A little over a century ago, south of Lougheed Mall and west of Koreatown in suburban Burnaby, a boxcar full of Japanese railway workers was washed off its tracks. Twenty-three were killed, 15 badly injured.

Called the Great Northern Railway Disaster and also the Japanese Workmen Railway Disaster, the incident isn’t a well-known part of local history.

But for its 110th anniversary the City of Burnaby and Japanese-Canadian advocates are hoping to bring new attention to the story, and what it says about the danger and discrimination faced by immigrant workers in the early years of British Columbia.

The disaster happened during a days-long rainstorm, called the “worst in years” by the Vancouver World.

It caused “raging floods” that wrecked local rail lines, in late November 1909. Four-and-a-half inches of rain were recorded in a 24-hour period.

In the midst of this storm, the Great Northern Railway Co. required track repairs in Aldergrove. The railway was based in the U.S. but had lines in B.C. and the Yukon.

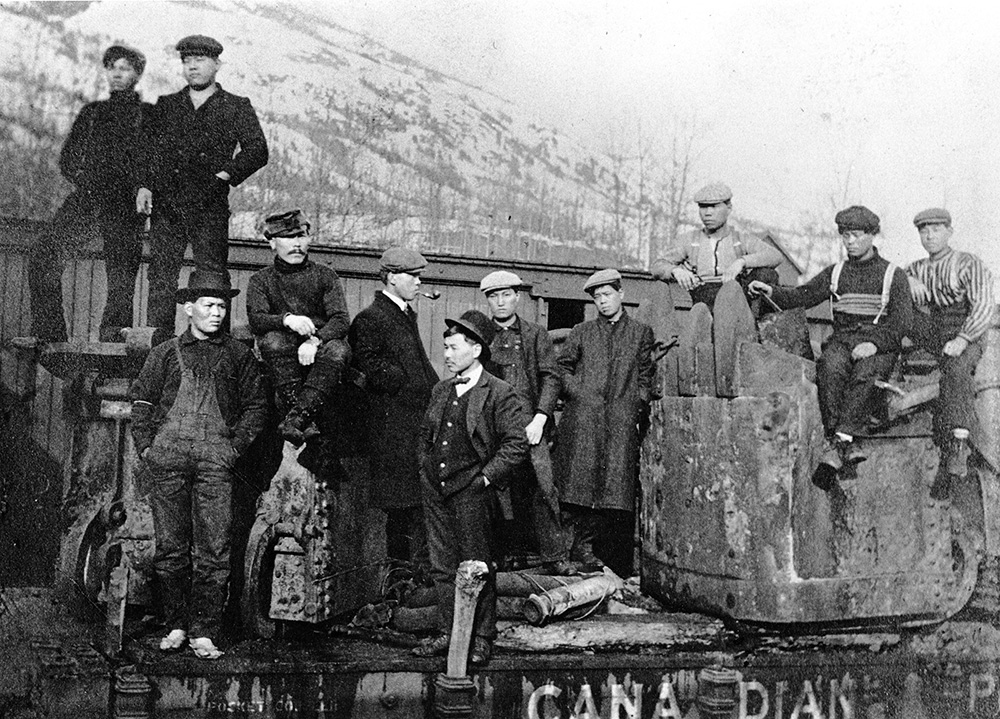

The company hired a Japanese crew to do the repairs, despite a provincial law that forbade railways from hiring Asian workers. (This was essentially anti-immigration policy; B.C. figured that if there was no work for Asians, then they wouldn’t want to immigrate.)

Anti-Asian discrimination was prevalent at the time, with Vancouver’s race riots taking place just two years before in September 1907. Japanese Canadians were stereotyped as spies, due to the growing might of Imperial Japan.

Some railways, like Great Northern, didn’t care about the law because they could pay Asian workers cheaply. So they would hire them quietly, hiding work crews on quiet stretches of track.

The rainstorm showed no signs of stopping on Nov. 29. At 5:30 a.m., a small work train carrying the repair crew departed Vancouver for Aldergrove.

White workers rode in the locomotive and the caboose, while the Japanese workers sat or slept huddled in an unheated boxcar.

They were hired by a foreman named K. Katsuda.

“This was a common practice with workers from Asia,” said Lisa Codd, a heritage planner at the City of Burnaby. “There was a labour boss — a foreman — and the company would pay that person, and then they would pay their crew. They had to have good English language skills.”

The work train passed Burnaby, which was mostly rural, nowhere near as urban as growing Vancouver.

One of Burnaby’s many ravines, Kilby Creek — known as Lost Creek today because it disappears for a section beneath Lougheed Mall — was culverted to support the railway crossing.

But due to the downpour, the culvert burst.

Around 6 a.m., when the train carrying the work crew came to the crossing, the tracks and the ground beneath washed away, and the train plunged into the ravine.

After the boxcar fell, the flatcar travelling behind it followed, slicing through the boxcar — killing and injuring the Japanese workers.

The white workers riding in the locomotive and the caboose were able to jump to safety.

Because the work train had encountered the washed-out culvert so early in the day it saved a passenger train from Seattle, called the Owl, from meeting the same fate.

Another crew of Japanese workers was hired to clean up the wreckage. They were paid double the going rate due to the difficult and gruesome conditions documented by the newspapers of the day, which did not hold back on descriptions of gore. (We’ll spare you the worst passages.)

Groups of “morbid sightseers” visited the scene later that day in spite of the pouring rain, a newspaper reported, “gazing [on] the mangled bodies which lay beside the track awaiting removal to the undertakers.”

The dead men had their eyes, noses and mouths “stopped up with sand and dirt,” the paper said.

Codd points out how the Province newspaper covered the story. Two headlines appeared in the same-size type: “Score of Japanese met death in wreck” and “One white man badly injured. He was George W. Kemp.”

“His full name is in there, and he survived,” noted Codd. “Yet there are 23 unidentified Japanese.”

Coverage like this dehumanizes the immigrant workers who were hired for dangerous jobs.

“So often our history is devoid of stories of racialized people,” said Lorene Oikawa, the president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians. “We’re in 2019, and we don’t see enough markers, so we don’t understand the diversity that was there.”

Some recent research heralds Burnaby’s “super-diversity,” making it seem like a new phenomenon, but Codd said this ignores the diverse place that Burnaby was in the early 20th century.

The city has a rich history of immigrant labour. Aside from Japanese, early Burnaby was home to Chinese and Sikh and Muslim South Asians, many of whom were employed in lumber by the Burrard Inlet.

“Folks that get low pay for dangerous work, they look for other ways to earn money through self-employment,” said Codd.

Farming was one way. Another was collecting tree stumps left behind by loggers and selling them to shingle mills; landowners didn’t mind as it helped clear their land.

And of course, there were the jobs with railways.

“We think of Canadian railway history as being more Chinese-related than Japanese,” said Tomoaki Fujimura, 43, an avalanche technician who has interests in avalanche history and early Japanese Canadians.

One of Fujimura’s research projects was on the 1910 Rogers Pass avalanche, which killed 32 Japanese railway workers. He was able to track down five families of descendants, many of whom cried upon hearing this history.

As for the 1909 disaster, Fujimura was able to find a Japanese newspaper that included the names of the dead in its coverage.

But “sometimes newspaper articles can’t be trusted,” he said. Fujimura went to Mountain View Cemetery in south Vancouver where the dead were said to have been buried.

There, he found graves for 19 of the 23 dead men, most with Buddhist burials but a few with Christian.

As for the 15 injured survivors, the Great Northern Railway Co. asked them to resume track repairs a few days after the disaster. They refused.

An inquest was held in New Westminster a week after the incident, where railway officials admitted the boxcar was not designed for safety and that the engine’s headlight was faulty. It was also revealed that the culvert was already reinforced with crossbars, and yet did not hold during the storm.

In the end, the jury decided that no one could be blamed due to the unexpected nature of the storm.

You can find a plaque created by the BC Labour Heritage Centre marking the location of the disaster on Burnaby’s Central Valley Greenway, about 1.2 kilometres east of the Cariboo Place entry, at the spot where Lost Creek flows into the Brunette River.

“It’s a reminder,” said Codd, “of the precarious place that migrant workers still have in our communities.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: