For years thousands of residents of co-ops in Vancouver have been left to nervously wonder what would happen to them when their leases run out. Many are coming due within ten years and some as soon as next year. Would the city renew those leases, and if so under what terms? A particular locus of anxiety has been False Creek South, home to the second highest concentration of co-ops in the city (Champlain Heights is first).

Well now the proposed answer by city staff is available for all to see and comment upon. In short, it recommends the city charge a good deal more for renewed leases to co-ops, redevelop a bunch of them to also include dense, non-co-op housing, and give subsidies to people whose rents have been made unaffordable. The new money the city gets from jacking up rents and redeveloping will go to pay for other affordable housing options, says the document.

Council has had very little time to digest the 50-page Methodology for Co-operative Housing Lease Renewals before today’s meeting, when staff is recommending it be accepted. Residents are invited to speak at the session. Such short notice for weighing so complex a document is unfortunate. Here are some concerns that deserve a thorough airing. Let’s hope councillors and citizens raise and debate these questions:

Will this pave the way for transforming False Creek South into highrises and far more market housing?

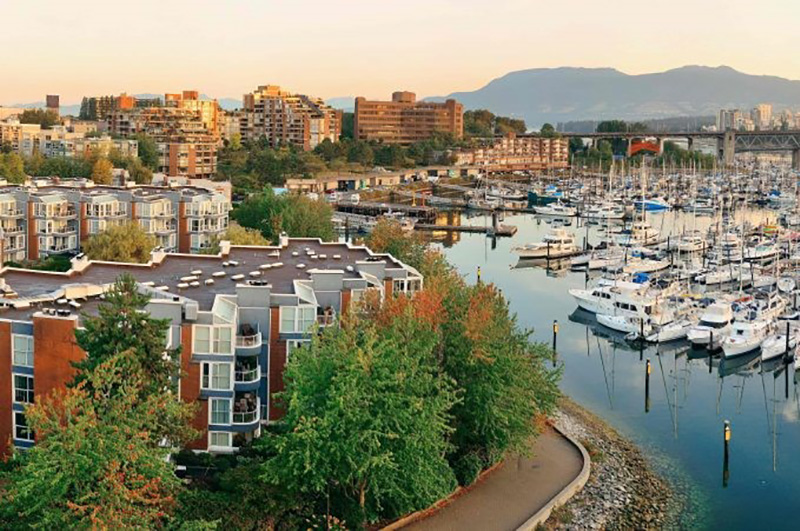

This proposal carries within it a long persistent subtext. The city has consistently taken an adversarial position with co-op owners, treating them as squatters on city land that has other more financially rewarding uses. This is particularly true at False Creek South where members of the community, with years of effort, provided at their own cost a plan to double the density of that project without highrises and without destroying the legacy lowrise verdant landscape that the entire city enjoys.

The city’s proposal seems to pay no heed of that plan and instead leaves the door open for a far more sweeping transformation of False Creek South. Of course the skyrocketing value of land in Vancouver beckons, particularly property near the waterfront. By breaking local density records, the Sen̓áḵw development at the southern base of Burrard Bridge, with its 40-storey towers, will inflate land prices even more dramatically. By some estimates, in fact, Sen̓áḵw will generate almost a billion dollars an acre in rent over its lifetime.

Presented with the prospect of cashing in on this massive land value lift, the city, with its new proposal, reserves the right to identify any land leased to a co-op in False Creek South and redevelop it. Affected co-op inhabitants are guaranteed a unit until they die, but in what kind of structure, with what community and in what neighbourhood is left unsaid.

Is this then a recipe for lives disrupted and towers rising in a part of the city that today stands as a gem of 20th-century urban design? Does this lay the groundwork for a bunch more condo highrises because the money they deliver to city coffers is too hard to resist?

It should go without saying that the park-like setting of False Creek South, entirely open to all citizens at all times, is a touchstone for what makes Vancouver so livable a city — a value that the “methodology” fails to mention even once.

Should the city intrude so heavily upon a democratic, justice-oriented model of self-governance?

The co-op model makes a virtue out of having a mix of incomes under one roof by enabling members to collectively decide how some who are wealthier should cross subsidize those who make less. The city now wants to impose itself upon such internal decisions. The city will steeply increase its lease rate to co-ops but offset that by making “grants” to subsidize some rents while asking better-off residents to pay near market rates. In so doing the city will demand co-op residents report their incomes.

The result, promises the proposal, is that co-ops will remain affordable housing because the grants will insure that no resident will pay more than 30 per cent of their income. And the proposal has some vague language saying in some cases, the new methodology “should enable some cross subsidization within the co-op.” “Should.” “Some.” Hardly reassuring.

Consider what we risk losing. Co-op projects conceal within their walls both the poor and the middle class without stigma on the former or burden to the latter. This is because for decades co-ops have had much more autonomy to make their own decisions over how to divvy up the pool of member contributions. Are key tenets of co-op living about to be undermined?

Why is the city determined to get ‘near market rates’? Isn’t this land co-op members paid for which the city nevertheless owns and therefore could lease for far less?

The terms “market rates” and “market rents” appear scores of times in the document. The city proposes to up the rents to “near market rates” for those who can afford it and use this new income to secure affordable housing in other parts of the city. This sounds fair at first blush but actually it cuts against the original motivation for co-ops, which after all were established precisely as a way to avoid market forces. Creating co-ops has been a way to set aside a portion of our housing stock free of what is now a raging out of control real estate market.

Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when these projects were initiated, the city received near market value for the land in a one-time payment, up front. The full cost of the near market land value was financed, along with the cost of construction, by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. loans. Residents paid off this mortgage financing collectively over the successive 30 years through their rents. Not too many people realize it, but co-op members paid off the entire cost of the project even if the city still owns the land. There was no subsidy beyond incentives such as loan guarantees.

Here then is the moral hazard. Residents of these co-ops, many of whom were among the original residents, chose to opt out of the regular housing market — even though many could certainly afford market options (in the low housing price environment of the ‘70s) for the socially more admirable co-op model of non-equity, mixed-income living.

Had they made different choices then, or had the city simply sold rather than leased the land, they would likely be enjoying the multimillion-dollar equity paydays of many their age and of professional peers. Instead the city is asking them to, in effect, pay for the land twice in one lifetime, while ignoring the fact that the equity value of the land they sit on has risen by more than 2,000 per cent — with pioneering residents capturing none of that land equity gain.

The city is entirely free to charge one dollar a year or anything it deems in the public’s interest. Doesn’t it seem more efficient to lock in a proven affordable housing approach — co-ops — by guaranteeing them a lease rate well below market, rather than try and profit off of co-ops and transfer that money to other affordable housing models?

Where is the guarantee that co-ops over time will remain truly mixed-income?

Surveys of Vancouver’s current co-op population show they contain large percentages of people who are low or middle income. Various times the city’s new proposal has endorsed the aim of mixed-income residents for co-ops. But nowhere in the document is it spelled out what the threshold should be, or how such a mix will be guaranteed as the co-op populations change over time. Without such language, what is to prevent co-ops from shifting toward refuges for people with upper-end incomes?

Is this or any of the other questions raised above the reason the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, with which the city has been negotiating for years over renewing the leases, rejected this proposed “methodology?”

Is there a better way?

There must be. One blueprint lies with the “homegrown solution” offered by the False Creek South community itself. But the bigger shift required lies in council deciding to put "social value" ahead of "market value." Those in the know around city hall are aware that for more than a generation there has been conflict between the planning staff and the real estate department, whose members are adamant that market values must dictate city policy and thus the maximum financial return for city assets is an inviolate first principle.

Former Vancouver chief planner Larry Beasley, and others, long since having left the city, fought a hard fight against early proposals advanced by real estate for highrise towers for the Olympic Village site. Planners won. The city was the better for their efforts.

But this battle still rages inside the walls of city hall and some of the opposing champions have left the field. Who will now fight to champion social betterment over maximum monetary gain? And in the end, what is the money for if not to secure guaranteed tenure in attractive socially and economically mixed neighbourhoods?

False Creek South is an internationally famous emblem of a time when cities tried to be better, more just, and, dare I say it, more beautiful.

Today it falls to Vancouver’s city councillors and citizens to defend that vision. They must aggressively question this “methodology” before putting at risk a neighbourhood and the co-op ideals that found a home there. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: