The coronavirus has suddenly made roads less used by cars, and roomy sidewalks highly prized. Imagine if you could walk out your door right now and stroll down a streetscape like the one in the picture at the top of this piece?

Shown is a modification of a concept by Vancouver’s own city planning and engineering departments. It’s from their Rain City Strategy, crafted to propose changes to the appearance, function and ecological performance of many of the city’s streets.

Well, wouldn’t this be nice now? A capacious walkway down the middle of what used to be pavement prowled by cars, bordered by grassy swales, plenty of room for kids on bikes, dog walkers, ambling seniors, everyone cruising along at their own pace and a safe social distance without feeling like they have to dodge each other.

Add this picture to a thick file accumulating around the world in response to COVID-19. In many places, cities already are closing off streets to traffic, to release former car space to pedestrians. New York City is proposing to close off 100 miles of streets, Milan, Italy, 28 miles, and Oakland, California, 74 miles. Canadian cities have been slower to respond.

Vancouver announced plans to close streets in mid-April but as of yet has closed only the Stanley Park Drive and Beach Avenue to traffic. Coun. Lisa Dominato would like to see more streets closed, introducing a motion in council this week to do so. Council is scheduled to discuss the idea tonight.

If Vancouver does proceed, there could be other major benefits. The Rain City Strategy, tabled far before the pandemic changed the world, was designed to solve an expensive problem and create a network of “green streets” at the same time.

What was that problem? “Combined sewer overflows” that are still polluting our beaches and rivers. To solve the CSO problem using conventional means would cost over $7 billion to fix (or in more understandable terms roughly $11,000 for every woman, man and child in the city).

The Rain City Strategy grew from a desire to solve the problem more intelligently and cheaply. Rather than completely reengineer the city’s sanitary sewer and storm water pipes, the plan suggested you could leave those pipes in place if you could figure out a way to hold, absorb, and naturalize storm water flows on site, keeping clean rain water separate from toxic sanitary waste by holding it on the surface — to either be absorbed in the soil or to flow to grass “bio swales.”

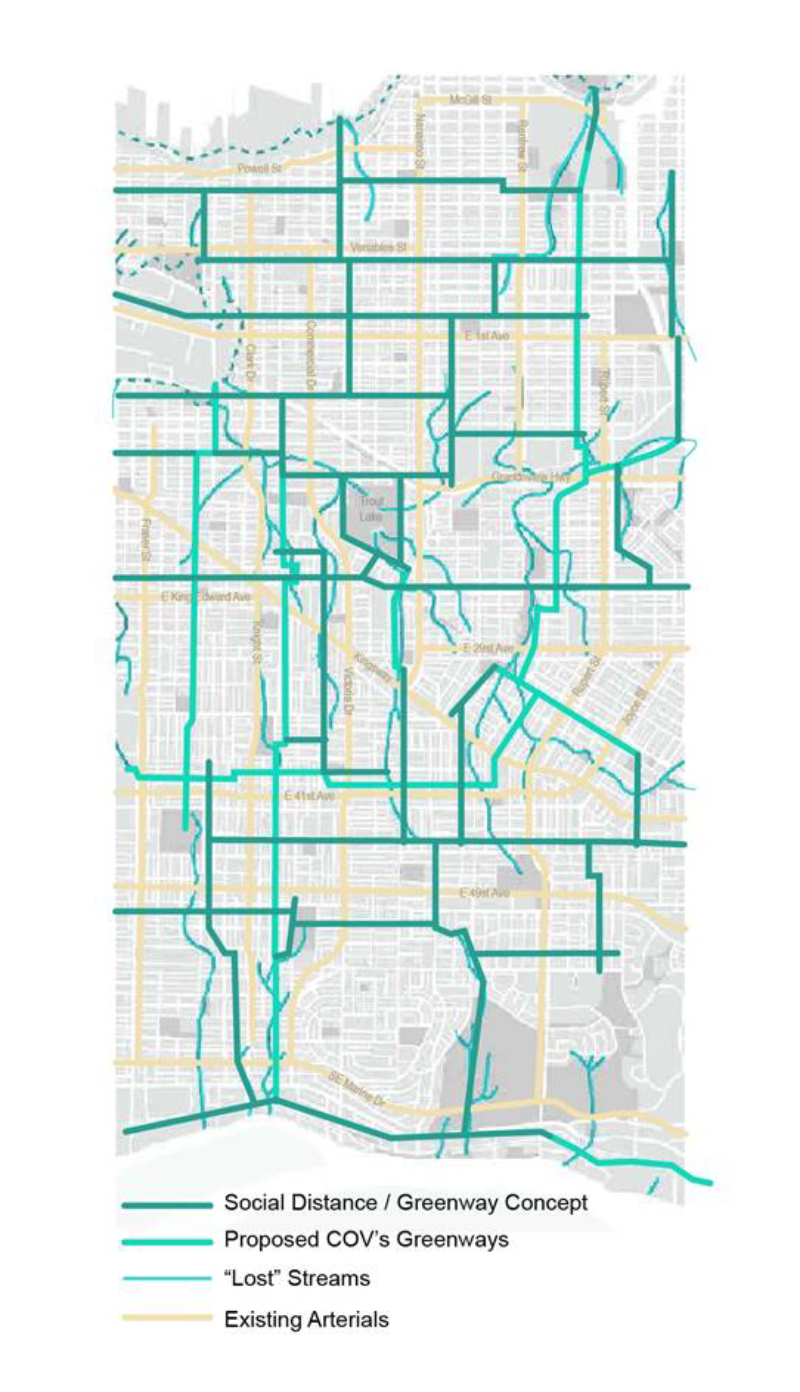

A principle strategy proposed in this plan was to introduce a city-wide "blue-green" street network. The plan identified streets aligned with locations where there were once streams and thus are still aligned with low points were storm water flows still course through buried pipes. The principle here is that it would be cheaper, and better, to re-naturalize streets lying over these “lost streams” than to dig out the large combined mains to replace them with a double pipe system. Blue-green streets are only defined in concept and their locations are left unspecific in the plan. But the logic is compelling.

It is worth reviving interest in the Rain City Strategy and to expand its scope to include the new imperative of maintaining social distance, while allowing citizens to move around the city enjoyably. As just one example of how this might look, the map shown above expands on the Rain City Strategy by increasing the number of blue-green streets beyond what that plan proposed; Such that every neighbourhood includes a blue green street and the system provides a universal walk-bike network. While the map may seem a dramatic shift, it suggests improving less than 10 per cent of city streets.

What improvements would be made to those streets? Many variants beyond the picture at the top of this article are imaginable. Streets could be completely closed except for local and emergency vehicles. Or one-way shared streets based on Dutch examples could be used. Or simply widening sidewalks and replacing conventional storm drains with grass infiltration swales.

Whatever is done should depend on neighbourhood input. Communities in Oakland, for example, took their first immediate steps at virtually no cost by posting signs that say, "Local access only. Speed limit 20 mi/hr.” One significant value here is that no costly street reconstruction is required (though the environmental benefits are slight).

In the perspective example shown the existing sidewalks and much of the existing roadway surface is retained. The construction involves only the removal of curbs and gutter and the surgical removal of a strip of roadway paving on each side — more of a reduction than a reconstruction. The cost for sewer separation has been estimated at over $100,000 per block. The design shown above could be built for less than that and, as mentioned above, would not need to be implemented on every street.

As we reconsider the post-COVID-19 city the time seems right to start to think in systems terms. This means searching for “both and” solutions to pressing problems — always solving more than one problem at a time, and ideally saving taxpayer dollars.

If we don’t think deeply now, at the moment when so much is changing, we might miss a golden opportunity to create more than just social distance, but a real “sociable distance” in a truly green city. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: