You won’t fully understand Vancouver politics if you’re only looking at the old left-right divide. As housing and issues around urban life become central to political debates, the traditional labels don’t go deep enough.

Old issues — like a living wage — offered a clear left-right divide. Progressive candidates supported the idea; conservative candidates did not.

But as we saw in last year’s municipal election, some “progressive” candidates fought to block increased development in neighbourhoods, while others urged changes to allow increased density. Nominally conservative candidates were divided on density and other urban issues.

It’s been three months since Vancouverites elected 10 councillors (and a mayor) of mixed political leanings out of a record-setting 71 council candidates.

There have been some surprising agreements and divisions so far — and no implosion yet. The mixed council unanimously supported left-leaning COPE Coun. Jean Swanson’s motion aimed at protecting tenants from renovictions and aggressive buyouts.

But NPA councillors — the Non-Partisan Association is the city’s longtime right-leaning party — were split when left-leaning OneCity Coun. Christine Boyle proposed that the city study the creation of a new land-value capture tax. The NPA was divided again on duplexes: Coun. Colleen Hardwick wanted to rollback a previous motion that allowed duplexes citywide, but her fellows did not.

Two municipal observers have been trying to make sense of the smorgasbord of stances on urban growth that have been splitting the left and the right: Ian Bushfield, host of the Cambie Report municipal affairs podcast, and political scientist Stewart Prest, who teaches at Simon Fraser University and Langara College.

For half a year, they’ve been tinkering with a new axis that goes beyond the traditional left and right: urbanists on one end and conservationists on the other. Urbanists want policies that encourage density and more multi-modal transportation options (walking, biking, public transit) in pursuit of affordability, while conservationists are more cautious about urban growth.

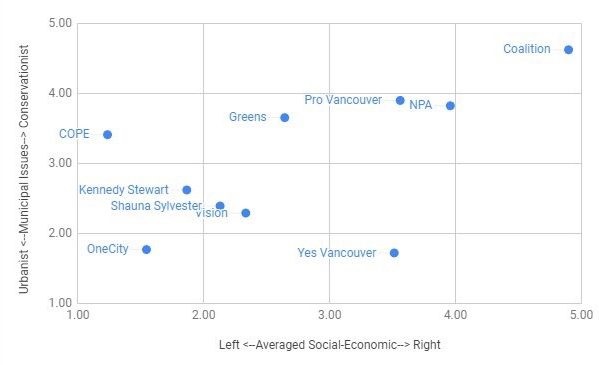

It looks like this:

It’s similar to the multi-axis political compass, which measures authoritarian-libertarian leaning in addition to the economic left-right.

(Though even with two axes, politics can be tricky to measure. For example, a council candidate who ran last election, Rohana Rezel, called the urbanist-conservationist axis “lazy and meaningless” because a term like urbanist may not capture differences like adding market versus non-market homes. He added that contributors who placed his party ProVancouver right of centre may not have read their platform, which emphasized working class interests and providing them housing.)*

Bushfield and Prest will be presenting a paper on their urbanist-conservationist axis at the annual Canadian Political Science Association meeting in Vancouver this June.

Here’s our exchange with Bushfield and Prest on how the frame helps us understand the evolving politics in a city desperate for housing solutions. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

The Tyee: What were you hoping to answer with a new political axis? How did you come up with it?

Prest: I was just trying to find a frame that would allow me to explain such a crazy election.

The left-right spectrum seemed to dominate Vancouver politics in previous electoral cycles, but wasn’t as much help in helping voters (and parties) orient themselves around what was shaping up to be the dominant question of the campaign — should the city change to meet the rapidly worsening housing situation?

Bushfield: I came across the multi-axis political compass, which tries to separate social issues from economic ones, while in undergrad.

It helps explain people who differ from traditional stances, like those who support same-sex marriage but want to see lower taxes.

But that compass alone didn’t explain what was happening in Vancouver politics.

Prest: We decided on the urbanist-conservationist axis when we noticed that parties and candidates on both sides of that traditional left-right divide were advocating “lots of change” or “little or no change” — though their reasons for taking one position or the other were often quite different.

Bushfield: For example, the NPA is traditionally the “right-wing” or free market party, but Hector Bremner upset that by challenging the party’s approach to preserving traditional single-family zoning across the city and ended up starting his own party.

So our goal was to try and explain these differences on urban change in a way that would ultimately be helpful to politics followers and voters.

How did you decide which party or candidate belongs where?

Bushfield: We crowdsourced the public (though not a random sample in any way) from Cambie Report listeners, our hyper-engaged Patreon supporters and Twitter followers to plot major parties and mayoral candidates on various axes — economic issues, social issues and what we called urbanism versus conservatism.

Most of the parties fell along a traditional left-right spectrum on economic and social issues, so the political compass wasn’t that useful. But this meant that we could plot the urbanist axis against the traditional left-right axis.

The results were unsurprising, as the widely discussed “urbanist” parties of Yes and OneCity were in their respective right and left-wing corners, while Wai Young’s Coalition Vancouver was off in the far conservationist/right-wing corner. Vision and independent mayoral candidates Kennedy Stewart and Shauna Sylvester all clumped together in about the middle of the chart (albeit slightly to the left politically). The Greens and COPE were both a bit tougher for people to place, with both being placed on the conservationist side, although there was some spread in where people placed those parties.

Prest: Ian’s crowdsourced graph does a pretty excellent job of answering this question in my opinion. Some parties the crowd could map easily, like Coalition. Others were harder for contributors to place, like ProVancouver. That in itself was interesting to see.

Other surveys supported the findings. For example, Tom Davidoff from UBC’s business school also found “urbanist” candidates had much in common despite differing on the left-right spectrum — though they still differed on the kinds of solutions they preferred.

So with this new lens to understand parties and candidates, how does it explain the election results and the council today?

Prest: The most obvious, I think, is the NPA crackup. If we think back to the start of 2018, this election seemed like the NPA’s to lose, and yet by the time June arrived, the party had fragmented in spectacular fashion, producing not one but two offshoot parties. While I’m sure personality and internal party dynamics played a role, there were fundamentally different positions within the party on housing, and it proved impossible to paper over the gaps. The result was the urbanist Yes Vancouver led by Hector Bremner on the one hand, Wai Young’s conservationist Coalition Vancouver on the other, and Ken Sim’s NPA somewhere in between. Yes Vancouver and Coalition both failed to get significant traction, but given how close the race between Sim and Kennedy was, it’s quite possible that NPA crackup changed the outcome of the race for mayor.

The framework can also help us understand how different parties can agree on the problem, while still disagree on the solution, as I alluded to above. For instance, Yes Vancouver focused on market-based solutions, while OneCity favoured things like new taxes to capture a portion of land value increases. Though both are urbanist parties, they differ significantly in terms of what policies would be best in responding to the housing crisis.

Another example is the Vancouver Green Party. At times the party seems to operate as two factions. On one side, you have Adriane Carr, who has long been cautious about the prospect of additional development in the city. On the other, you have Pete Fry, who clearly is more urbanist. Clearly, it’s possible to share some commitments, while differing significantly on urbanist-conservationist issues.

Bushfield: I agree. The only thing I’ll add is that the frame helps us see how Vision Vancouver seemed to make an effort to run their campaign differently. I think there was a clear effort to try to court urbanist voters who worried the party hadn’t moved fast enough on things like densifying the city or expanding transit. So in the lead up to the election, we saw the duplex motion, a much more urbanist-friendly slate and pledges to support SkyTrain to UBC. Ultimately, I think other factors played a role in Vision’s demise, but the party’s change in rhetoric suggests they were attuned to these broader conversations.

You mentioned that the left and right camps were once pretty clear cut in Vancouver. What is it now that’s causing them to split over this issue of change?

Bushfield: One of the terms we’re starting to hear a lot is “spatial justice,” particularly from left-wing urbanists. I think this is best encapsulated in OneCity’s campaign motto of “every neighbourhood for everyone.” The challenge is that words are easy and the political reality of building temporary modular homes in Marpole or other wealthier neighbourhoods is tough.

The other major schism is what urbanists see as the market’s role in housing. On the left, there’s a deep skepticism over the market’s ability to deliver affordable housing, [and] a lot of concern over speculation and empty homes. These parties would rather see the government get more involved in the provision of social and other affordable housing.

Meanwhile, the urbanist right is hoping a “get-the-government-out-of-the-way” approach through relaxed zoning will result in significant new construction that will bring prices and rents down over time. Of course, a drop in housing values will take a huge hit out of a lot of homeowners’ equity, so you see skepticism of that policy among others on the right (notably NPA supporters).

Prest: Housing is such a tricky issue because it affects and divides people in the city in a way few other issues do. Homeowners benefit financially from high housing prices. Renters do not. And yet you find renters and owners on both sides of the political spectrum.

On the left, you hear suspicions regarding the role of developers and the effects of new development on existing renters. On the right, you hear skepticism regarding changes to zoning and neighbourhood character — you can get to similar conservationist positions through very different reasoning.

Also, I think the new restrictions on municipal campaign financing made it easier for candidates and parties to strike out in new directions. In previous cycles, when the major parties had a huge advantage in fundraising, I think we would have seen less of that experimentation.

You mentioned “spatial justice.” It’s interesting that this kind of “progressive” language about inclusivity is used by urbanists on the left and urbanists on the more market-oriented right. What do you make of this? What does it mean to be “progressive” when it comes to housing?

Prest: I think some of that may be the opportunistic use of popular language, which can run the risk of watering down terms. At the same time I think urbanist parties, regardless of political orientation, all are responding to the sense that the city has become exclusionary in the sense that many can no longer afford to live or buy property here. That shared sense naturally lends itself to use of words like “inclusive.” Given how much they differ in terms of solutions however, it does render such words perhaps a bit less meaningful than previously.

Bushfield: It was fascinating to me that nearly everyone in Vancouver’s election labelled themselves as “progressive” at one point or another. I think that, and the references to spatial justice, point to the overall centre-left lean of Vancouver’s electorate.

The development community, on the other hand, has a clear material interest in many of the stated YIMBY (yes in my backyard) goals of relaxed zoning laws and increased density. Someone’s going to have to build all of those new condos.

Have you seen urbanist-conservationist divides elsewhere in the region? Or outside of Metro Vancouver?

Bushfield: I think it played a defining role on the North Shore, where critics of recent developments ultimately won out over those who’d been championing greater density.

Prest: In some other centres the effect is less clear-cut — perhaps in part because the left-right spectrum itself is less well developed. In Surrey, for instance, parties often form around a particular mayoral candidate, such as Dianne Watts’ Surrey First coalition or Doug McCallum’s governing Safe Surrey Coalition, rather than a unifying ideological commitment. We may see that start to change though as the municipalities throughout the region continue to grow quickly, and housing, transit, and related issues continue to push municipal politics into the spotlight.

Looking to the future of Vancouver politics, do you think a gap between the urbanists and conservationists will widen over time?

Bushfield: Despite all of the hype over the housing supply-focused, YIMBY wave, it really didn’t come crashing in on election night. I don’t think that’s talked about enough. The most pro-YIMBY party was Bremner’s Yes Vancouver (it’s got “yes” right there in the name) but he placed fifth, about 2,000 votes behind Wai Young.

And across the region, whenever candidates ran with a focus on density, they lost.

At the same time, many longtime political watchers noted with interest that this was one of the first elections where rezoning the entire city was even up for debate. The advocates for such changes aren’t likely to disappear, particularly as the city goes into the process to draw up a city plan.

Personally, I think this is good for the city and our politics. Given the depth of the housing and affordability crisis, people are looking for bold ideas and solutions. And given the historic injustices upon which this city is built — from settlers building on unceded territories to racist zoning policies to demolishing Hogan’s Alley and more — I’m hopeful we can move forward toward the spatial justice that those leftist urbanists talk about.

Prest: Some of this story is yet to be written. It’s too soon to say whether this election was a one-off in response to particular circumstances or the start of a new more diverse era of political parties. Circumstances may continue to change, like if the issue of municipal electoral reform bubbles up again.

However, it is clear that housing and transit issues aren’t going away anytime soon, so parties are going to have to continue to position themselves accordingly. The finance rules seem like they’re here to stay, so candidates will have opportunities to chart their own course if they disagree with what the more established parties are doing. That undoubtedly will keep things interesting.

* Story updated on Jan. 29, 2019 at 2:50 p.m. to include a council candidate’s comment about where his party was plotted on the urbanist-conservationist axis. ![]()

Read more: Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: