If you’ve voted in a federal or provincial election, you’re familiar with first-past-the-post. The winner-takes-all system is used across Canada — and in many other former British colonies.

It’s simple.

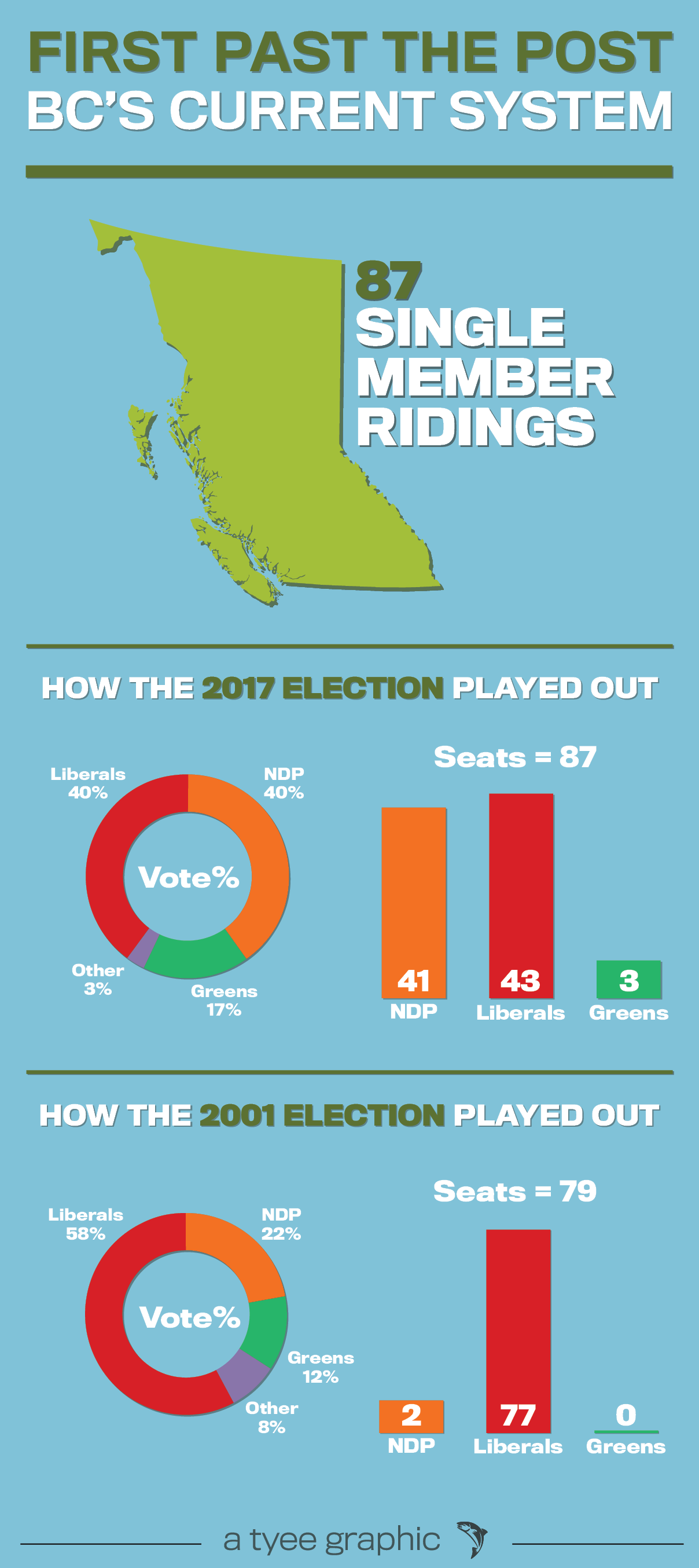

In B.C., the province is divided into 87 ridings. The candidate in each riding who gets the most votes is elected.

If one party wins more than 50 per cent of those ridings, it forms a majority government. If not, it can form a minority government or make a deal with another party to form a coalition. Either way, it will need support to pass legislation.

That simplicity is a selling point for defenders of the current system.

“You can explain it in less than 20 seconds,” said Bill Tieleman, president of the No BC Proportional Representation Society. “First-past-the-post has provided a successful, stable and simple electoral system.”

Tieleman and other “No” campaigners also argue FPTP often produces stable majority governments and ensures every MLA is elected by voters in a geographic region.

Proportional representation is used by more countries, though Tieleman points out that countries like India, the U.K., the United States and Pakistan all use FPTP. The Coalition Avenir Quebec won a majority government with only 37 per cent of the vote in Quebec’s provincial election on Oct. 1.

But advocates for change say the current system delivers total power to a party often supported by 40 per cent — or less — of voters, and that women and minority groups are under-represented under FPTP.

Antony Hodgson, president of Vote PR BC, says countries that use proportional representation demonstrate the benefits.

“Pro Rep delivers improved satisfaction with democracy, improved representation of women and minorities, [and] incredibly strong economic performance,” he says. “It’s correlated with increased growth in the GDP, decreased government debt and improved environmental performance. It accomplishes these things by bringing more voices into the legislative conversation.”

In a proportional system, unless a party won a majority of votes, it would have to enter a coalition with other parties to form government. This means parties will have to work together and reach compromises to enact legislation.

Tieleman says minority or coalition governments are less likely to have the ability to enact policies that might be unpopular in the short term but bring lasting benefits. He points to the creation of ICBC and the Agricultural Land Reserve by the NDP majority after the 1972 election. The party captured less than 40 per cent of the popular vote.

It’s true that FPTP tends to elect more stable governments, though that might be changing. In B.C. and New Brunswick, the most recent elections resulted in what were considered fragile coalition governments.

And proportional representation, because it can require compromise and collaboration between parties, tends to produce more stable policies and avoids lurches to the right or left after elections.

“Countries using Pro Rep end up with public policies that address a much broader range of interests in society and that allows those societies to improve more rapidly,” said Hodgson.

“I think people don’t appreciate just how successful Pro Rep has been in improving democracies around the world.”

Hodgson cited two B.C. examples of election results many consider to be unfair: the 1996 wrong-winner election in which the NDP lost the popular vote but won a majority of seats, and the massive over-representation after the 2001 election, when the Liberals won 97 per cent of the seats with 57 per cent of the vote.

Tieleman argues other changes could improve our democracy without changing electoral systems. “You could enact legislative rules that the budget requires 60- or 65-per-cent approval and that would force the government to win opposition support in order to get the budget passed,” he notes. “You could do that tomorrow.”

However, it’s not clear if a party in government would make that change, which would drastically reduce its power.

Tieleman also proposes mandatory voting.

The urban-rural divide

In the 2017 election, the BC Liberals took 20 of 24 seats in the Interior and northern B.C. The result raised concerns that the region would not have a real voice in the NDP government.

Hodgson said this kind of result can lead to regional conflict and alienation. A new party — the BC Rural Party — has emerged since the election.

Proportional representation would ensure MLAs from different parties represent rural ridings, giving them a voice in government, Hodgson says.

Tieleman maintains that proportional representation would encourage parties to focus on the Lower Mainland, where around half of British Columbians live.

But all three proportional representation systems on the ballot have measures to prevent this from happening.

Tieleman also argues the current first-past-the-post system can increase diversity in the legislature.

“The Chinese-Canadian community, Indo-Canadian community and, to a more limited degree, the Indigenous community, when there’s a significant proportional population from those communities, they have an excellent chance of electing a member from one of the political parties,” said Tieleman.

Proponents of proportional representation point out that it offers a chance to increase diversity even when minority communities are concentrated in a single riding. For example, if Indigenous voters across the province supported the same party, it would likely win a few seats in the legislature. This is currently much harder, because Indigenous people account for only a small minority of the population in most areas.

The opponents of proportional representation — the BC Liberals and the No BC Proportional Representation Society — argue that under the new system “your MLAs will get chosen from a list of party insiders.”

That’s not true. Under two of the proposed systems, a minority of MLAs would be regional representatives elected from party lists to ensure proportional representation. But it hasn’t been determined whether voters would choose candidates for the list, or the party.

And every voter would still have a local representative elected through FPTP.

Advocates for the current system are encouraging voters not to respond to the second question on the ballot, which asks which proportional representation system they would prefer.

There is not enough information, says Tieleman. “Voters should have the right to see the whole entire process, riding boundaries, details, everything else, and then vote on it.” ![]()

Read more: Politics, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: