After six weeks of political handwringing, $600 million, three debates, dozens of protests, hours-long voting lines and rising COVID-19 cases, the Canadian government ended up right where it was before the election: a Liberal minority government.

But what if Canada had a voting method different from first-past-the-post? Would the results have been the same?

Byron Weber Becker, who partners with Fair Vote Canada, an advocacy group for electoral reform, put those questions to the test. Right after the election, the computer science lecturer at the University of Waterloo hunkered down in his 25-square-foot basement office in Kitchener, Ontario, and ran a calculation using computer software he developed in 2015.

Becker fed the votes earned by each party, along with data from an Ipsos poll, into the program and allowed it to allot seats to parties based on proportional representation electoral systems.

In proportional representation systems, parliamentary seats are roughly apportioned to parties based on their vote share, making it easier for smaller parties with fewer votes to elect MPs. Similarly, it becomes harder for bigger parties to keep a stranglehold on the House of Commons, especially when they don’t enjoy a large portion of the popular vote.

Becker ran two simulations using two different approaches to proportional representation — single transferable vote and mixed member proportional representation.

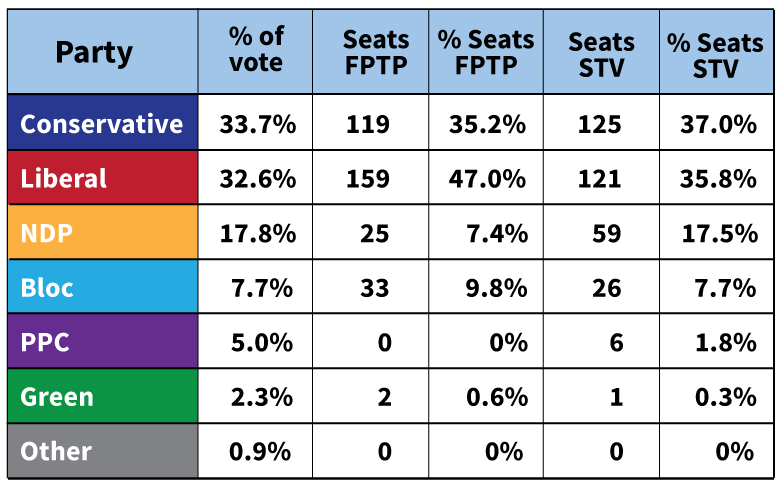

When the results were calculated using the single transferable vote method — which has voters rank their candidate in order of their preference rather than cast a vote for a single candidate — the Liberals, who nabbed 47 per cent of parliamentary seats with only 32.6 per cent of the popular vote, were now down to 35.8 per cent of seats. (Becker’s algorithm used the Ipsos poll to generate voters’ second and subsequent preferences.)

Using the same method, the Conservatives, who won 35.2 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons with a vote share of 33.7 per cent, were allotted 37 per cent of the seats by Becker’s algorithm. The NDP won 17.5 per cent of the seats, up from 7.4 per cent in the actual election, clinching a seat count proportional to their 17.8 per cent vote share.

However, in the simulated results, the gap between the Green party’s vote share and the seat count widened. Their seats dropped to 0.3 per cent from 0.6 per cent even as the party captured 2.3 per cent of the popular vote.

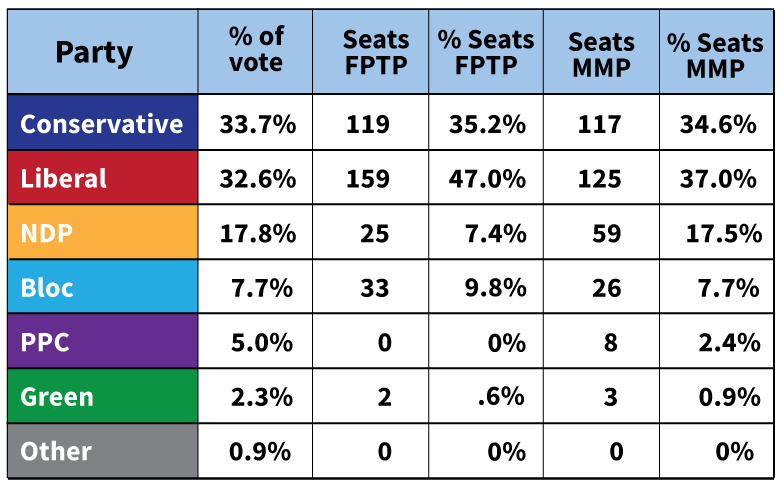

Using mixed member proportional representation, which incorporates both first-past-the-post and proportional representation techniques, the Liberals were the winners, although their seat count was more reflective of their vote share. The Conservatives closed in at 2.4 per cent behind the Liberals. And the rest of the parties, too, won seats according to the popular vote.

In this case, although the PR system closely reflected the votes of the public, the outcome likely would have been the same as the actual election: a Liberal minority government.

“Any proportional system is so much better than first-past-the-post,” Becker said.

Cara Camcastle, who teaches political science at Simon Fraser University, echoed Becker’s views, saying proportional representation is a better choice for democracy. “Proportional representation means that we would have every vote count, and then the seats would reflect the popular votes,” Camcastle said.

One of the outcomes of Becker’s simulations has been giving some people pause: what happens when far-right parties win seats?

The People’s Party of Canada, known for its xenophobic and populist platforms, failed to win a seat in the federal election even as it received five per cent of the vote. The party’s 2021 platform promised to relax gun control legislation, cut public spending and taxes, stop all funding promoting multiculturalism and drastically cut immigration, saying current policies “forcibly change the cultural character and social fabric of our country.” The party also said it intended to limit the definition of hate speech to expressions that “explicitly advocates the use of force against identifiable groups or persons.”

As hospitals were reeling from rising COVID-19 cases, many of the party’s candidates led or took part in anti-vax rallies outside hospitals and clinics.

Becker’s simulation found the party would win six to eight seats under proportional representation, depending on the system used.

The pros and cons of pro rep

The drive for adopting proportional representation has been around for a century in Canada. In 1921, the Liberals ran a campaign under leader Mackenzie King, who was a fervent advocate for the cause. Once in power, it established an all-party committee to study the issue — only to abandon it later. This became a pattern: several task forces have since been set up, politicians and experts have studied and deliberated and the government in power has upheld the status quo.

In 2015, Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau promised prospective voters it would be the last time Canadians voted using first-past-the-post. In 2016, after the party won the election, it formed an electoral reform committee. A few months later, the committee released a report supporting a proportional representation system.

However, the Liberals called the committee’s recommendations “rushed” and “radical” and set them aside in early 2017.

Provincial governments including Ontario, B.C. and Quebec have held referendums in which citizens were given the chance to vote for a proportional representation system. Support for change never reached the required threshold, though single transferable vote received 58-per-cent support in B.C. in 2005 — two per cent shy of the votes required to adopt it.

While there are several kinds of proportional representation voting systems, the focus has been on two types in Canada: single transferable vote and mixed member proportional representation, both of which were used in Becker’s simulations.

In the STV system, which is used by countries such as Ireland and Malta, each district elects several candidates instead of a single member. For a candidate to get elected, they must cross a threshold of minimum votes, which is calculated by dividing the number of voters by the number of seats to be filled.

Voters are asked to rank candidates in the order of their preference rather than cast a single vote. When votes are counted, the system considers the first preference of all voters. If all seats aren’t filled by candidates who meet the threshold, the candidate with the lowest number of votes is eliminated. Their votes are then transferred to the second preference of those voters. The process is repeated until all the seats are filled.

In mixed member proportional, which is used by countries such as Germany and New Zealand, voters are asked to cast two votes: one for their local candidate of choice and the other for their preferred party. Half the candidates are selected from single-member plurality contests, similar to the first-past-the-post system. The rest are added to the legislature according to the proportion of votes every party receives, minus the number of candidates from their party who got elected in the district elections.

Nora Loreto, a writer and host of the podcast Sandy and Nora Talk Politics, believes mixed member proportional combines the “best of both worlds,” as it allows citizens to vote for their party and their local representative. The system yields better citizen participation, Loreto added.

“You would have a situation where people, I think, would be encouraged on two planes. One would be to vote for a party. And so that party discussion is: here’s the leader; do you like the leader? Here’s the program; do you like the program? And second, do you like your local representatives?” Loreto said. “I think it opens things up quite a lot, because it allows you to then vote twice. It allows you to perhaps vote differently at the party level versus the local representatives.”

Better citizen participation also translates into stronger voter turnout. In the first-past-the-post system, if a party’s vote share in a particular riding is too low to offer any hope of winning a seat, would-be voters for that party may be discouraged from voting at all.

In a proportional representation system, Camcastle told The Tyee, “every vote would count.”

Emboldening the far-right?

Camcastle told The Tyee that Becker’s simulation doesn’t tell the full story about proportional representation and the People’s Party. Many systems set a minimum share of votes required before a party is awarded seats.

“A threshold would limit the influence of such fringe parties,” Camcastle said.

Becker’s system did not use a threshold for the distribution of seats since they vary. “It could be five per cent. It could be seven per cent, or it could be 20 per cent. And to be frank, at the time I didn’t want to have to deal with figuring out how to how to choose that threshold,” Becker said.

Camcastle said there are other things to consider, as voting behaviour changes with the voting method. Proportional representation systems drastically reduce strategic voting, for example.

Proportional representation systems also often lead to coalition governments, where parties must co-operate in order to form government and pass legislation. Parties may be compelled to moderate their positions in order to be a part of a coalition, Camcastle said.

Such a situation may also encourage parties to be less antagonistic, since “you don’t want to be slinging all sorts of mud at the candidate whose voters have listed you as their second choice,” Becker added.

Proponents of the proportional representation voting systems in New Zealand further argue that the method may also give a boost to candidates from traditionally underrepresented communities.

Despite the benefits of proportional representation systems, various governments have avoided adopting them in Canada, Camcastle said. “It’s beneficial for them to remain with the status quo.

“Once they get in power and they become the governing party, they want to reign, and so PR would change that,” she added. “If we had a different electoral system, we might have a different government right now.”

Not everyone is an uncritical fan of proportional representation. Richard Johnston, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of British Columbia, believes proportional representation produces “more diffuse coalitions and more opportunity for avoiding responsibility.”

"Advocates of PR tend to think of elections as only about as exact as possible a representation of bodies of opinion that are distinct-ish from each other,” said Johnston, who was also on the advisory board for the 2004 BC Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform and voted for a proportional representation system in B.C.'s 2005 electoral referendum.

“They don’t spend so much time on the question of who shall govern, what kinds of interests those governments incorporated in their deliberation, and to what extent are they called to account?”

As for Becker, the projections he calculated in partnership with Fair Vote Canada last week are just two of the many simulations he’s worked on over the years. When he’s not teaching or absorbed in other academic projects, he imagines different electoral scenarios and fuels his curiosity by running his algorithm and finding out the results.

His website is filled with graphs and statistics that estimate how shifts in voter behaviour would affect election results and how different proportional representation systems would have a role to play in that. For more than a year, Becker has also been involved in a court case that challenges the constitutionality of the first-past-the-post system.

Becker remains optimistic that some form of proportional representation may yet be instated in Canada. “We’ve been at this for a long time, but more people than ever are talking about it,” Becker said. “I think it’s going to come — not in a year or two, but within the next decade.”

Until then, he said, he will keep crunching out numbers and beavering away. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Election 2021

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: