Portland has implemented a new zoning law with features that just might solve the city’s affordability crisis. Vancouver should follow its lead.

Earlier this month Portland city council voted 3-1 in favour of its “residential infill proposal” after four years of debate.

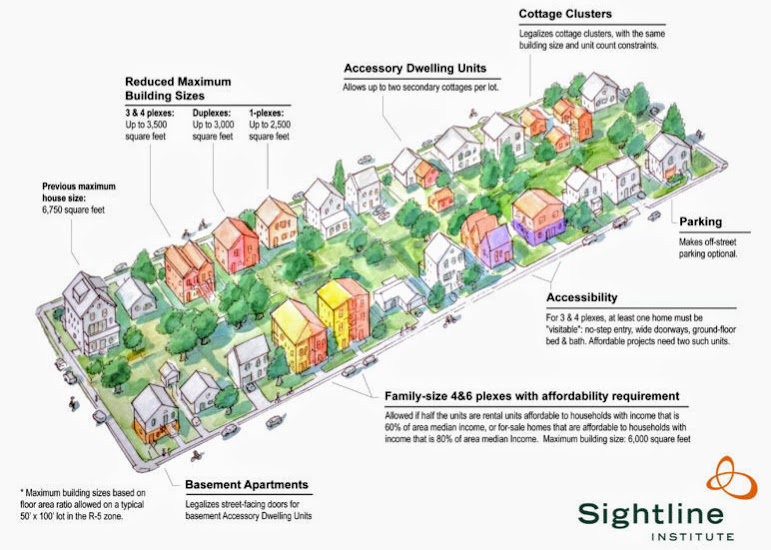

The new zoning bylaw brings a raft of changes, including limiting new single-family homes to 2,500 square feet (down from 6,500 square feet), encouraging multiple units on most lots and slashing requirements for off-street parking.

But the biggest boost to affordability will come from a provision allowing up to six dwelling units on all residentially zoned lots in the city — including the more than 50 per cent of the city zoned “single family.” (That’s in quotes because Portland already allows a second dwelling — or “accessory units” in areas with single-family zoning.)

To be allowed to build the maximum six units, developers will have to ensure three of the units are made affordable to average wage earners.

The measures offer a pathway to achieving true affordability in every Portland neighbourhood at no cost to the taxpayer. The city says they will “provide opportunities for a wider variety of housing options and can reduce the cost of a single unit by roughly half the cost of a single new house.”

This approach could certainly work in Vancouver and surrounding communities. Portland has, perhaps for the first time in North America, committed to “density bonusing” in return for more affordable housing in single-family zones.

Why does this matter? Because simply adding allowable density without requiring affordability just leads to land price inflation. In the end you just get bigger buildings with no decrease in the per-square-foot price of the units. The only beneficiaries are the land speculators, and they are rich enough.

Builders that agree to make half of new units in formerly single-family zoned neighbourhoods permanently affordable (typically by transferring ownership of strata-titled units to non-profit housing corporations or by being developed and owned by non-profits) will get a substantial density bonus. The increased overall profits will be an incentive to provide the affordable units.

And Portland has set a strict definition of affordability. Units in six-unit buildings must be affordable for families with 60 per cent or less of the city’s median income.

It took four years worth of meetings and 38,000 individual mailings to mitigate fears and incorporate important neighbourhood residents’ views into the final plan.

It requires new buildings to respect a neighbourhood’s character (often a difficult concern to satisfy, and even harder to define) by not overshadowing neighbours.

Importantly, the city eliminated on-site parking requirements for affordable units, freeing up lot space for gardens and structures. This is always a contentious issue and not everyone in the city agreed. But in the end councillors understood that affordability objectives could not be met if much of a redeveloped site was used up for car storage.

Also critical, the city will require the preservation of character homes as part of any plans.

The changes are about much more than affordability, important as that is.

Coun. Chloe Eudaly, a tenants’ rights activist, said social and racial justice issues also drove the initiative.

“For over 100 years, exclusionary zoning laws have kept certain types of housing, and therefore certain classes and races of people, out of single-family neighbourhoods,” she said. “Simple upzoning will not remedy past harms or guarantee more affordable housing and diverse neighbourhoods. That is why I've worked so hard to ensure that we included incentives for affordable housing, commit to developing and implementing anti-displacement measures, and encourage the preservation of existing housing,”

Sean McEwen, a well-known Vancouver housing advocate and architect of the award winning Mole Hill housing rehabilitation in the city’s West End supports the changes.

“Portland’s new zoning to gently densify single-family zoning areas gets it exactly right,” he says. “A low-rise scale is kept in existing neighbourhoods, with a wide range of housing options that promote housing affordability and compatible housing forms. No land assembly is required to densify, and no off-street parking is needed. And the approvals process is significantly simplified and made far less onerous.”

“This kind of zoning will allow existing homeowners to contemplate adding density on their properties to better accommodate aging in place, and providing separate housing units for grown-up children who can’t afford to buy back into the neighbourhoods they grew up in."

There are legitimate criticisms of the changes. The requirement for affordability only kicks in when six units are planned. If developers choose, they can build four units, and they can be sold or rented at market rates. There is a fear most projects may just add expensive units, displacing families with no social benefits realized.

And the bylaw does not specify the size of the affordable units, so there is an incentive to make them very small and unsuitable for families.

Vancouver would be wise to adapt the Portland approach to reflect our realities. The gap between income and land prices in Vancouver is almost double what it is in Portland. This makes it more crucial to require social benefits more universally. But the demand for real estate here also makes it possible to require more social benefits from redevelopment.

But the Portland model could be adapted to our circumstances and deliver more affordable housing without taxpayer subsidies or inflating land prices.

It took Portland four years to get its bylaw passed. Given Vancouver’s affordability crisis, officials should incorporate similar proposals into the city’s ongoing city plan efforts and move more quickly.

The benefits could be great, providing a no-cost solution to the city’s housing crisis in time to stem the exodus of those currently priced out of town. ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: