Last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sent 60 Armed Forces service members to Nova Scotia to assist with a record-breaking number of COVID-19 cases in the province.

That number was... 96. Cases. Not deaths, cases. Our government sent helicopters. In the last year, 67 people in Nova Scotia have sadly died from COVID-19.

In the same time frame — one year — 1,716 people in British Columbia died of suspected drug overdoses. No helicopters, no extra doctors, no Red Cross, no daily press conferences with graphs, mathematical modelling and a scrum of reporters. Trudeau said Ottawa made the decision to send the military to Nova Scotia “because the situation requires it.”

I want to tell you how this feels.

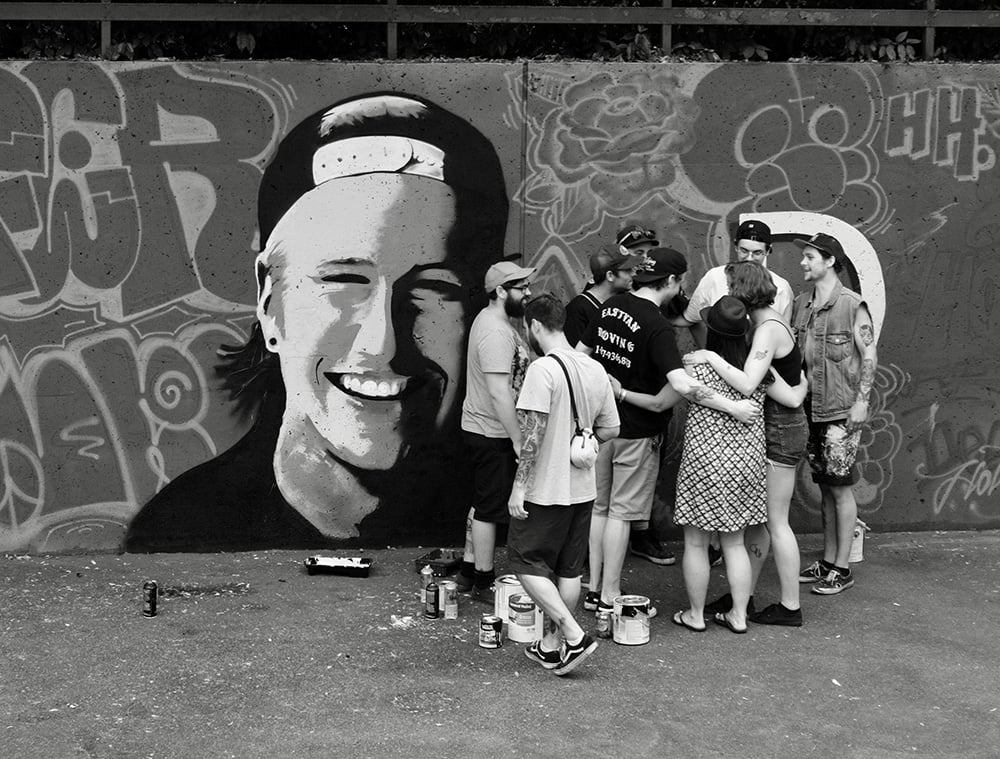

It’s been almost six years since my son Holden died of an opioid overdose; five years since an official “crisis” was declared. If my family’s loss was singular or even rare, the lack of action would be easier to understand. But since then, more than 7,000 other sons and daughters have also died. Often alone. Often without asking for help. Because the shame of asking for help is worse than the risk of dying.

In the first three months of 2021 already, 498 people have died after overdosing. Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe calls B.C.’s situation a “toxic drug emergency.” Is it still defined as an emergency when the same scenario has been replaying for five years? Or have we simply decided as a society that some lives are worth more than others? Emergency (noun): a sudden, urgent, usually unexpected occurrence or occasion requiring immediate action.

I want to tell you how this feels.

Not sudden, not unexpected. Five people a day. Every day. For five years. Five mothers who, like me, will always be less than whole. Thousands left behind who, like me, aren’t able to contribute to society the way we used to. The collateral damage is enormous. It’s estimated that for every overdose death, as many as 20 close family members and friends will sub-perform for years. If we’re cold enough to talk dollars, I don’t pay as much income tax as I used to when Holden was alive. How much do these deaths really cost?

Hours before my father died of COVID-19 in December, I held his hand. I told him he was loved and said goodbye. While an expensive machine did his breathing work, I reassured him that he was strong, but the disease was stronger. Doctors treated him, nurses attended to him, a “director of care” made sure he was comfortable and warm.

Few even knew how unwell his grandson was, how he suffered. It was a secret. Nobody directed his care. Nobody held his hand. Nobody told him that he was strong, but the disease was stronger.

When my sister was diagnosed with colon cancer, she was flown on a private jet from Trail, B.C. to Vancouver, where she stayed intermittently for months at St. Paul’s Hospital while a team of specialists cared for her. Surgeries, diagnostics, chemo, radiation, followup care for five years. What did that cost her? Nothing. Not one cent. What did it cost our medical system? I’m guessing hundreds of thousands of dollars. Was she shamed or made to believe she was weaker or less worthy because of her illness or her burdening of our system? No, she was given empathy and jello.

I want to tell you how this feels.

One night after my son died, I awoke in the dark with a deep, resonant throb in my chest. Thinking I was having a heart attack, I went to my local hospital emergency room. It turns out my heart was broken, but that’s beside the point. I was given blood tests, an EKG, a Holter monitor, an appointment with a cardiologist and a followup with my family doctor.

When a person in overdose is treated by first responders, or as is often the case, arrives in the ER, they are saved (hopefully) with naloxone, and when they come around, they are released. No protocol of care, no followup, no support. At this point they are vulnerable to overdose again, because the naloxone has in effect deactivated the opioids in their system, throwing them into withdrawal. Whatever drugs they’ve ingested are still very much present.

Addiction, like cancer or multiple sclerosis, is a disease that can relapse, meaning it comes back at times as part of its natural arc. Nobody is shamed when their cancer recurs, but when a person in recovery relapses they are usually removed from treatment and deemed a failure, leaving them more wounded and isolated. This is often when overdose occurs.

The other night during the Oscars, Travon Free, in his acceptance speech after winning Best Short Film, quoted James Baldwin: “The most despicable thing that anyone can be is indifferent to other people’s pain.”

“Please don’t be indifferent to our pain,” he said, talking about racism.

Science tells us that people who use illicit drugs do so to ease their pain, to mask their trauma, or to simply feel better.

I’ll tell you how this feels. It feels like despicable indifference.

One mother I know, whose son is fighting substance use disorder, said it took five adults; multiple phone calls, emails and favours and driving through a snowstorm during a pandemic to get her son admitted to a treatment facility in Prince George. Her voice sparked with frustration. “There’s no way he could have pulled that off on his own.” Families have remortgaged their homes to afford treatment for their children.

It feels like some people are offered more help than others.

Out hiking one day, I heard the sound of a safety whistle pierce the still green air. A deep voice calling, a name, a name, a name. Boots on the gravel path ahead. We’re looking for a man, 42, distraught, he may be injured. Or unconscious. We found his car. A search and rescue team has been activated. We’re doing a sweep. I walked the snaking trails I used to walk with my son.

A name, I called, a name, your family loves you, your family wants you. A name, I called, a name, whatever is going on I promise it will get better, I yelled to the canopy, the rushing river, the low cloud, a name, a name, they love you, they want you, they will miss you forever. They don’t care what you’ve done.

It feels like no search, no rescue, no team deployed to fan out and comb the bushes when my son, and so many others, were lost.

B.C.’s latest budget includes a pandemic fund of $3.25 billion for the current year, $900 million for COVID-19-related health measures. Fantastic. When the citizens need it, the money appears. But some citizens have needed it long before now.

There is some good news. B.C. announced the largest investment in mental health and addictions in the province’s history: $500 million over three years to expand youth mental health programs, an additional 195 treatment and recovery beds for substance users, and expanded programs that respond to the overdose crisis. That includes $330 million for treatment and recovery services for substance users, $152 million of that for opioid treatment.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said she is “very, very pleased” the province has allocated these funds and hopes the federal government will respond quickly, “as it has shown it can with the parallel COVID-19 health crisis.”

As it has shown it can.

The opioid crisis, or parallel pandemic as Henry calls it, was actually here first — Holden riding the crest of the first wave in 2015 — and though it is arguably more deadly, it is overshadowed by the cleaner, more presentable one. Holden was just one kid, one stat, one privileged white young man who had all the advantages, except his pain was just as real to him as anyone’s pain is to them. His confusion, his fear, his illness, just as valid.

It feels like a distinction is being made about which lives are worth saving, based on dollars in government funding, and which lives are not.

Addiction is complicated. It’s slippery. There are many qualified opinions about how to approach this long-term devastation, and none of them are easy.

All I’m asking for is equity. All I’m asking for is that my son’s life and the lives of other smart, sensitive people who use substances be considered with the same weight as those we are currently protecting from COVID-19. Even when their illness mutates and proves unco-operative.

That would feel a lot better. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: