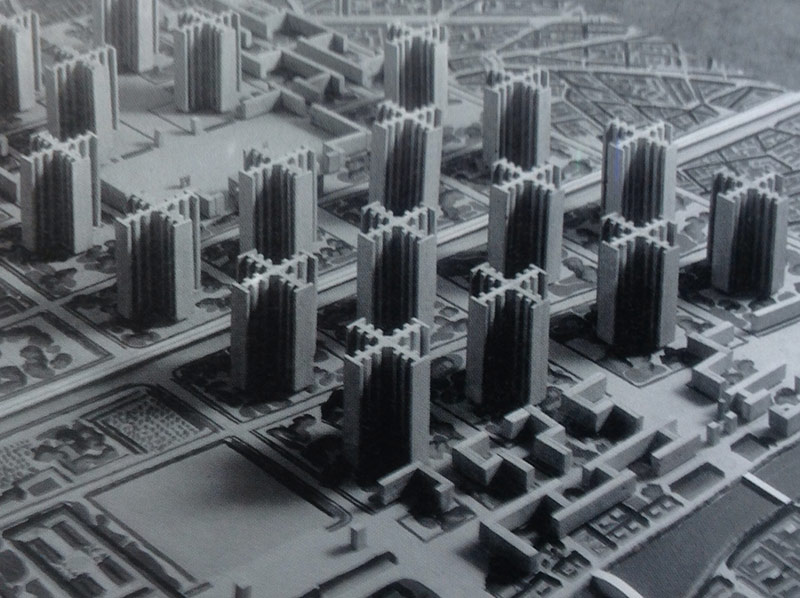

Tower in the park design was invented by Swiss French architect Le Corbusier, or Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, shortly after the First World War. His fame was spawned not by prolific built projects, but by his drawings and writings. They described a gleaming, (for the time) futuristic city of glistening glass towers set in a verdant landscape.

His aim was to free the city of its “congested streets and plazas.” In his time, cholera and tuberculosis were assumed to be caused by urban density. His solution? Spreading out buildings, while increasing their height enormously, to bring in light and air to all homes, and to surround each building with a carpet of green. In his most influential book, Radiant City, he famously called for “the Death of the Street”!

At the end of the Second World War, his vision became concrete in many places, such as newly built housing projects for the poor in the U.S., and high-rise developments to quickly supply housing in the devastated postwar urban landscapes of Eastern Europe.

Unfortunately, when actually implemented, the utopian dreams of Le Corbusier often failed to materialize. These “housing warehouses,” as they came to be known, turned out to be not such great places to live. The removal of low and mid-rise housing, and the streets that joined them into what we think of as “traditional city form” opened up previously unknown urban terrain where fear of crime could fester, and where citizens and police had a hard time controlling anti-social activities. Certainly, the tendency to concentrate just the poor in these segregated “housing projects” was a factor in their poor performance, but their design sure didn’t help matters.

By the late 1960s, many people became significantly disenchanted with the unbreakable allegiance of planners and architects to the Le Corbusier vision. The most notable critic was Jane Jacobs, whose 1964 masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, shook the world of urban design.

What an amazing event! Without a single picture or statistic, she thoroughly demolished all the arguments for Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, and showed, in simple language, how real people behaved in well-functioning and well-loved cities. She astutely celebrated buildings close to sidewalks, sidewalks full of people sipping drinks, streets framing distant vistas and buildings standing shoulder-to-shoulder to create “urban rooms” for civic life.

Zoom ahead to Vancouver in the 1980s, when this city’s second birth occurred post-Expo 86. Head city planners and trained architects Ray Spaxman and Larry Beasley were by now steeped in the ethos of urban design as creating active civic spaces — such as plazas, pedestrian streets and parks — built in ways that conformed with Jane Jacobs’ insights.

They worked with similarly inspired architects and urban designers to create “civic space positive” designs. This they did by either religiously reinforcing existing urban “street walls” (continuous street facing building facades) as in Yaletown, or by making new districts of spatially well-structured streets, plazas and parks as on the Concord Pacific lands.

So, for example, Pacific Boulevard is a classic of traditional urban space design, with its continuous "street wall" of towers set on "podium" bases. The bases of two to four storeys continuously hug the sidewalk, providing a steady rhythm of commercial storefronts. Upon the bases sit narrow residential towers held largely above the field of view along this grand concourse. Also note how David Lam Park and George Wainborn Park are both spatially contained by the building walls that edge it on three sides. This strong framing emphasizes the power of the dramatic view on the open fourth side across the waters of False Creek.

But these grand spectacles might obscure the more numerous smaller “space positive” gestures provided by planners and designers during this period. Notable examples might include Emery Barnes Park in Yaletown or Arbutus Greenway Park in Kitsilano.

Well, that was then, and this is now. The three major high-density urban design projects underway in Vancouver — Oakridge, Sen̓áḵw and most recently the Jericho Lands in Point Grey — all revert to “tower in the park” urban design principles. Each embraces the strategy of gaining green ground space in exchange for increases in building height.

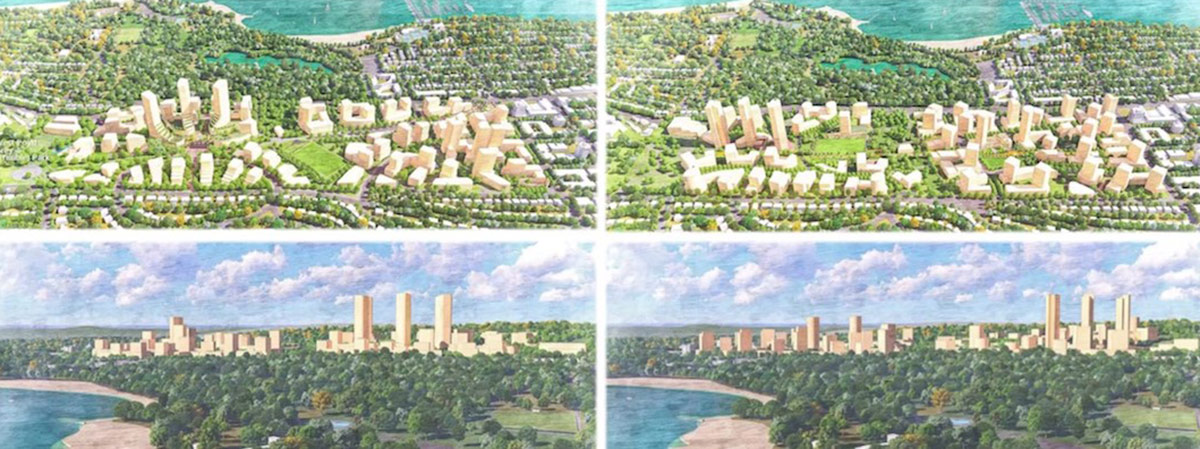

But aren’t tall spires the only way to achieve true density? Actually, it will probably surprise the reader that the actual density of the Jericho project is slightly lower than the density of Olympic Village at First Avenue and Manitoba Street, even though some of the proposed Jericho buildings are over 30 storeys tall and the majority over 15 storeys tall.

What? How can this be? After all, the plans for Jericho look like a tall building skyline, while Olympic Village is all mid-rise and buildings at Arbutus are all 12 storeys or (mostly) less?

The answer is that site density can stay the same as buildings get taller, if it opens up the ground plane. The recently revealed Jericho project in particular celebrates this strategy by touting its lavish percentage of green space, which of course comes at the cost of precedent-setting building heights.

I am among those who welcome a dense development built on the Jericho Lands. It’s a good thing to provide new and diverse housing options on Vancouver’s west side. Especially in a site so large, so close to open space amenities and well-served by transit and retail services. I am very pleased to learn that truly affordable housing is part of the proposed development, and await more details about how that ambition will be realized.

What I am firmly critical of, however, is the decision to achieve density by adopting something like Le Corbusier’s tower-in-the-park strategy. Versions of the same problematic approach are slated for Oakridge and Sen̓áḵw. (To be clear, Sen̓áḵw is within the city but not part of the city, nor does the city have planning authority over it.)

Here is what we forfeit as a result. We lose well contained civic street and urban plazas of the kind found in the Arbutus Walk and Olympic Village neighbourhoods. In fact, that formal strategy is entirely reversed at Jericho, Oakridge and Sen̓áḵw. There will be no “street wall” buildings providing “positive spaces” by adding integrity and clear form to new urban spaces. Instead, in all three developments, urban space flows indistinctly around the bases of tall buildings. Here it is the building forms that are “positive” and the urban space is consequently “negative” in this respect.

This prevents the sort of textured, lived experience by the city dweller that is difficult to communicate via drawings. Towers command imagination when illustrated via bird’s eye views and shown to rise above grassy spaces where happy people are penciled in. We should not be seduced by such dreamlike renderings. I am old enough to have watched this debate unfold over the decades, and to have seen the vision of Jane Jacobs prove far more hospitable to the ground level, daily experience of the city dweller than Le Corbusier’s.

Back to the question posed at the top. For those who live in Vancouver, how do we want our home to feel?

Quite aside from issues of affordability (which I have written about extensively in other contexts), I have always admired the “Vancouverism” strategy of doing high density right, conforming as it did with very “civic space positive” urban design rules.

I believe the international admiration of our high-density efforts, quite unlike the criticisms levelled at most high-density developments in other parts of the world, notably China, should not be abandoned for the fool’s gold of unformed green space and “green parsley” at the edges of overpoweringly tall buildings. We should not so easily take for granted the special feeling created by wide sidewalks with cafes and passersby to smile at.

It is a rule of thumb for adherents of Jane Jacobs’ theories that civic spaces that can only “explode” to produce a feeling of beauty in the viewer if those spaces have been contained by well-formed street walls, like walls in a theatre leading they eye towards the screen.

I argue that the design of the Jericho project would be much improved by using lower buildings in the model of Olympic Village. If I am right this would improve both the sociability of this new zone and enhance the drama of any large civic spaces created by architectural containment of street walls.

This shift could be achieved without loss of density because, as I have mentioned above, Olympic Village and the Jericho proposal are both at the same net density (in planner speak, at 2.5 FSR). My hope is that we consider, and reconsider, these civic space qualities as a new generation collaborates to build the 21st-century Vancouver. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: