On Oct. 4, 1938, Edward Rogers and Luigi Mancuso decided to grab a glass of beer on their way home after work.

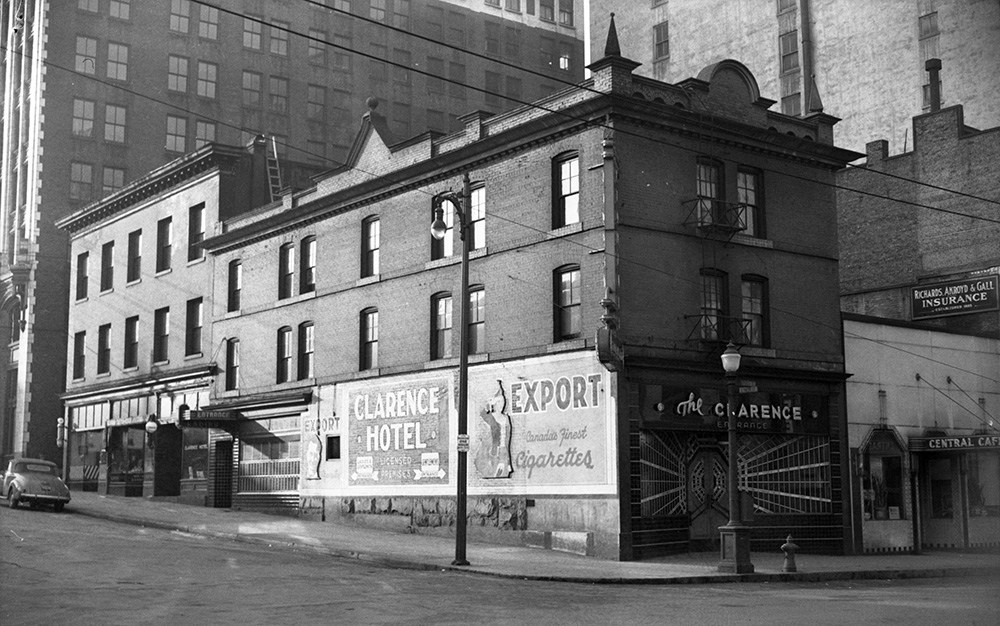

The business partners locked their Pender Shoe Renew shop at 520 W. Pender in downtown Vancouver, next door to the Waldorf Café (later the White Rose Café). They walked west past a shoeshine stand, a tobacco shop, an auctioneer’s and the Toronto General Trust building before crossing Seymour Street to enter the Clarence Hotel.

The lounge was under new management. A newspaper advertisement the previous month proclaimed the hotel a Vancouver landmark. “We have spared no expense nor neglected a single detail that will add to the comfort and pleasure of our patrons,” the ad stated. “Come and meet smiling Rose and Bill Low at the new place.”

The renovated refreshment parlour, as it was billed, featured small round tables with carefully placed quartets of upholstered wingback armchairs. The long, rectangular room had a small bar in the middle. The well-appointed lounge included electric light sconces above wainscotting. Waiters in white jackets served the customers.

As it turned out, the Clarence was not prepared to pleasure all patrons.

A waiter refused to serve the men beer.

Rogers, 68, who had been born in Kentucky to a father of Indigenous ancestry and a mother of mixed race, was Black.

“I am a businessman here, a taxpayer, a voter, and a British subject,” Rogers told the waiter.

The waiter insisted he had instructions from management not to serve Black customers.

Negotiating the casual cruelties of discrimination in Vancouver, as in other cities, was a daily frustration faced by non-white residents. Some white-owned bars, hotels, restaurants, night clubs and barber shops imposed racist rules based on skin colour and ethnic origin in Canada’s own version of Jim Crow.

Though he might have been a lowly bootblack for some of his working life, Rogers was a war veteran. He had met the mayor. Back in the day, he had squired American jazz musicians around Vancouver, showing off his city. He had undoubtedly faced his share of discrimination and did not care to endure such humiliation again. He decided to sue for damages.

Rogers was an ordinary man who sought to correct an injustice with which he was confronted while trying to go about his daily life.

From that day until today, he has gone mostly unnoticed and certainly unprofiled, a figure all but forgotten save for lending his name to a civil liberties case still referenced on occasion in court — Rogers v. Clarence Hotel Co. Ltd.

Who was Rogers, and why did he decide, at last, to confront a prejudice which had been a defining feature of his life? Could he find satisfaction in the law?

The story of the principals — the aggrieved plaintiff and the publican who refused to serve him — offers a snapshot of daily life in Vancouver from an era when overt discrimination was common and legal. The city’s three daily newspapers provided bare coverage of the case, which even in legal circles was overshadowed by a similar suit launched in Montreal.

In the subsequent decades, Canada’s ugly legacy of Jim Crowism has almost entirely disappeared from public knowledge.

The path to Vancouver

Edward Tisdale Rogers was born on April 28, 1870, in Louisville, a stronghold for Union forces in the border state of Kentucky in the Civil War that ended just five years earlier. Little is known about his childhood and early life. It is possible his mother had endured involuntary servitude as a slave.

Due to widespread racism and the indifference of officials, it is difficult to track with certainty a paper trail for some African Americans in the years after the Civil War.

The only physical description of Rogers in the public record comes from a border crossing in which his height is listed as 5-9.

Records show a man with the same name and a similar biographical background moved to Indianapolis, where he worked as a porter before enlisting in the all-Black 48th U.S. Volunteer Infantry during the Spanish-American War.

On June 1, 1900, during the U.S. census, he was serving as a sergeant in the Philippines. After returning home, he worked as a waiter and with a partner opened a restaurant named Lee & Rogers just two blocks from the state capitol.

Rogers married Nelo Taylor, a white woman, in Chicago in 1913. The couple arrived in Vancouver five years later. They settled into a wooden house at 940 Main St., sandwiched between the Canadian Café and the State of Maine Junk Co.

The house rented for $40 a month and was near businesses catering to the city’s thriving Black community. Rogers worked for Canadian Pacific Railways, possibly as a waiter or porter.

The following year, while part of a delegation that met with railway management in Montreal, he wrote the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper with national distribution. “[My] mission was a success, as 92 per cent of the dining car division of the CPR secured a fine raise in salary and insurance that brings $200 in case of death,” he wrote.

He also informed readers about the exciting jazz scene in Vancouver, which reminded him of the vibrant life on State Street in southside Chicago.

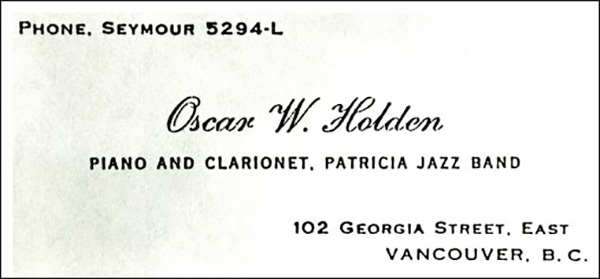

“Well, Will Bowman has opened a cabaret here and is doing fine,” he wrote. “He has an 8-piece jazz band with Oscar Holden, Leo Bailey, Jelly Roll, Ada Bricktop Smith and others, with Mrs. E.T. Rogers cashier. Tom Clark has a neat little café, Reg Dotson still has the Lincoln club, Jean Burt and Perkins have opened a nite club and café, so [Granville] street looks like some parts of the Stroll.”

Nelo had also found a job in Vancouver, working for Bowman at the Patricia, a hotel boasting a 390-seat ballroom and the largest dance floor in the city. The roster of Chicago musicians drew little interest from the white reporters with the daily newspapers, though Ferdinand (Jelly Roll) Morton and Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith, dubbed Bricktop for her red hair, became two of the most famous names in jazz.

Bricktop was said to have taught the Charleston to the Prince of Wales, had a song written for her by Cole Porter (“Miss Otis Regrets”) and about her by Django Reinhardt (“Bricktop”), while her Parisian nightspot Chez Bricktop appeared in works by such patrons as Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

It is not known how long Nelo Rogers worked as a cashier at the Patricia cabaret. Her husband had an entrepreneurial bent with mixed results. He ran a confectionary shop, and in 1923 got a city licence to operate the Pullman Club, a combined pool room and two-chair barber shop at 804 Main St. It lasted less than two years.

Subsequent events at that address give a hint as to the nature of life in the neighbourhood. Police raided the address in 1927 and charged four men, including one who gave his name as George Vodka, with running a betting house.

Two years later, the store housed a Japanese grocery. A clerk was victim of a venerable scam when she gave change for a 40-cent purchase made with a worthless $20 Confederate banknote. That same year, Nelo reported the theft of three diamond rings and other jewelry from her home.

Shortly after the burglary, the couple moved to a new home at 217 E. King Edward St., just east of Main Street, where they rented a room to a pensioner.

After closing his club, Edward Rogers worked as a taxi driver. He then ran the cigar stand at the St. Regis Hotel before taking over a shoeshine stand at the busy bus and taxi depot around the corner on Dunsmuir Street, where he would also work as a janitor.

Rogers operated a storefront shoeshine stand on Robson Street before being hired as a shiner and dyer at Pierre Paris, a well-known boot and shoemaker specializing in orthopedics. The company also employed Mancuso, and the two men opened a business not long before the fateful day they decided to quench their thirst at the Clarence.

Rogers was politically aware. When newly-elected mayor Gerry McGeer arrived for his first day of work at City Hall, Rogers was on hand to present him a rusty horseshoe decorated with a bow of green ribbon.

Taking the battle to the courts

If Rogers was to launch a legal fight against Jim Crow in the city, he was going to need some help.

He hired Adam Smith Johnston, known for an erect posture, his cigar smoking, his old-school style — and as the best-dressed lawyer in the city. He was a go-to attorney in high-profile cases.

Some 420 days passed from the day the men were refused a beer until their cases appeared on the trial list for the BC Supreme Court. Then the matter was adjourned to await a decision in a similar case under consideration by the Supreme Court of Canada.

In 1936, Fred Christie, a Jamaican-born chauffeur, entered the York Tavern inside hockey’s famous Montreal Forum with two friends, one a white French-Canadian and the other Black like himself. Christie, who had been served in the tavern before without incident, put two quarters on the table and ordered three glasses of beer. The waiter and the bartender refused to serve him because of his race.

Christie might have been denied service because the event in the Forum that night was the Olympic boxing trials, which included a Black hopeful, and boxing crowds sometimes reacted violently to outcomes. (Though it was white crowds that violently opposed celebrations of Black victories.)

Christie sued for breach of contract and was awarded $25 in damages. The tavern won the appeal and then Christie brought the case to the Supreme Court of Canada, where the tavern’s right to refuse service for any reason, including racial discrimination, was upheld in a 4-1 decision. The justices found “freedom of commerce” prevailed over whatever claims to equal treatment the chauffeur might have expected as a citizen. Christie v. the York Corporation gave the law’s imprimatur to racial discrimination.

It was in the wake of that decision that the Clarence Hotel incident was heard in BC Supreme Court.

On Feb. 21, 1940, Rogers told Justice D.A. McDonald that the refusal to serve him was without excuse and against the law. He claimed unspecified damages for humiliation and inconvenience.

The defendants, represented by prominent litigator George Lovat (Pat) Fraser, insisted they could serve whom they pleased.

When Rogers and Mancuso entered the Clarence Hotel on that day in 1938, they would have seen the manager’s name painted in large letters on the wall of the Seymour side of the building: “R.E. Low, Proprietor.” The notice was flanked by painted advertisements for British Consols cigarettes, including one featuring the tobacco company’s famous Scottish lassie in Highland garb offering a military salute.

Rose Elizabeth Low and her husband Bill had been managing hotels since arriving in Vancouver from their native England in 1905. They handled the Burrard, the Martinique and the Empire, where she was known for having nursed merchant seamen suffering from the Spanish flu.

After the Clarence, she managed the Merritt Gordon, soon after renamed the Marble Arch, purchasing an advertisement in the newspaper describing her as “well-known all over the world as the kind and jolly proprietress of many years standing in this community.”

Rose was the only woman on the executive of the hotel association and the first woman in the city to hold a beer parlour licence. Her long activism in the Liberal party won her frequent favourable mentions in the Vancouver Sun, at the time a pro-Liberal newspaper. When the Sun sponsored a walking marathon in 1939, she donated a silver entrée dish as a prize for the oldest married woman to finish the course. The Lows also sponsored bowling teams.

In his judgment, Justice McDonald ruled the recent Supreme Court of Canada judgment against the Montreal chauffeur was not applicable in this case. He cited the dissent by Justice Henry Hague Davis, stating the issue was not one of freedom of commerce, since licensees held a government-imposed monopoly on the sale of beer by the glass.

“It is a matter of very great importance,” McDonald said. “It is particularly important in a city like Vancouver, the terminus of two continental railways and the home of many coloured men. Those of us who, in the course of our duties, have to travel on the trains, have brought to us from day to day the honesty, intelligence and kindness of those men and I must consider their rights and the rights of their coloured brethren with the very greatest care.”

He awarded $25 in damages in a ruling that abolished what at the time was described as a “colour line” in drinking places.

Rose Low appealed.

At the Court of Appeal, Rogers’ lawyer argued that reversing the principles of equality found in McDonald’s ruling would be the “thin edge of Hitlerism in Canada.” If a beer parlour could deny drink based on colour, then what would stop a proprietor from refusing to serve Catholics? How long before Canada descended into the discrimination that had become a feature of European countries embroiled in war?

Low’s lawyer argued a proprietor had unfettered right to deny service.

The Court of Appeal agreed, setting aside the damages. Once again, the law enforced racist practices.

In a dissent, one judge insisted Rogers had been wronged, as he had faced discrimination solely because of race.

“All British subjects have the same rights and privileges under the common law — it makes no difference whether white or coloured; or of what class, race or religion,” Justice Cornelius Hawkins O’Halloran wrote.

Despite being described in contemporary newspaper accounts as the first of its kind to come before the courts of British Columbia, Rogers v. Clarence Hotel was at least the second such case in the province.

In 1914, James Barnswell purchased a 10-cent ticket for a show at the Empress Theatre on Government Street in Victoria. When he tried to enter, the doorman put hands on him to bar his entrance. The manager offered to refund the ticket, but Barnswell held onto it as evidence. Two weeks later, he was in court seeking compensation.

The theatre had a “rule of the house that coloured people should not be admitted,” court was told.

The 35-year-old Barnswell, who had been born in Victoria and worked as a labourer for the David Spencer department store, sought damages and the right to admission to local theatres without discrimination.

Equal access had long been a goal for the city’s Black community, which was established in 1858 on the invitation of Gov. James Douglas. Just three years after the first settlers arrived from San Francisco, other white Americans attacked Black patrons in formerly whites-only theatre seating by throwing a bag of flour on them.

The trial judge awarded Barnswell $50 in damages for humiliation, a decision upheld 2-1 by the BC Court of Appeal. The case, Barnswell v. National Amusement Co., has been overlooked as a precedent, perhaps because, as noted by legal scholar Constance Backhouse, judges were reluctant to explicitly discuss race and a summary of the appeal neglected to do so.

Rogers’ reaction to losing the appeal is unknown. Reporters didn’t ask him. His business partner Mancuso, a Calabrian immigrant from Spezzano della Sila who arrived in Halifax shortly after Christmas in 1928, had also sued but the judgment put an end to his case as well. He continued to operate a shoe repair business until his death in 1969.

Rose Low died suddenly in 1947 of a coronary occlusion a year after her husband’s death from colon cancer. “The poor and needy were represented at her funeral as well as many a prominent citizen,” the Sun reported, “all of whom remembered the kindliness of a woman whose generosity was a byword.” In her will, she left $4,000 to a home for the aged.

It is not known if Rogers and Low ever met again outside the courtroom. In an odd twist, they both were victims of a small-time fraudster in 1943. Leonard Preece, a white, English-born cook, presented a bad cheque for $10 to Rogers at the shoe repair business and forged a cheque for $23 at the Marble Arch beer parlour. He was sentenced to three months hard labour on the forgery with a month concurrent for the bad cheque.

Rogers continued working until age 84. Soon after, he was committed to Valleyview Hospital in what is now Coquitlam suffering from dementia. He died there in the midafternoon of Aug. 28, 1961, aged 91. He was cremated and buried at Mountain View Cemetery a little over a kilometre from the family home.

His wife died at 85 of a bleeding ulcer the following year. The official administrator handled the estate, selling her effects. According to city records, she was buried with her husband, though the grave marker includes only his name. There was no one left to order a new marker.

Neither lived long enough to enjoy the benefits of effective anti-discrimination legislation.

The Social Credit government of W.A.C. Bennett began instituting anti-discrimination laws in 1956. It was not until the NDP government of Dave Barrett passed the Human Rights Code of B.C. in 1973 that such blatant discrimination as refusing to serve a glass of beer on account of race was outlawed.

The Clarence refreshment parlour is now occupied by Malone’s Social Lounge and Taphouse. It is a place where toasts should ring out in memory of Edward Rogers, a man who simply wanted a glass of beer after an honest day’s work. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: