At another time, in what has now become another world, I followed my father, Frank, in the final stretch of his near 15-year marathon with dementia.

The last leg was incredibly difficult to watch, and I imagine in his deep recesses, extraordinarily uncomfortable and dehumanizing for my dad.

In the months leading to his passing on March 25, 2019, my pa’s existence was mainly restricted to a high-back reclining wheelchair.

Out of loneliness or because of his condition or both, my dad would regularly shout — usually “hello” — in a loud voice that one could hear down the hallway at Saint-Vincent, the only hospital in Ottawa that also provides continuing care. The outbursts assured him a private room, to minimize disruptions to other patients, and a care worker provided by the hospital, who stayed with my father overnight to facilitate a good night’s sleep in the comfort of company.

For a highly sociable man, renowned for his storytelling and appreciated for his easy conversational style with anyone he met, human contact — and connections to his life — were critically important.

On visits with my dad, I’d bring my cocker spaniel Claire, cookies he would quickly gobble up, and Diet Pepsi, which he occasionally sipped with a shot of white rum.

I remember one night together, vividly. We looked at photo albums, as my dad pointed out people he remembered from our hometown, Winnipeg. Other memories from my father’s life filled his room.

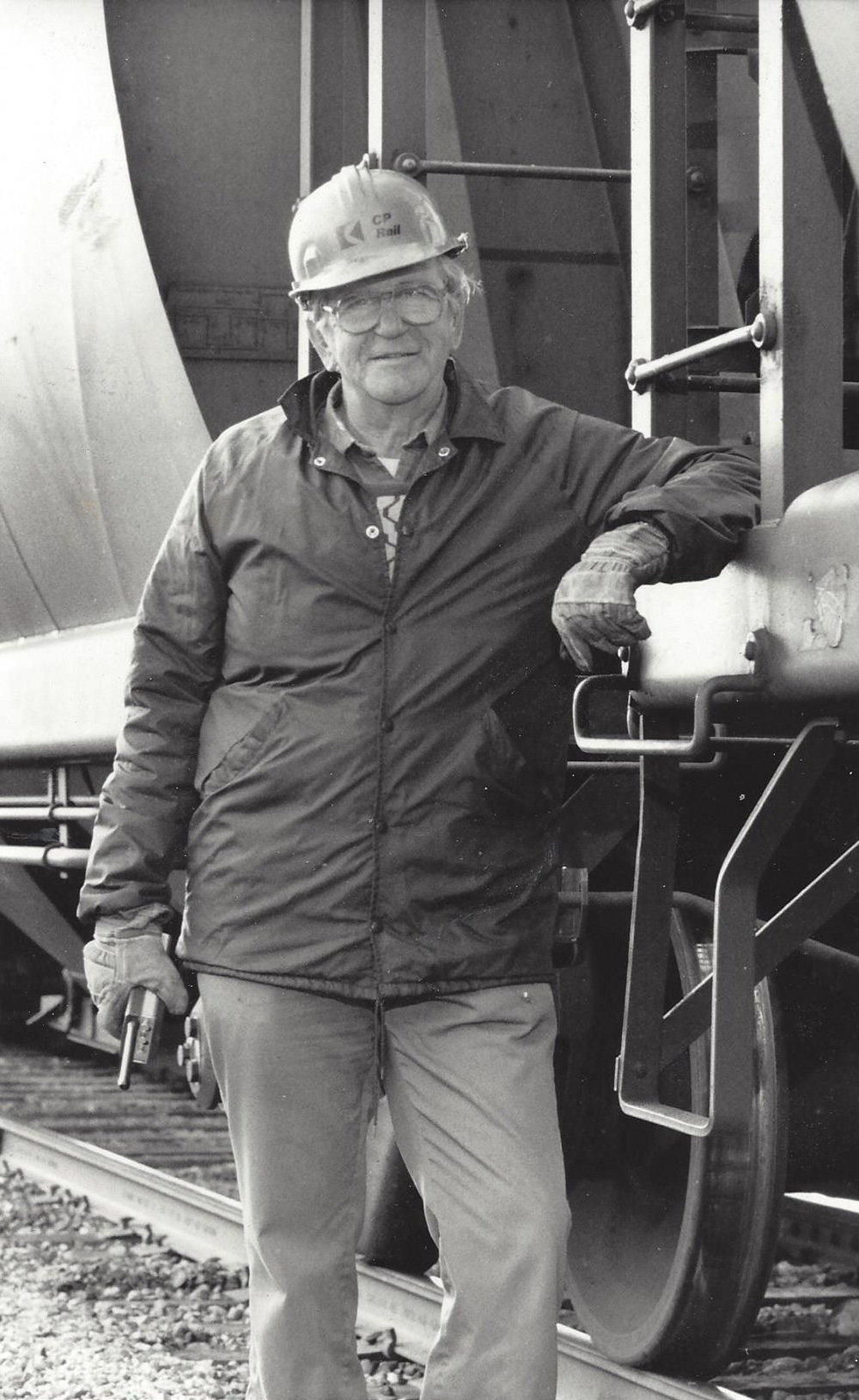

On one wall hung a large black-and-white photograph taken of him at the CPR yards in Winnipeg’s North End to mark his retirement following a 45-year career with the railway. His 1999 induction into the Manitoba Baseball Hall of Fame, as a member of the Canadian Ukrainian Athletic Club Blues, the four-time Greater Winnipeg Senior Baseball League team champions, sat on a side table, encased in glass.

That visit lasted only a few hours. I want to think it reminded my pa that he was not alone. In me, it reinforced the preciousness of our time together.

These memories come to mind as the toll of COVID-19 mounts scandalously in Canada’s senior care facilities, and risks of infection prevent families from being with their elder loved ones just when providing such comfort is so important.

For a moment in Ottawa, even just appearing at a senior’s window to wave hello was outlawed — until a public outcry reversed the decision.

Determination and desperation drove one Ontario woman to stay in touch with her mother by putting a camera in her room despite receiving pushback from the long-term care home where her mom resides.

In Canada, residents of long-term care facilities have become, by far, the pandemic’s greatest victims, accounting for 81 per cent of COVID deaths as of May 8, according to information provided to The Tyee from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Soldiers have been sent to help short-staffed facilities in the hardest-hit provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

As of May 10, 1,235 resident deaths have been reported in long-term care homes in Ontario.

As the Globe and Mail reported last Thursday, 2,114 of the 2,631 Quebecers who died of COVID-19 lived in an elder-care facility.

Last Tuesday, Amanda Vyce, a senior researcher with the Canadian Union of Public Employees, which represents care aides, testified in a virtual meeting of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health.

The “deadly crisis” occurring in long-term care was not created by COVID-19 and the “systemic issues that facilitated this heartbreaking situation existed long before this moment,” she said.

“What the pandemic is doing is shining a spotlight on those problems and making them worse. The situation is totally unacceptable.”

She recommended that the federal government reach an agreement with the provinces and territories to bring long-term care under the Canada Health Act as a universal and accessible health-care service — and one that should receive funding from the Canada Health Transfer.

Vyce also called for a national standard of 4.1 hours of daily care for every resident (not the six minutes allotted to get a senior up and ready for the day in Ontario).

And, there should no longer be privately-owned, profit-motivated nursing homes, she said.

Last month, the Ontario Superior Court sided with the Ontario Nurses’ Association in ordering four for-profit long-term care homes to comply with provincial infection control, and health and safety standards during the COVID-19 crisis.

A $120-million class-action lawsuit has also been launched in Ontario against Revera Inc. and, as of Tuesday, Sienna Senior Living Inc., which own and run nursing and retirement homes in the province, alleging negligence and deficiencies in care during the pandemic.

Ontario’s minister of long-term care Merrilee Fullerton, a family physician, acknowledged that the nursing-home sector “has been neglected for many years.” The system is “broken,” admitted Premier Doug Ford, whose 95-year-old mother-in-law — a resident of a Toronto nursing home — tested positive for COVID-19.

The federal government is providing wage top-ups for “low-income essential” staff employed at long-term care facilities as part of the federal government’s $3-billion emergency contribution announced on Thursday. And Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, surveying the nightmare landscape of long-term senior care exposed by the pandemic, has said: “Going forward in the weeks and months to come, we will all have to ask tough questions about how it came to this.”

Tough questions must lead to serious reform.

But whatever reckoning comes for this moment of national shame, the process of moving an aging loved one into a nursing home — already fraught with emotion and frustration — will only become more anxiety-provoking.

Even after his diagnosis of dementia, my father lived in a retirement home where he was quite independent — doing his own laundry, managing his own medication and holding court in the main lobby with his flock of friends. But the reality that his illness would worsen loomed. And so, having power of attorney, I helped compile a list of long-care nursing homes to apply to, so that option would be there when needed.

It seemed the compassionate as well as practical next step, given that nursing facilities are mandated to provide additional nursing and personal care that my father’s retirement home could not offer.

In creating the list, I did my due diligence, visiting several long-term care homes before finalizing a list of five.

The best of the bunch, nearest to me as it turned out, was Fairview Manor in Almonte, just outside of Ottawa, where my dad had spent a brief stint in respite to test-drive the facility. It was the best, as I say, but still nerve-wracking, because it included people whose dementia, compared to my father’s, was more severe, causing them to shout and wander. After one woman repeatedly entered my father’s room — perhaps thinking it was hers, as is common on memory-loss units in homes — I pulled my pa out of the place after a couple of days.

Almonte was where I also saw a facility that I ruled out as a home for my dad. I spent only a few minutes at the entrance of Country Haven before quickly retreating.

The lobby was crammed with frail-looking residents in wheelchairs and using walkers. My father, I felt, would have better adjusted to a long-term care centre with a more active crowd in a larger space.

As of last Wednesday, the 82-bed home had reported its 26th COVID-19 death.

Twice nursing homes on my list offered my father a bed. Twice he turned them down, and I am thankful now that we never did make the move. But at the time, I felt we were caught in a closing trap.

When a long-term care room becomes available, the would-be resident or his or her power of attorney representative has 24 hours to consent to admission. If the offer is declined, the person is taken off the waiting list and has to wait three months before reapplying for up to five long-term care homes and wait for a placement in a process that could take years, as it did in my father’s case. Saying no now, even if you have misgivings, could leave your loved one without needed care if things take a sudden turn for the worse.

My father’s slow decline lasted nearly 15 years, beginning when, at age 79, he was diagnosed with a mild form of vascular dementia following a nasty fall on Father’s Day 2004 in Winnipeg. When he died at Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital last year, it was a release from crippling Lewy body dementia, which included disturbing hallucinations and eventually the inability to swallow.

Along the way, as I sought out expert advice and support, there were some allies with answers. They included the Winnipeg neurologist who agreed to put my dad on Aricept, the drug to treat Alzheimer’s disease that my father did not have but which did end up helping prevent a deterioration of his mental function. And the general manager of the Ottawa retirement home who spent weeks working with me to find a suitable arrangement for my dad before he moved in.

But there also were too many hard-fought battles. The first was my trying to help my mother, Ollie, manage proper care for my father in Winnipeg. Then, when she suddenly died in 2012, I needed to pick up the baton. My father moved to my city of Ottawa the day after her Thanksgiving long-weekend funeral, and creating for him the best possible life became my focus as his primary caregiver.

At first that meant handling all of my dad’s care needs — from shower assistance to meal preparation — 24-7 until he qualified for Ontario health insurance coverage and could obtain home care. But that assistance never exceeded three hours a day. Other days, for an hour or so, the personal support worker would help my father with showering and dressing, going for a walk and hanging out with him at breakfast, which I always made.

As tiring and at times stressful that caregiving could be, it was mild compared to the bullying, combativeness, indifference and ineptitude I had to contend with in advocating for my father and his needs.

When my dad experienced severe delirium, not long after his arrival in Ottawa, he was admitted to hospital — thanks to the emergency-room triage nurse who recognized caregiver-burnout in me. But his weeks at the Queensway Carleton were hardly reassuring for me.

My repeated requests for a psychogeriatric workup, as per instructions I received from my father’s Winnipeg family doctor who knew my dad’s history, were denied and substituted by a general psychiatric evaluation. When I raised issues of concern or asked questions, the responses often led to heated discussions with doctors and nurses, which were chronicled in detail in my dad’s hospital-stay records.

“Family meetings,” which included my father, consisted of hospital-team members directing questions not to me, but to him, a man who either couldn’t understand or hear what was being said — and culminated when I was presented with the ultimatum that he would be discharged, and either I took him home, found him another place to live, or paid several hundred dollars a day to keep him there.

To punctuate the point, I was given a room with a phone and a directory to call retirement homes for availability.

I found one in Ottawa’s west-end suburb of Kanata, run by Chartwell Retirement Residences, whose own problematic issues regarding care for its residents were recently chronicled in The Tyee.

My father spent some respite time at that property before permanently moving to another Chartwell residence, also in Kanata, with the look of a warm country-style chalet. The staff was friendly; the meals were hearty; the place was clean; and my dad even got a girlfriend. He couldn’t thank me enough for finding the place.

But after a while, most of the convivial crew left, replaced by a front-office seemingly more interested in the corporate bottom-line than in the well-being of residents.

Time with my dad became more working visit than social call as I found myself having to strip his bed and clean the sheets somehow overlooked by the outside personal support worker assigned to provide my father with daily care. I came to realize that caregiving and advocacy requires the duty to act rather than haggle over the failure of someone doing their job.

Still, while patience is a virtue for the ones you love, it has its limits when your loved ones are being exploited.

The final insult was dealt my dad when he ended up at Saint-Vincent Hospital as his health deteriorated. The move became necessary when Chartwell reassessed his care needs and determined that he would have to pay at least $2,500 more per month for services that his regular nurse told me the home would not be able to provide.

A final slap to me was when I set out to clear his room on the Saturday of the Victoria Day long weekend two years ago. Since I ran out of room for his belongings in my car, I asked if I could return the following day to get the rest — and when I did, my dad’s belongings were already placed in storage. The toilet in his room had been ripped out and painting had begun in preparation for the next resident.

My dad spent over a year at Saint-Vincent’s. The independence he enjoyed at Chartwell was over. He spent most of his days outside of his room in the corridor watching people come and go.

Gone was his walker, and my father was confined to a wheelchair, which he would foot-propel up and down the corridor.

On one occasion, after saying my goodbyes to him, which always included a mutual exchange of “I love you,” he followed me to the elevator — and this time, entered it with me. I was off to an appointment; he wanted to come with me — and be outside to feel the sun and fresh air on his face.

It was tough to ride that elevator with him back to his floor. My pa could not be left unsupervised. He was in a hospital.

But at least he never ended up living in a long-term care during the pandemic.

“If you can get your relatives out of seniors’ homes, try to do so as fast as you can,” stated the headline to an April 2 article in the Globe and Mail by its veteran health reporter Andre Picard.

How right he has proven to be.

Even after the virus recedes, for thousands of families there will remain the difficult road towards placing a relative in a nursing home. We must so thoroughly reform our elder care system that the road is smoothed and clearly marked and safe and secure for all who try to navigate it.

As Erin Beaudoin, a Nanaimo nursing home CEO aptly says in another Tyee piece today, “We don’t want to make nursing homes the hell you move into before you die.... It should be pleasant. We owe them that at least.”

In the days leading to my dad’s death, he — and I, by extension — were offered quiet dignity by a diligent medical staff at Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital.

The battleground of past wars waged had fallen silent.

My pa and I had come to the end of a long journey. For a hardworking and loving man, it was difficult to see him suffer. It was hard, as well, to let him go. He was my best friend, my father, my muse.

Despite his descent into dementia, my father never forgot who I was, and he was still discussing plans for us right up until his last moments.

With Pavarotti playing in the background and sitting upright in his bed, my dad looked directly at me with wide blue eyes and said his final word to me — “what” — more as statement than question.

What comes next in how we treat our elders will define who we can be. ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: